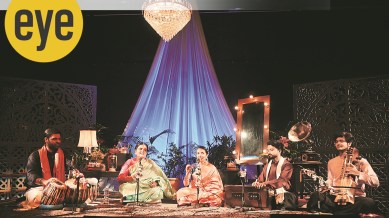

Avanti Patel and Rutuja Lad’s ‘O Gaanewali’ Reclaims the Legacy of Courtesans and Women Singers

The show is a nod to courtesans who navigated patriarchy and asserted their cultural authority

Looking back through history, the term ‘gaanewali’ has never just meant ‘a woman who sings’. The label has always been taken away from its literal moorings and loaded with a certain moral suspicion for women performers who have been given other names such as tawaifs, baijis and nautch girls among others. This was despite them being master artistes, whose contribution to the subcontinent’s cultural landscape remains invaluable. “People associated the term with sex work and prostitution. That’s what Bollywood also showed us often,” says Mumbai-based 30-year-old Hindustani classical vocalist Avanti Patel.

Patel, who is training under the tutelage of Jaipur-Atrauli gharana exponent Ashwini Bhide-Deshpande, wanted to reclaim what the term ‘gaanewali’ literally meant — a woman who sings — and strip it of the disrespect that it was associated with. So, she decided to name her show ‘O Gaanewali’, which will be showcased this week at three different venues in the National Capital Region, including at The Piano Man (October 26) and Stein Auditorium (October 25). In June this year, the two also launched an EP with six pieces from their presentation.

“The whole point was to take the negative power away from the term,” says Patel, who’s been a student of sociology and anthropology, who received flak for the title of her show from within the music community as well. Even her alma mater, Mumbai’s St Xavier’s College, had concerns with the name. “Gaanewali and naachnewali were insults back in the day. But for us the title was a conscious decision,” says Patel. She wanted to treat these as songs of triumph, of artistic brilliance and as an ode to women musicians whose cultural erasure remains problematic.

She roped in singer Rujuta Lad, also a student of Bhide-Deshpande, to sing these songs with her. That both Patel and Lad were interested in thumri, dadra and ghazals — the semi-classical forms that have often had many women performers at their helm — helped build the project. Lad had also spent 12 years learning from the noted Jaipur-Atrauli gharana exponent Dhondutai Kulkarni, who passed away in 2015 (Namita Devidayal’s The Music Room details her life). Both Patel and Lad grew up in Mumbai and also knew each other through inter-school music competitions.

As for the project ‘O Gaanewali’, the whole thing was not particularly planned. It began with a proposal Patel wrote during Covid-19 for a grant from Harkat Studios — a boutique arts studio based in Mumbai — “completely on a whim”. Once she got the grant, the two mounted their first show — a virtual presentation — in 2021. Their live debut was in 2022. Patel and Lad soon realised that they could not pull it off on their own and needed a director to bring in coherence and emotional depth. “Even if I have a knack for writing or narrating, that does not make me a theatreperson or an actor. I had to get people on board to help us see that through and translate what we wanted to say,” says Patel, who then brought in theatre artistes Mallika Singh and Meghana AT to help them weave together music and spoken word.

Then there was the research in terms of poring over the books that have been written on the subject, including Saba Dewan’s Tawaifnama (2019) and her documentary The Other Song (2009), which captured the world of courtesans. They referenced work done by Hindustani classical vocalist Shubha Mudgal and tabla exponent Aneesh Pradhan besides what they had imbibed — thumris and stories — from Bhide-Deshpande, whose aunt, the well-known vocalist Sarla Bhide, also learned from thumri doyenne Shobha Gurtu.

“We must acknowledge the privileged space that we come from. As young musicians of today, performing in itself is not as difficult as it was 100 years ago. Our reverence for the women performers comes from awareness. These women musicians carved their way through a lot of struggle and because they struggled, in many ways we don’t have to,” says Lad, about yesteryear courtesans. These singers had once wielded a lot of power and wealth until the Anti-Nautch Movement of the early 20th century, which, supported by the British and Indian social reformers, stripped them off livelihood and cultural expression.

Musically, the two have tried to pack many thumris: songs of love, separation and longing, chaitis, kajris, dadras and several ghazals into the hour-and-a-half show — from Gauhar Jaan’s Aan baan jiya mein laagi and Chha rahi kaali ghata made popular by Begum Akhtar; Rangi saari gulaabi chunariya which has, perhaps, belonged more to Gurtu than anyone else; Shubha Joshi’s Ja bairi ja badra to Mirza Ghalib’s Muddat hui hai, often featured in Pakistani ghazal queen Iqbal Bano’s concerts.

Another thing that Patel wanted was to make sure that everyone on the stage, including the accompanying artistes, spoke about their art and instruments. Mainly because the stigma was not just associated with courtesans, it was eventually attached to the concept of thumri, even sarangi, which accompanied the music of the courtesans. “Even Shobha Gurtu, who was a trained vocalist, from the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana, wasn’t taken seriously by many because she chose to sing thumri. The sarangi’s downfall… it’s all part of a larger historical story that we are trying to present through the show,” says Patel.