The fabric that connected East to West and wove the myth of the Silk Road

The Silk Road is one of the most important trade routes in world history, predicated on the trade of silk between China and Rome. Its legacy spans continents and centuries, bringing together empires, religions, technology and philosophy.

The history of the world is inextricably linked to the history of trade, in particular, the widespread trade of goods obtained on the back of atrocities and those capable of shaping our entire monetary system. In Tracking the Trade Winds, we look at the seismic importance of gold, sugar, silk, oil and more in connecting civilisations, enriching empires and facilitating the migration of people and resources.

When one thinks of global trade over the centuries, the first thing that comes to mind is probably the most famous trade route in world history. The route that connected the East to the West, bringing soft, smooth and strong fabric along with it. The route that spanned civilisations, disseminated religious beliefs and interwoven ideas — the nervous system of our Atlas, the Holy Grail of trade routes, the Silk Road.

Despite the enduring and romanticised popularity of the Silk Road, most scholars today debate the use, origins, and application of the term. So what was the Silk Road and why did one item, that could neither be consumed nor ignited, dominate its characterisation?

Origins of Silk

Many myths exist about the origin of silk. The accounts of the great Chinese philosopher Confucius state that around 3000 BCE, a silk worm’s cocoon fell into the teacup of the Chinese Empress Leizu and, wishing to remove it, she began slowly pulling at it. As she pulled, the cocoon unravelled into long fibrous threads, which, according to legend, the Empress decided to keep and weave into her clothing. Thereafter Empress Leizu has been celebrated in China as the goddess of silk.

The earliest evidence of silk, however, predates Confucius’ account. Silk fibres have been found in Neolithic sites in Jiahu and Henan from 8,500 years ago. The earliest surviving evidence of silk fabric dates back to 3630 BC with archaeologists speculating that it was used in the burial ceremony of a young child in China.

In its early days, the right to wear silk was reserved only for the Emperor and his highest noblemen. It was perceived as a sign of great wealth and stature due to its shimmering appearance created by the fibres’ ability to refract light. Over time, its usage spread to other segments of Chinese society but still remained largely a product for the uppermost echelons of society.

The first instance of silk fabric being discovered outside of China was in Egypt around 1070 BCE. Given that silk production was a highly guarded secret, this also points to the earliest forms of trade between China and the Middle East. During the time of the Roman Empire, silk was already a highly prized trading commodity, with Roman leaders even going as far as to ban the wearing of silk in order to halt the vast amounts of gold leaving Rome for China.

The immorality of silk was underlined by prominent Roman historians like Seneca the Younger, who lamented that silk failed to hide a woman’s decency to the extent that “I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one’s decency, can be called clothes … Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife’s body.”

However, silk remained greatly valuable and it was only a matter of time before its cultivation spread to other ancient civilisations. Sericulture, or the process of cultivating silkworms to produce silk, spread to Korea around 200 BCE, India by 140 BCE, Japan by 300 CE, and the Byzantine and Arab civilisations around 550 CE.

Sericulture’s growth led to a decline in the significance of Chinese silk exports, although they continued to dominate the market for luxury silk. Western Europe had access to silk manufacturing due to the Crusades, particularly the Italian states, which dominated production. The European Middle Ages saw the beginning of technological advancements in manufacturing, with innovations like the spinning wheel making their first appearance in the 11th century.

The silk business in Europe was greatly altered by the Industrial Revolution. Innovations in cotton spinning made it considerably more affordable to produce, resulting in cotton production becoming the primary focus for many businesses. Production of silk fell throughout the 15th century due to an outbreak of several silkworm illnesses, particularly in France, where the industry never fully recovered.

For all its value as a trading commodity, silk’s greatest legacy may however be derived from the route it forged across Eurasia. Connecting East to West, the Silk Road was considered the most important land route in the history of the pre-modern world.

History of the Silk Road

The route came into existence under the Han dynasty of China in the second century BCE when Wudi, Emperor of the Chinese Han dynasty, became the first leader to successfully expand westwards through the vast Central Asian steppe. China and Rome became the terminal points of this road, which also connected the great civilisations of Eurasia and later Europe.

