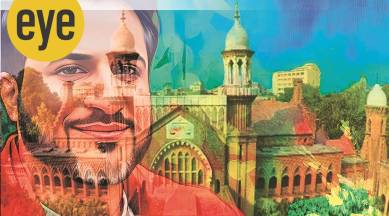

Where love was without boundaries

In Pakistan, friends welcomed me at celebrated tables, inspired me with daring sessions at the Lahore Literature Festival and regaled me with stories of the city

Somewhere in Manhattan, New York City (NYC), lie pages from my diary when I was nine years old. They are full of ant-lines of connecting dots showing my thoughts; they hold my first poems and odes to some of my favourite teachers and classmates. I last remember reading them in my early thirties. And then in a move from one apartment to another, I either lost my diary or had it safely in a box. There are poems I wrote whose lines I remember, and some whose words evade me entirely, but the one I remember most is the epitaph I wrote, instructing my mother to use it on the stone placed atop my cremated ashes in Lahore, Pakistan, if I were to predecease her.

When I was young, we spent the summers in Mussoorie and Nainital, two charming towns in the Himalayas. My mom would take us to the cemeteries there. We developed a deeper appreciation for poetry and words reading the epitaphs on gravestones. Some bits had familiar poetry on them, while some were captivatingly new and inspiring. It connected us to the cycles of nature, of life and death. We collected driftwood as decoration for our Delhi home or as gifts for friends. Pine cones would be used as Christmas decorations and twigs for bonfires. The scent of the woods, the silence of the cemetery, and the words on the tombstones gave me an understanding of what influence ancestry has upon our lives and how it continues to affect us after death.

Nana, my maternal grandfather, was very proud of his childhood and youth in Lahore, especially his schooling and days at Government College Lahore. He would speak of the city as a fertile land for agriculture and a prolifically lush breeding ground for ideas and aspirational education. Nana spoke of the 17th-century Badshahi Mosque and the red sandstone with marble inlay that exemplified Mughal architecture as well as the craftsmanship that glorified the strengths of Indian talent. He spoke of Anarkali Bazaar and its incredible chaat and street foods, the samosas and jalebis in particular. I remember hearing about Heera Mandi, and the tameez and tehzeeb that permeated the by-lanes of this red-light district. I heard of the gardens and the tombs, the canals and the hills. Every story about Lahore was laced with emotion and rich metaphors linking the two nations and their people as one.

As I flew from Delhi to Amritsar and then travelled by car from the airport to the Wagah Border, where I crossed on foot from India into Pakistan, I felt the presence of Nana and my paternal uncle, Hargobind Prasad Bhatnagar, also a Lahorian, who retired as the Director General of the Border Security Force of India. These two proud Lahorians, with hearts and minds of great empathy and wisdom, were two sons of India who lived by the Vedic Hindu diktat of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam – one village, one world, one family.

The immigration officers on both sides seemed rather excited to see me travelling from India into Pakistan. They reassured me with stories of people who returned from Pakistan having gotten more comfort and love than they could have ever imagined. They reminded me of our shared histories and pasts, our love of cricket and ghazals.

I crossed the border without any fear or hesitation and found Marina Fareed, my friend and host, the author of You Are Invited (AuntyM, 2023), waiting to receive me with her wholesome, heartwarming smile. Seeing Marina brought back fond memories of being with her and her husband, Shaukat, in NYC. As the days unfurled and I experienced Lahore, I found in her presence and everything she generously arranged for me, the blessings and affection of my Nana and Phupaji.

Nana always said Jisne Lahore Nai Dekhya, O Jamyai Nai (One who hasn’t seen Lahore is yet to be born). Ever since I’ve returned to Delhi, I have felt a new spate of energy and I feel much more fulfilled. I have seen the land that was my Nana’s old stomping ground and visited the nation to which my musical icon Farida Khanum belonged. I have enjoyed the peerless generosity and hospitality of Marina and Shaukat in their Lahore home, have been invited to parties with hundreds of guests and some very intimate ones, all done to welcome me. I met my pen pals Ashar Ahmed Farooqui and Awais Akber after three-plus years of Insta-friendship, and I have spoken and moderated a session at the Lahore Literature Festival’s 10th edition last month.

Almost two decades ago, I lost my diary and with it many accounts of my life as a young adult. My visit across the toxic border that separates Pakistan from India gave me a palpably real and awe-inspiring connection to a land I had fantasised about, romanced and revered since my pre-teens. As Marina opened doors to the most celebrated tables of Lahore, as Ashar and Awais opened their hearts and city to me through their tales and guided tours, and as I warmed the cockles of my heart with inspiringly daring sessions at the Lahore Literature Festival, I soaked in the loving affection and caring generosity being showered upon me by new friends who, with each morsel that I savoured, were turning into old and dear friends for life. Architectural gems, museums and palaces, tourist destinations, and the wonders of the world – they are all there for people to visit and be moved by. What I gained in my travel to the city of my grandfather’s heart, the city where I want my ashes scattered after my passing and cremation, was a connection to my past, a fulfillment in my present, having realised a dream of 40 years, and hope for a future where I can be united with my loved ones in Pakistan.