Mukarram Jah passes away: A brief history of the Nizam’s massive inheritance, and its rapid loss

Mir Osman Ali Khan had left behind 104 grandchildren, so Mukarram Jah was no stranger to court battles over property and money. However, one such battle involved a sum of £35 million, the governments of India and Pakistan, and was eventually settled by a UK court. Here is the story.

The mortal remains of Mukarram Jah, the titular eighth Nizam of Hyderabad, will be kept at Hyderabad’s Chowmahalla palace on Tuesday (January 17) for the public to pay respects.

Nawab Mir Barket Ali Khan Walashan Mukarram Jah Bahadur passed away in Istanbul at 89.

Osman Ali Khan had left behind 104 grandchildren, so Mukarram Jah was no stranger to court battles over property and inheritance. However, one such battle involved a sum of £35 million, the governments of India and Pakistan, and was eventually settled by a UK court.

Here is the story of this court battle, called the Hyderabad funds case, and of the eighth Nizam himself.

The Hyderabad funds case

On September 20, 1948, a day after Hyderabad’s forces had surrendered to India, the Nizam’s finance minister, Moin Nawaz Jung, transferred a sum of £1,007,490 and nine shillings to the account of Pakistan’s High Commissioner, Habib Ibrahim Rahimtoola, without first taking the Nizam’s consent. This money lay in the National Westminster Bank in London.

In 1954, India sued for the return of the money, but the case was stayed, with Pakistan claiming sovereign immunity. The bank then said it would keep the money until the Nizam, the government of India, and the government of Pakistan decided among themselves who it belonged to.

In 2013, Pakistan broke sovereign immunity itself, by going back to court for the sum, which by now, accumulating interest, had increased by 35 times. The legal battle went on for six years, with Pakistan claiming that the money was sent because the Nizam wanted Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, to procure weapons for them to fight off Indian troops. These weapons were bought and dropped off to Hyderabad by a British pilot, Frederick Sidney Cotton, in 35 trips from Karachi, claimed Pakistan, and thus, the money was payment for services rendered.

In 2018, the government of India and the Nizam’s grandsons – Mukarram Jah and brother Mufakkam Jah – decided to fight the case jointly. A year later, in 2019, the UK High Court ruled in favour of India and the Nizam’s heirs, granting them the entire £35 million.

Experts have pointed out that for India and Pakistan, the case was about much more than money. Several times in the 70 years that it took to resolve the case, there had been attempts to settle it out of court, but the ties between the two nations made that impossible.

In his 2017 book ‘The People Next Door’, T C A Raghavan, who was posted in the High Commission at Islamabad twice, first as Deputy High Commissioner and later as High Commissioner, wrote about the case, “For Pakistan, the issue is of Hyderabad’s forced accession following a military intervention when its ruling Muslim prince wanted independence and a closer relationship with Pakistan. The fund thus represents that symbolic relationship… For India, equally, the issue is of principle — what possible claim can Pakistan have to the funds of the erstwhile Hyderabad state?”

For Mukarram Jah, the case could have meant many things, but the finacial aspect could not have been insignificant, as his estate haemorrhaged money and his expenses developed sinkholes, from his sheep farm in Australia to his many divorces and alimony payments.

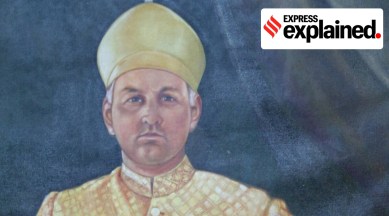

A brief history of Mukarram Jah

Mukarram Jah was born on October 6, 1933 in France, to Prince Azam Jah and Princess Durru Shehvar, the imperial princess of the Ottoman Empire. He was educated in the Doon School in Dehradun and later at Harrow and Peterhouse, Cambridge. He also studied at the London School of Economics and at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

On April 6, 1967, he was coronated as Asaf Jah the Eighth, after the death of Mir Osman Ali Khan in February 1967.

Chosen as heir over his father Azam Jah, Mukarram did not show much interest in managing and preserving his vast estate. According to a 2007 article in The Guardian by historian William Dalrymple, upon accession, Mukarram inherited a “ridiculously inflated” army of 14,718 staff and dependants, including people whose only job was to dust chandeliers or to ground the Nizam’s walnuts; a staggering collection of gems and jewellery; and heirlooms that included priceless paintings and furniture.

He also inherited a vicious financial wrangle, with far too many competing claims and legal cases on the various properties. Barely six years later, Mukarram fled to a sheep farm in Australia, leaving the estate and his headaches in the hands of deputies and devoting his own time to the great love of his life – tinkering with old automobiles.

However, things went from bad to worse, as Mukarram was swindled by those he trusted and jewellery and heirlooms pilfered. The sheep farm had to be sold off to settle his debts, and the Nizam then moved to Turkey.

In the 2000s, matters improved somewhat, with the Nizam’s first wife, Princess Esra, returning to Hyderabad and introducing some order into the mess there. Two of the Nizam’s palaces, Chowmahalla and Falaknuma, have since been restored, and the latter is now run by the Taj Group.

However, family tiffs and troubles never ended for the Nizam. Even in the Hyderabad funds case, after the UK high court order, some of his cousins claimed that as Mukarram was merely the titular Nizam, he could not be considered the heir to the sum deposited by the seventh and actual Nizam, and that money should be distributed among all the descendants.