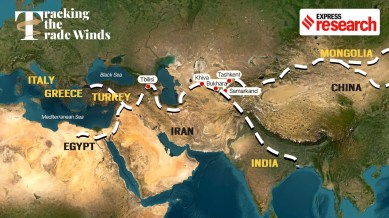

The journey commenced in Chang’an (now Xian), where the Silk Road’s first tendrils unravelled. Central Asian cities like Samarkand and Bukhara emerged as pivotal crossroads along the route, serving as bustling hubs where diverse cultures converged and trade flourished. As it ventured southward, it encountered the Indian subcontinent, where cities like Taxila and Peshawar, in modern-day Pakistan, became nodes of commerce and cultural exchange. Iran’s majestic cities like Isfahan and Tehran came into focus as the Silk Road tried to weave in Persian trade. Journeying westward, it discovered Mesopotamia, with the cities of Babylon and Nineveh (now part of Iraq) facilitating an intermingling of the East and West. In Anatolia, the peninsula of land that today constitutes the Asian portion of Turkey, cities such as Antioch and Ephesus served as dynamic trading posts. Further west, we encounter the vibrant cities of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and Venice, showcasing how the Silk Road’s tendrils stretched into the heart of Europe. Egypt’s Alexandria and Cairo too stand testament to the route’s enduring influence.

Since the trading system operated as a chain with merchants moving products back and forth from one trade centre to the next, caravans did not travel the entire distance. The main commodities that could be exchanged were luxury items like silk, which as a high-value, low-bulk commodity made it ideal for long-distance trade along the Silk Road.

However, silk was not the only good to traverse the Silk Road. As Frances Wood writes in his 2002 book The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years In The Heart Of Asia, “China traded silk, teas, and porcelain, while India traded spices, ivory, textiles, precious stones, and pepper, and the Roman Empire exported gold, silver, fine glassware, wine, carpets, and jewels.” Wood writes that although the term Silk Road implies a continuous journey between China and Rome, in reality goods were transported by an assortment of intermediaries through a variety of routes, which were traded in the vibrant markets of the oasis towns.

The Silk Road enjoyed great prominence for nearly 15 centuries, facilitating the spread of ideas, cultures and goods from Asia to Europe. It peaked during the Mongolian Empire (13th century) when China and Central Asia were controlled by Mongol Khans. The Khans, despite being ruthless conquerors, were also proponents of global trade. However, with the rise of prominent sea routes between Europe and Asia and Europe and America in the 15th century, trade along the Silk Road virtually ended.

Although the enduring concept of the Silk Road is steeped in our collective memory, the term itself was coined in 1877 by the eminent German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, and only gained popularity in the 20th century. According to Susan Whitfield, Professor of Silk Road Studies at the University of East Anglia, the Silk Road was largely conceptualised by marketers. “There is no doubt that the Silk Road is a romantic oversimplification of what was a complex economic system involving a network of trade routes,” Whitfield wrote.

Whitfield is not alone in her assumptions. Ravi Mishra, the Deputy Director of the Nehru Museum in Delhi, puts forward a compelling argument for why the Silk Road, as a 10,000-km trade route, was unlikely to have existed as it is now portrayed. In a journal article for the Indian Historical Review, Mishra states that “the evidence for direct trade links between the Roman Empire and Han China is almost non-existent, and that it remains highly insufficient till the emergence in the thirteenth century of the vast Mongol Empire, which for the first time brought the far-flung parts of Eurasia under a broadly common political and economic architecture.”

Whitfield and Mishra both acknowledge that there were trade routes between Asia and Europe dating back to the 2nd century BCE but argue that those trade routes were neither contagious nor widely used from end to end. In fact, according to Mishra, the Silk Road was not a singular road at all, and was not the work of the Chinese but rather the nomadic civilisations of Central Asia. He writes, “What is described as the Silk Road or Roads was in reality the entire network of land routes connecting various parts of Eurasia with its core in Central or Inner Asia.”

In an earlier interview with Indian Express, the historian William Dalrymple argued that the Silk Road is primarily a Sino-centric construct that detracts from the importance of other trade routes, notably those passing through the Indian subcontinent. Describing the myth of the Silk Road, Dalrymple acknowledges that the route may have existed during the 13th century, but was largely inexistent or inconsequential before that. Additionally, he states that while silk may have been traded as far as Rome, it was primarily through the ports of India. In fact, he writes, during the Roman period, “there’s no evidence that China and Europe knew of each other’s existence beyond the realm of legend.”

