Shiva and Madonna: How 19th-century textile weavers threaded a story of co-existence

A new textile section within New Delhi’s Crafts Museum stitches together folk craft marked by modern influences of business, politics and culture

This is the Hooghly of the 19th century, the rupee of the British Raj floating down midstream along with the fish the waters were rich in, a metaphor for the city of Kolkata that became the seat of colonial power and its riches. There is the barge carrying officials of the Raj as common people go about their activities on the banks. And somewhere, a Shiva temple co-exists with a Madonna icon, symbolising the syncretism brought in by foreign cultures. This is not a painting but the oldest kantha mural from over 200 years ago that is on display at Textile Gallery 2, National Crafts Museum.

This newly-opened section is a curated showcase from a pool of the existing 2,600-piece museum collection of textile art that threads how folk traditions not only transformed and evolved over centuries, adapting to regional variations, incorporating modern influences but became an unending spool of visual history of its time. Much like Instagram reels. “Everybody talks about history. But this tells stories as seen through the eyes of our weavers and craftsmen, who documented and interpreted the world around them,” says Sunil Sethi, the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI) chief, who curated this with art historian Dr Jyotindra Jain. For eight months, they looked at not just weaves but embellishments like embroidery, Kalamkari, brocade, block prints and resist-dyed fabrics.

“I chose the kantha piece near the entrance because it is a testament of how the simple running stitch was upcycled from something as utilitarian as piecing together old pieces of cloth as a child’s swaddle to being a social commentary of its times. This piece has motifs of playing cards everywhere, swirling between sahibs and memsahibs, chandeliers and medallions of Queen Victoria. It is a subtle comment on how the East India Company gambled away the fortunes and inheritance of native people. The kantha is also an artform that has survived over thousand years from the pre-Vedic times,” says Sethi.

Restoration was a big ask. A team of textile conservators identified the damage on these fabric relics, lined them with chemical-free cotton or voile. They used seasoned pine wood as well as a backing of Tyvek, a breathable, waterproof and dust proof material, to avoid possible condensation. They used vacuum cleaners, distilled water cleansing and even got in women from Bikaner, who are skilled in preservation techniques.

Co-curator and art historian Dr Jyotindra Jain had seen how most museums are focussed on the authenticity of the past. “But we needed contemporaneity, something that could inspire current design students as well. And yet what we call tradition has actually been dynamic. For example, the way weavers and embroiderers incorporated Mughal motifs, the way the kantha thread changed from cotton to silk with the Portuguese influence, how our ikat grew out of Southeast Asian traditions courtesy the maritime route, and how the Baluchari weaver did an elaborate threaded pallu of a buggy horse and carriage, capturing their socio-economic-cultural milieu,” says Dr Jain.

If the kantha emerged to meet the journalling needs of ordinary women, so did the phulkari. One of the exhibits is an elaborate depiction of a community of women who documented the journey of a girl from birth to her marriage. “The sari collection speaks of this continuous transition. Beyond the warp and the weft, the border and pallu have always had hand-inserted elements, be it as an applique, embroidery, weaving or printing technique. That’s why the sari is the weaver’s laboratory of innovation,” says Jain.

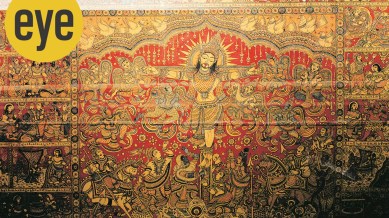

The show stealer panels at the museum are those of Kalamkari art. Contrasting the Ramayana and Mahabharata panels are those depicting the life of Jesus Christ and a good versus evil parable from Iran. What’s interesting is the differing styles. While the crucifixion of Christ has him as the central deity, the other events concerning his disciples have them wearing Indian clothes and looking Indian. In contrast the swirling serpent head on the Persian scroll looks influenced by Chinese scroll paintings. About 18ft long, the kalamkari spreads on Ramayana and Mahabharata are a series of hand-drawn story blocks , dyed in vegetable colours with a summary in Telugu script written beneath each block. “Each piece here is the result of the assimilative process of culture,” adds Dr Jain.

So the dyes moved down centuries from indigo and yellow to industrial dyes that brought in a new aesthetic. “What surprised me was that the creators were not rigid about rules and kept changing them. Although they stuck to some motifs and symbols because they were familiar and skilled in using them, they innovated on design, techniques and colour scheme. And they did that on their own as none of these works of art were commissioned or had royal patronage,” says Sethi.

The zari panel of small squares, depicting different weaving techniques with no repetition, is a masterclass on a single fabric. The Raidana block print panel has more than 1,000 hand-made patterns, far more intricate and refined than machine-printing. And if our modern designers are creating new weaves, the textile museum has an undated old fabric made of peacock feather filaments and bound by zari.

Meanwhile, on a museum tour are a group of fashion students from Chennai. They go past the innovation studio by designer Payal Jain, where mannequins are dressed in bridal gowns, made from leftover pieces of fabric and buttons. Wearing traditional saris over T-shirts, these girls embody the museum’s new aesthetic possibilities.