Why the Red Fort became the venue for the PM’s Independence Day speech

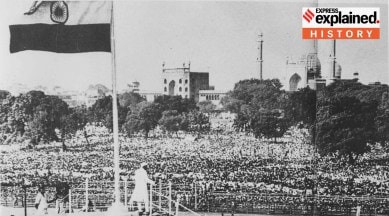

Every year on August 15, the Prime Minister of India hoists the tricolour and addresses the nation from Delhi’s historic Red Fort. Why was Red Fort chosen for this honour?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi hoisted the tricolour and addressed the nation from the Red Fort in Delhi, early morning on August 15, on the occasion of India’s 77th Independence Day.

Jawaharlal Nehru first started the tradition in 1947, although his address was on August 16, a day after the official handover of power. In his speech, he memorably called himself the pratham sevak of India.

Over the years, the Red Fort has become an integral part of India’s Independence Day celebrations, often capturing the mood of the nation and the government in power.

But why was Red For chosen for this honour? To understand this, first a brief history of how Delhi became the seat of power in India.

‘Capital of Hindustan’

It was under the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1506) that Delhi became a major capital city from where a large part of north India was ruled.

Babur (1483-1530), the founder of the Mughal dynasty, was the first to refer to Delhi as the ‘capital of all Hindustan’ in the 16th century. Though the Mughals, under Akbar (1542-1605) shifted their capital to Agra for some time, they continued to be seen as the rulers of Delhi.

Finally, under Shah Jahan (1592-1666), Delhi became the Mughal capital once again with the establishment of Shahjahanabad in 1648 (what we know today as Old Delhi). The Mughals would continue to rule from the fortified citadel of Shahjahanabad – more popularly known as the Red Fort – till 1857. Even as their power waned, they continued to be recognised as the symbolic rulers of India, in part due to their association with Delhi.

“Not only did the Mughal territories shrink, the Mughal emperor became increasingly ineffectual even within them,” historian Swapna Liddle wrote for The Indian Express in 2021. “Yet, such was his [the Mughal emperor’s] symbolic significance as the source of legitimate sovereign authority that many of these new states, including a newcomer, the East India Company, continued to rule in his name, and to issue coins in his name until well into the 19th century,” she added.

Perhaps the best example of this was the Rebellion of 1857. After mutinying, the rebels immediately headed to Delhi and declared the aged Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775-1862) as their king.

Delhi at the time was of minor importance to the East India Company, and housed very few Europeans. But for the rebels, it was still the strongest symbol of indigenous authority, around which they rallied and the fall of Delhi pretty much sealed the fate of the rebellion.

The stamping of British imperial authority over the Red Fort

After capturing Delhi from the rebels, the British initially planned to raze the whole city (Shahjahanabad) to the ground, their primary objective being to wipe out the memory of the Mughal Empire from the city. And destroy they did, razing beautiful Mughal buildings such as the Akbarabadi mosque near Daryaganj or the bustling Urdu Bazaar near Chandni Chowk.

Although they stopped short of completely razing the Red Fort to the ground, the British stripped it of all its imperial majesty. Precious artworks and the imperial treasury (what was left of it in 1857) were looted, and many of its inner structures were demolished to be replaced by British structures.

As per estimates, as much as 80 per cent of the Red Fort’s original inner structures were destroyed, replaced by British buildings to house their troops and service their needs. The palace was converted into a British garrison and the famed Diwan-i-Aam into a hospital.

The Red Fort we see today, thus bears the undeniable stamp of British imperial authority, as much as it stands as a relic of the Mughal Empire’s grandeur.

Co-opting Delhi’s symbolic authority

In the years following 1857, the British systematically relegated Delhi to a minor provincial town.

At the same time, the city still remained a potent symbol of authority in India, something the British also tapped into, notably with the Delhi Durbars (1877, 1903, 1911). These grand ceremonies proclaimed the British monarch as the Emperor of India, and invited rulers from Princely States across the subcontinent to Delhi to pay their tributes to the British Crown.

The British finally decided to shift their capital to Delhi from Calcutta in 1911, building a grand new city which would be completed in 1930.

Suoro D Joardar, professor at the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi, noted in his article ‘New Delhi: Imperial Capital to Capital of World’s Largest Democracy’ (2006) that besides the centrality and connectivity of Delhi, it also “carried in the minds of the colonial rulers a symbolic value – as the old saying goes: ‘he who rules Delhi rules India’ – a realisation of the Indian ethos, especially across northern and central India, enhanced during royal contact with the innumerable minor and major princes.”

Reclaiming the Red Fort, reclaiming India

The Red Fort would return to the forefront of public consciousness in the years prior to Independence.

Under Subhas Chandra Bose, the Indian National Army – comprising Indian PoWs captured by Japan and civilian volunteers – raced towards India from the Burmese border in 1943, aiding the Japanese war effort. This effort would eventually fail – Bose died in a plane crash and between 1945 and 1946, senior officers were tried for treason.

These highly public trials were held at the Red Fort. Causing an outpouring of sympathy for the INA and upping nationalist sentiments against the British, the trials firmly established the Red Fort as a symbol of power and resistance in the minds of the Indian public.

It is in this context that Nehru’s decision to hoist the flag over the Red Fort in 1947 makes sense.

As Swapna Liddle wrote in 2021: “With the coming of Independence, it was necessary that the site of the Red Fort, over which the British colonial government had sought to inscribe its power and might, be symbolically reclaimed for the Indian people.” Each year, our Independence Day celebrations emphasise this reclamation.