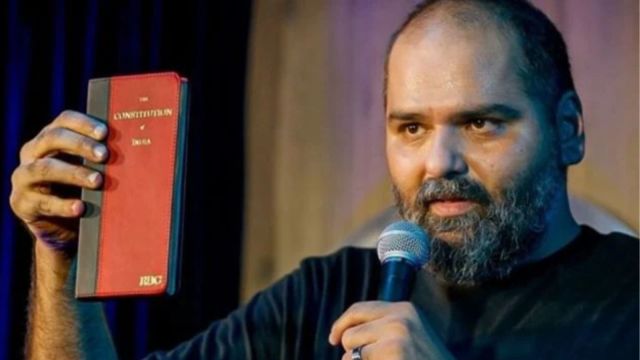

The recent vandalising of Habitat studio in Mumbai by Shiv Sena workers where artist and activist Kunal Kamra performed his stand-up special, Naya Bharat, needs attention in a wider context: The cultural politics of humour. Against the Zero FIR filed in Mumbai, the Madras High Court rightly granted inter-state anticipatory bail to Kamra. Humour and critical creative expressions are integral to a functional society. Humour amounts to a cultural politics that rejuvenates social relationships.

Kamra, who has been at the centre of various controversies over the last half decade, serves as a reminder of the fundamentals of cultural politics. He is not the only humouris who has allegedly hurt sentiments while trying to tickle audiences. Others like Vir Das and Samay Raina have also found themselves in controversies. Many amateur humour artists in an engineering classroom lament the decline in the sense of humour in contemporary India. There is a need to return to a moment in the country’s civilisational history that will help us understand the love and hate for humour artists.

Sometime between 200 BCE to 200 CE the ancient sage Bharat had prepared his treatise the Natyashastra on rasas (emotions) for anubhav (experience) and abhinaya (enactment). Legend has it that the classical Sanskrit text useful for the performing arts, dance and drama was but it ran into trouble, when the first cohort of disciples began to utilise its lessons.

Allegedly, they performed satirical acts mocking sages who were doing penance. Agitated, the sages began to complain about the Natyashastra’s status as the “fifth Veda:. This was perhaps an announcement of the fact that the humourists will be subversive. They will challenge puritanical mindsets and low thresholds of tolerance.

Philosophical engagement with humour in Ancient Greece was similar. Aristotle agreed with his teacher Plato that wit and humour are essential tools in debate. But they were also ambiguous about the scornful humour that may derail intellectual seriousness. Plato is quoted as saying, “No composer of comedy, iambic or lyric verse shall be permitted to hold any citizen up to laughter, by word or gesture, with passion or otherwise”. Such paradoxical approaches to humour are common in modern classics as well.

No wonder, then, that the fear of subversion has made humour a social, cultural and political suspect. But it appears that humor can also be a permissible cultural expression. As a result, the epics, classical dramas, and folklore are fraught with subversive humour. Had there been no humour, there would have been no clowns and jesters, witty court men, and performers across cultures. While many may object to Kunal Kamra due to his subversive humour, yet many others may be willing to accept him as a mascot of cultural politics in contemporary India.

Literary critic Terry Eagleton has appropriately documented the historical trajectory of intolerance in his book, Humor. Steering clear of the paradoxes around the intellectual and political engagement with humor, Eagleton helps us understand why we “must” laugh. Like the child in the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale who laughed at the vain emperor, a society must be able to laugh for diverse reasons — performing psychoanalytic and social functions. The child god Krishna is no less a subversive humourist in front of his guardian mother Yashoda as in critical engagement with the emperor Kamsa and his atrocities.

The lesson here is clear: Humour will be, essentially, politically incorrect. Incongruity is integral to humour — it plays a double function in society. In a broader sense of cultural politics, humour may reaffirm a social order while posing a challenge to stagnant and monolithic ways of thinking.

The writer is associate dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and teaches humour to the engineering students at South Asian University