Bharat Ratna for L K Advani: How his Rath Yatra contributed to the rise of the BJP

Advani’s Rath Yatra led to communal tensions in many parts of the country, but also catalysed the rise of the BJP as a national political force. His contribution to the BJP’s present-day stature is undeniable.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced on Saturday (February 3) that veteran BJP leader L K Advani will be conferred with the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian honour.

“I am very happy to share that Shri LK Advani Ji will be conferred the Bharat Ratna… One of the most respected statesmen of our times, his contribution to the development of India is monumental,” PM Modi posted on X.

Advani, 96, was instrumental in transforming the Bharatiya Janata Party into a national political force in the late 1980s and early 1990s. His 1990 Rath Yatra was taken out to to mobilise volunteers for the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, and was central to the party’s rise. A quick recall.

From Gandhian Socialism to Hindutva

The BJP emerged in 1980 following the dissolution of the Janata Party. In its first national conference, held in Mumbai that year, party president Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s address underscored that the BJP was not simply a new incarnation of Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Rather, Vajpayee claimed the legacy of Jayprakash Narayan, and declared Gandhian Socialism to be the party’s foundational ideology.

“Vajpayee’s decision to chart a middle path was most likely based on a strategic calculation intended to retain supporters of the erstwhile Janata Party that had joined the BJP,” political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot wrote (‘Refining the Moderation Thesis’, 2013).

But this position did not reap rewards in the 1984 general elections. The Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress won over 400 seats on the back of a sympathy wave after Indira Gandhi’s assassination. The BJP won only two. This failure, however, was pivotal for the BJP’s eventual rise. Advani took over the party’s reins, and guided it towards a new direction.

Cashing in on the Ram Janmabhoomi Movement

In the 1980s, Hindu nationalist organisations such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) upped the ante on the Ram temple issue. While the earliest proposal to build a Ram temple in Ayodhya came up in the 19th century, the 1980s saw the movement gather momentum.

The BJP, under Vajpayee, had been somewhat sceptical about openly wading into the matter. But Advani sensed that the growing Ram temple agitation offered a unique opportunity to consolidate the Hindu vote. In 1989, the party officially took on the Ram Janmabhoomi cause in its historic Palampur Resolution. With Advani also stepping up pressure on Rajiv Gandhi over his (mis) handling of Sri Lanka and Kashmir, as well as the Bofors scandal, the BJP quickly emerged as a potent political force.

In the 1989 general elections the BJP won 85 seats. But Advani sensed that even greater inroads could be made — and needed to be made. In 1990, V P Singh decided to grant OBC reservations for government jobs, accepting the Mandal Commissions recommendations. This, Advani felt, could seriously undermine the BJP’s Hindutva. Thus, he took to the road, with the intention to create pan-Hindu pressure to construct a Ram temple on the Babri Masjid site.

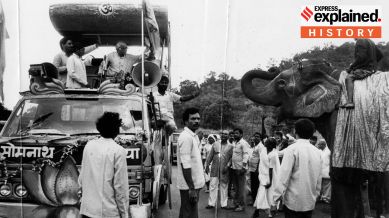

The Rath Yatra

On September 25, 1990, L K Advani commenced his Rath Yatra from Somnath, Gujarat. He planned to traverse across the country on a rath (a chariot, or in Advani’s case, a modified Toyota made to look like a chariot), building momentum for the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, and ultimately arriving at Ayodhya to stake claim to the Babri Masjid site.

Thronged by thousands of ‘activists’, Advani’s procession was marked by songs and slogans, all with a singular aim to galvanise pan-Hindu support for the temple. As historian Ramachandra Guha noted, “the imagery of the yatra was religious, allusive, militant, masculine, and anti-Muslim.” (India After Gandhi, 2007).

As he travelled through the country, Advani’s Yatra left a trail of violence in its wake. Communal violence intensified especially after Advani’s arrest in Bihar, on the orders of Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav. “Hindu mobs attacked Muslim localities, and — in a manner reminiscent of the grisly Partition massacres — stopped trains to pull out and kill those who were recognizably Muslim,” Guha wrote.

Historian K N Panikkar wrote that between September 1 and November 20, when the Yatra took place, a total of 166 “communal incidents” took place, killing 564 people. (‘Religious Symbols and Political Mobilization: The Agitation for a Mandir at Ayodhya’, 1993). Uttar Pradesh, where 224 people were killed, saw the worst of the violence.

Despite this, the Rath Yatra was a raging success for Advani and the BJP. In the 1991 elections, the BJP emerged, after the Congress (244 seats), as the second largest party in the Parliament, raising its tally to 120 seats. It also formed the government in Uttar Pradesh.

“Clearly, the Ram campaign was paying political dividends. Riots were being effectively translated into votes,” Guha wrote.

The Babri demolition and after

On December 6, 1992, around 100,000 kar sevaks descended upon the Babri Masjid and razed it to the ground. Advani too was in Ayodhya that day, but was not prepared for what had happened. He would later say that the events of December 6 “bothered him”.

A wave of communal violence would once again sweep through the country, and although Advani did not condone the mosque’s demolition, his party nonetheless reaped the benefits of it. Over the course of the 1990s, the BJP strengthened its national presence on the back of its role in the Ram Janmabhoomi temple, with Atal Bihari Vajpayee taking oath as the prime minister three separate times.

Advani gave way to Vajpayee in the aftermath of the Babri demolition, to allow the party to be helmed by a more “moderate” face. He would never be able to meet his prime ministerial aspirations. Nonetheless, his role in the rise of the BJP to its current, seemingly infallible position, remains undeniable.