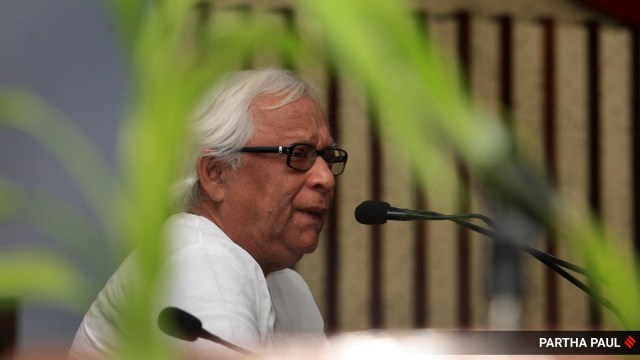

Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee died on the morning of August 8 (Thursday). Bhattacharjee was born in North Calcutta on March 1, 1944. He was suffering from Chronic Pulmonary Obstructive Disease (COPD) for several years. Bhattacharjee was in politics during a tumultuous period in the late 1960s and early 1970s before becoming a young minister of Information and Public Relations in the first Left Front government from 1977 to 1982, led by Jyoti Basu.

After completing his undergraduate Honours degree in Bengali, he became more active in the Communist Party of India (Marxist). He became a member of the CPM in 1966. Due to his active role in the youth movement in the late 1960s in the context of the anti-Vietnam war protests and later during what the communists termed as the “semi-fascist regime” of Siddhartha Shankar Ray from 1972-1977, he could not finish his Masters in Bengali. An avid lover of world literature, Bhattacharjee was an essayist, playwright, a regular contributor to organisational literature as an intellectual, and a translator of eminent figures of world literature. He was mentored by the hardliner Pramod Dasgupta.

As a political personality, Bhattacharjee was emotional too. He abruptly left the state cabinet in the 1990s, accusing the Jyoti Basu ministry of being one of “thugs and thieves” (choreder montrishobha). It was a time when the urban lumpen proletariat and lumpen capital were growing in Kolkata and nearby areas as a fallout of de-industrialisation. These sections were increasingly used by Bhadrolok politicians to meet partisan interests.

Bhattacharjee lived an austere life. Like many veteran communists, he was thoroughly opposed to any dealings with corrupt elements within the party. The push for corporate-led industrialisation became a part of the Left government’s agenda after it won a tough assembly election in 2001. Bhattacharjee became the chief minister, and was welcomed by the middle class and urban rich. They saw him as a figure who could break the economic stagnation in the state and bring back industrial growth, which had suffered from periodic flights of capital and militant trade unionism. But he also confused the Bhadrolok class by renaming Calcutta as Kolkata. It seemed to hint that cultural revivalism could stand in for substantive demands and issues for wages, health, education, and public infrastructure.

During Bhattacharjee’s time, the CPM slogans of “Krishi amader bhitti, shilpo amader bhobishyot” (agriculture is our base and industry is our future) and “bamfront shorkarer bikolpo ekti unnototoro bamfront” (the alternative to Left Front is a better Left Front) became the rallying cry for the Left in the 2006 and 2011 assembly elections. In 2006, the Left Front saw major vote share increases among the urban middle and upper classes and a noticeable decline in rural votes, compared to the 2001 election.

After the 2006 victory, Bhattacharjee was accused of being arrogant. When the Singur protests led by the then-opposition Trinamool Congress gathered steam, Bhattacharjee asserted, “We are 235, and they are 30, what will they do?”, referring to his government’s legislative majority.

During the pandemic in January 2022, the Government of India bestowed Bhattacharjee with the Padma Bhushan. He politely declined the honour, in keeping with many Left stalwarts before him.

Bhattacharjee presented a contrast to the Western-educated, worldly Jyoti Basu. Perhaps his more rooted background was a reason he did not see through many of the gambits of elites, in politics and beyond. He may have missed how and why so many of India’s most powerful ganged up against him during his last term as CM.

In 1971, the year of the Bangladesh Liberation War and when Bhattacharjee and his comrades were firebrand activists, Seemabaddha (Company Limited), a film by Satyajit Ray, was released. It is about a foreign manufacturing firm, the upper echelons of its management and their upper-class lives. The film had one magnificent dialogue against cigarette smoking and apprehension about banning cigarettes. I wish Bhattacharjee, a heavy smoker, had learned from the film the perils of his habit as well as dealing with Big Capital.

The writer is a political scientist at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata