The Maratha quota demand in Maharashtra, explained

Chief Minister Eknath Shinde has been able to persuade Maratha activist Manoj Jarange-Patil to halt his agitation for now. But the vexed, decades-old Maratha quota issue presents no easy solutions.

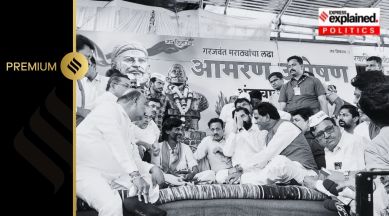

Maratha activist Manoj Jarange-Patil on Thursday broke his 17-day fast demanding reservation for the community in jobs and education after Chief Minister Eknath Shinde visited him at Antarwali Sarati village of Jalna district and asked for a month’s time to look into the issue. The demand for a Maratha quota is likely to gain momentum as Lok Sabha and Assembly elections approach.

Who are the Marathas?

Historically identified as a “warrior” caste, the Marathas comprise mainly peasant and landowning groups who make up almost a third of the population of Maharashtra. Most Marathas speak Marathi, though not all Marathi-speaking people are Marathas.

The Marathas have been the politically dominant community in Maharashtra — since the formation of the state in 1960, 12 of its 20 Chief Ministers, including Shinde, have been Marathas. The division of holdings and problems in the farm sector over the years have, however, led to a decline in the prosperity of middle- and lower middle-class Marathas.

Since when have the Marathas been demanding reservations?

The demand for Maratha reservation has been a political issue and reason for mass protests in the state ever since Mathadi Labour Union leader Annasaheb Patil led the first protest rally in Mumbai in 1981. During 2016-18, the Maratha Kranti Morcha (MKM) held massive statewide demonstrations — while the first phase of 58 rallies remained peaceful, the second phase of protests saw bloodshed and several alleged suicides.

Over the years, a succession of Maratha Chief Ministers have been unable to satisfy the community’s demands. In the latest phase of the agitation, Jarange-Patil began a hunger strike on August 29.

What has triggered the current phase of agitation?

The Marathas want to be identified as Kunbis, which would entitle them to benefits under the quota for Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The demand for OBC reservation arose after the Supreme Court, in May 2021, struck down the quota for Marathas under the state’s Socially and Educationally Backward Class (SEBC) Act, 2018.

In June 2019, the Bombay High Court upheld the Maratha quota under the SEBC Act. However, the court ruled that the 16% quota under the Act was not “justifiable”, and reduced it to 12% in education and 13% in government jobs, as recommended by the State Backward Class Commission.

The HC also said that total reservations should not exceed 50%, except in exceptional circumstances and extraordinary situations. This would be subject to availability of quantifiable and contemporaneous data reflecting backwardness, inadequacy of representation and without affecting the efficiency in administration.

What happened in the Supreme Court?

In May 2021, a five-judge Constitution Bench headed by Justice Ashok Bhushan struck down the provisions of the Maharashtra law providing reservation to the Maratha community, which took the total quota in the state beyond the 50% ceiling set by the court in its 1992 Indra Sawhney (Mandal) judgment.

In November 2022, after the SC upheld the Centre’s 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS), the Maharashtra government said that until the issue of Maratha reservation is resolved, the poor among the Marathas could not benefit from the EWS quota. In April this year, the court turned down Maharashtra’s plea for a review of its decision, following which the state said it would file a curative petition.

The government also said that a commission would be set up to carry out a detailed survey of the “backwardness” of the community.

What is the state’s position on the current agitation?

On September 1, police used batons and tear gas as they clashed with protesters. More than 40 people, including both protesters and policemen were injured. The clashes led to massive mobilisation in support of Jarange-Patil’s fast, and there were very large protests and bandh calls in Kolhapur, Pune, Solapur, Yavatmal, Dhule, Buldhana, Nashik, and Amravati.

The protests put the state government on the defensive. Deputy CM Devendra Fadnavis apologised for the police action, and the government presented Jarange-Patil with copies of a Government Resolution (GR) based on a Cabinet decision of September 7 to issue Kunbi caste certificates to certain members of the Maratha community, and an older GR from 2004 promising reservation to eligible Maratha-Kunbis and Kunbi-Marathas.

However, Jarange-Patil was not pacified; he said the new GR did not accept his demands, and that the 2004 GR was yet to be implemented. He ended his fast after Chief Minister Shinde visited him and asked for time to look into the legal complexities involved.

How have OBC organisations reacted to the Maratha demand?

OBC organisations have come together to vehemently oppose the Maratha demand. OBC Jan Morcha president Prakash Shendge has threatened to launch a statewide agitation if the government gives the Marathas OBC reservation.

OBC leaders say they are not against Marathas getting reservation, but it should not be at their cost. OBCs already get only 19% reservation in Maharashtra compared to the 27% nationally, and cannot be expected to share the quota with the politically and numerically dominant Marathas, they say.

The 52% reservation in the state is currently divided into Scheduled Castes 13%, Scheduled Tribes 7%, OBCs 19%, Special Backward Classes 2%, Vimukta Jati 3%, Nomadic tribe (B) 2.5%, Nomadic Tribe (C) Dhangar 3.5%, and Nomadic tribe (D) Vanjari 2%.

Separately, there is a 10% EWS quota which is applicable to the non-quota section of the population irrespective of caste and religion, with an annual income limit of Rs 8 lakh.

How is politics in the state impacted by the Maratha reservation issue?

The Marathas’ demand for quota within the OBC category has created a sharp Maratha-OBC polarisation. Marathas have traditionally been closer to the Congress and NCP, while BJP and Shiv Sena have banked on the OBCs.

However, political equations have changed in the last one year. The Sena and NCP have split, and the BJP has teamed up with the Shinde faction of the Sena and the Ajit Pawar faction of the NCP. The picture is much more complicated now.