Cross-cultural ties

Most academics agree that the Silk Road was a largely romanticised concept describing not one single ancient route but instead a myriad of smaller trade routes but that alone does not diminish its significance. Whether it was a direct route between China and Rome or a series of smaller routes between Asia and Europe, the Silk Road (or Roads) was responsible for connecting civilisations and cultures.

For India, the Silk Road positioned the subcontinent as a middleman between China and Rome. The Chinese traded their silk with Indians for precious stones and metals and then Indians would trade that silk with the Roman Empire. As Subhakanta Behera writes in India’s Encounter with the Silk Road, “from the Indian perspective, the importance of the Silk Road was not so much because of its trade and commercial value but also because of its being the highway for the movement of culture and ideas.” For example, Brahminism imported from India-influenced religions such as Zoroastrianism in Persia and Islam in Central Asia. According to Behera, similarly, Buddhism was an area of “mutual interaction” between India and the Silk Road countries, along with Islam which was brought to India by Muslim preachers, traders and rulers.

The Silk Road also conveyed crucial innovations. Western traders from the past appear to have brought into China technologies like wheeled transportation, several kinds of metallurgy, and so on. Meanwhile, pivotal ideas from China were brought to the West, including the creation of paper and gunpowder.

During the Han era, paper was created, presumably just as the Silk Road commerce was starting to take hold. Paper quickly replaced the slender wooden strips or awkward rolls of silk that the Chinese had previously used for writing and quickly became the preferred writing medium across East Asia. In Samarkand, during the Mongol era in the 13th and 14th centuries, a group of Chinese labourers established a paper manufacturing business. Paper swiftly replaced other writing materials across the majority of western Eurasia as a result of their product’s rapid expansion through commerce and imitation.

Similarly, gunpowder was created in the ninth century by Chinese alchemists or monks, most likely by accident, by “heating sulphur, realgar and saltpetre together with honey, producing smoke and flames that burned everything,” as described in a Taoist document from that era. It didn’t take long to realise that this mixture caused a powerful explosion when put in a container owing to the overpressure created by the significant volume of gas expelled. The explosive dust technology left China and journeyed through Asia before making its way to Europe through the Silk Road in the 13th century. It was swiftly put to use for military objectives in the West, enabling the creation of new weapon technologies which proved crucial to the subsequent conquest of the world by European nations.

Like the destructive power of gunpowder, the Silk Road also transported deadly diseases such as the bubonic plague. In Geographies of a Plague, Mark Welford explains that the plague travelled from Asia and North Africa — where it killed 25 million people over three years — to Europe largely via the Silk Road.

During the time of the Islamic Golden Age however, the Silk Road was responsible for the permeation of radical ideas and philosophies. Cities like Damascus, Isfahan, Samarkand, Kabul and Kashgar were hubs of scholarly thought, hosting outstanding scholars who expanded the boundaries of their fields. As Oxford historian Peter Frankopan writes in The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, “for centuries before the early modern era, the intellectual centres of excellence of the world, the Oxfords and Cambridges, the Harvards and Yales, were not located in Europe or the west, but in Baghdad and Balkh, Bukhara and Samarkand.”

The civilisations, towns, and populations that resided along the Silk Roads flourished and transformed as they traded and shared ideas, learned from one another and borrowed from them, thus in turn, spurring advancements in philosophy, the sciences, language, and religion. The exchange of languages and writing systems was also a significant part of the Silk Road’s cultural transmission. As people from different regions interacted, they often adopted and adapted each other’s scripts and writing systems. This facilitated the translation of texts and the spread of written knowledge.

Alluding to the profound importance of the route, Frankopan writes that “the Silk Roads opened up new ways to view the past and showed a world that was profoundly interconnected, where what happened on one continent had an impact on another, where the after-shocks of what happened on the steppes of Central Asia could be felt in North Africa, where events in Baghdad resonated in Scandinavia, where discoveries in the Americas altered the prices of goods in China and led to a surge in demand in the horse markets of northern India.”