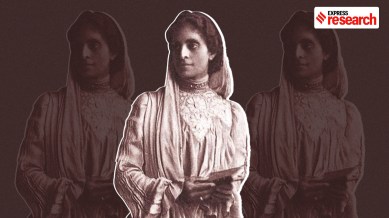

“I am to read law: the desire of my heart is accomplished,” an excited student wrote home in the 1890s. The student was Cornelia Sorabji, and what made the accomplishment truly remarkable was that she was the first Indian woman to study law and the first woman to study law at Oxford.

At the age of 22, Cornelia embarked on a remarkable journey. On September 19, 1889, she left for England to study at Somerville College, Oxford, at a time when higher education for women was still a rare and celebrated achievement. She expressed her hopes and determination in a letter home, cited by British historian and Cornelia’s nephew Richard Sorabji in his work Opening Doors: The Untold Story Of Cornelia Sorabji: “‘How I do hope all will be successful.’”

This is the story of Cornelia Sorabji’s resilience and determination to become India’s first woman lawyer with an Oxford degree.

Cornelia’s early life

The Sorabji family’s early years were spent in Nashik, Maharashtra, where their father taught his six daughters and one son history, English, and mathematics. The family embraced an English way of life, with the older sisters taking on the role of governesses for the younger ones. The family’s intellectual environment was rich, but it was also one that would soon face the limitations of societal expectations.

In time, the Sorabjis moved to Pune where Cornelia’s mother Francina became a pioneer in social service. She founded several schools for underprivileged children and later provided teacher training, working tirelessly through times of crisis, including famine and plague.

While the two eldest Sorabji daughters were denied entry to the University of Bombay because of their gender, Cornelia became the first woman to matriculate there at just 16. She went on to attend Deccan College in Poona, which was affiliated with the University of Bombay.

Story continues below this ad

At Deccan, she was the sole female student among 300 male peers. Richard Sorabji’s account reveals the hostility Cornelia faced—her classmates would slam classroom doors and keep her out of lectures. Despite these challenges, she thrived, becoming one of only four students to earn first-class honours in 1887, and ultimately emerging as the top student at Deccan College.

With her stellar academic record, Cornelia hoped to win a prestigious Government of India scholarship to pursue further studies in England. However, her application was rejected solely because of her gender. Undeterred, Cornelia took up a position teaching English Literature at Gujarat College in Ahmedabad. Meanwhile, she reached out to influential women in Bombay and Poona, including the legendary Florence Nightingale, hoping to secure support for her Oxford ambition. Her efforts paid off. Before long, Cornelia was on a 35-day journey from India to England.

On September 19, 1889, Cornelia arrived in England. After meeting her sponsor, Lady Hobhouse, in London, she made her way to Oxford a month later—her journey, though just beginning, marked the start of a historic path.

Cornelia Sorabji’s legal career

Cornelia began her studies at Somerville College, Oxford, on October 15, 1889. Initially reading English literature in her first term, she switched to law in her second. During her time at Oxford, she also took the opportunity to visit the House of Commons several times, where she listened to debates from the ladies’ gallery.

Story continues below this ad

A rare story, as recounted by Richard, involves Cornelia hosting a Christmas party in December 1890 for a few close friends at Oxford. During the event, she introduced the Indian saree as a decor piece and encouraged her friends to try draping it, though with an English blouse worn underneath.

In 1892, Cornelia became the first Indian woman to pass the Bachelor of Civil Laws (BCL) exams. However, due to prevailing gender restrictions, women were not allowed to register as advocates, and she was denied her degree. It wasn’t until 1922, when women were finally permitted to collect degrees, that Cornelia was able to receive her long-awaited qualification. Reflecting on the achievement, she remarked, “I am only third class, and this is a frightful disappointment… They say I ought to be proud of it and all the rest. But I am conceited enough to feel it.”

The 1890s were a struggle for Cornelia as she tried to navigate the British imperial system, which excluded women from practicing law. Returning to India in 1894, she embarked on a decade-long campaign to secure legal opportunities for women. In 1903, Cornelia testified before India’s Secretary of State in London, advocating for the creation of “a new profession for women,” according to historian Antoinette Burton in Dwelling in the Archive: Women Writing House, Home and History in Late Colonial India.

That same year, a question about the condition of Indian women in the Court of Wards was raised in the House of Commons, which led to Cornelia’s groundbreaking appointment in 1904 as “Lady Assistant to the Court of Wards of Bengal and Eastern Bengal and Assam.” This role, primarily focused on legal matters for widowed women and their children, was significant, as the Indian Civil Service had largely been dominated by Britons.

Story continues below this ad

After retiring in 1922, Cornelia moved to London, where the English bar had recently been opened to women. There, she qualified as a barrister and returned to India in 1924 as the country’s first female barrister.

Beyond law

Cornelia Sorabji dedicated her life to two interconnected causes: improving the conditions of purdahnashin women—those secluded from society, typically from high-caste or upper-class Hindu and Muslim backgrounds—and raising awareness of their plight among reform-minded audiences in both Britain and India. According to Cornelia, the greatest threats to these secluded women were the relatives who sought to seize their estates and the priests who controlled their lives. She was outspoken about both, advocating for these women’s rights in a society that largely ignored them.

As Burton notes, “While Sorabji gained much attention in her lifetime as a pioneering woman lawyer, she should also be remembered as the first Indian woman to be salaried as a native informant for the Government of India.” In the colonial context, knowledge was as vital to imperial control as tax collection. From 1904 to 1922, Cornelia became an active participant in this colonial system of knowledge. Her expertise was so valued that, according to Richard Sorabji, “her enormous knowledge of India” was crucial during the tumultuous years of 1939-1945, when she consulted on Indian affairs with the Secretary of State for India, Lord L S Amery.

Through her annual reports on her work with the Court of Wards, Cornelia helped standardise information about ‘native’ women. These reports, spanning nearly two decades, provided a detailed, statistical account of the lives of purdahnashin women, framed within the colonial discourse of modernity. Burton further explains that “Such statistics were intimately tied to her own career ambitions and her desire for financial security; part of the reason for detailing the scope of her work was to advocate for a better salary, more travel funds, and, above all, a government pension upon her retirement.”

Story continues below this ad

Cornelia’s British connect

By the time World War II began, Cornelia Sorabji was still in collaboration with the British Secretary of State for India. Her remarkable career involved interactions with seven Viceroys and connections to high-ranking officials, including King George V and Queen Mary. The reasons behind her steadfast support for British rule remain somewhat enigmatic. Scholars and writers have suggested that her loyalty may have stemmed from the favourable treatment she received from the late Victorians, who valued her expertise and contributions.

Cornelia passed away in 1957 at the age of 87, leaving behind a profound mark on India’s legal and social landscape. Her story has been meticulously explored by author Suparna Gooptu in her 2010 publication Cornelia Sorabji: India’s Pioneer Woman Lawyer: A Biography, which offers a nuanced view of Cornelia’s complex legacy. Gooptu avoids simplistic labels like “feminist” or “imperialist” and instead embraces the idea that history is made up of individuals who cannot be confined to stereotypes. Cornelia Sorabji is one of them.