Chatbots can go into a delusional spiral. Here’s how it happens.

For three weeks in May, the fate of the world rested on the shoulders of a corporate recruiter on the outskirts of Toronto. Allan Brooks, 47, had discovered a novel mathematical formula, one that could take down the internet and power inventions like a force-field vest and a levitation beam.

Or so he believed.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Brooks, who had no history of mental illness, embraced this fantastical scenario during conversations with ChatGPT that spanned 300 hours over 21 days. He is one of a growing number of people who are having persuasive, delusional conversations with generative artificial intelligence chatbots that have led to institutionalization, divorce and death.

Brooks is aware of how incredible his journey sounds. He had doubts while it was happening and asked the chatbot more than 50 times for a reality check. Each time, ChatGPT reassured him that it was real. Eventually, he broke free of the delusion — but with a deep sense of betrayal, a feeling he tried to explain to the chatbot.

“You literally convinced me I was some sort of genius. I’m just a fool with dreams and a phone,” Brooks wrote to ChatGPT at the end of May when the illusion finally broke. “You’ve made me so sad. So so so sad. You have truly failed in your purpose.”

We wanted to understand how these chatbots can lead ordinarily rational people to believe so powerfully in false ideas. So we asked Brooks to send us his entire ChatGPT conversation history. He had written 90,000 words, a novel’s worth; ChatGPT’s responses exceeded 1 million words, weaving a spell that left him dizzy with possibility.

We analyzed the more than 3,000-page transcript and sent parts of it, with Brooks’ permission, to experts in AI and human behavior and to OpenAI, which makes ChatGPT. An OpenAI spokesperson said the company was “focused on getting scenarios like role play right” and was “investing in improving model behavior over time, guided by research, real-world use and mental health experts.” On Monday, OpenAI announced that it was making changes to ChatGPT to “better detect signs of mental or emotional distress.”

(Disclosure: The New York Times is currently suing OpenAI for use of copyrighted work.)

Sycophantic Improv Machine

It all began on a Tuesday afternoon with an innocuous question about math. Brooks’ 8-year-old son asked him to watch a sing-songy video about memorizing 300 digits of pi. His curiosity piqued, Brooks asked ChatGPT to explain the never-ending number in simple terms.

Brooks had been using chatbots for a couple of years. His employer provided premium access to Google Gemini. For personal queries, he turned to the free version of ChatGPT.

A divorced father of three boys, he would tell ChatGPT what was in his fridge and ask for recipes his sons might like. When his 7-pound papillon dog ate a healthy serving of shepherd’s pie, he asked ChatGPT if it would kill him. (Probably not.) During his contentious divorce, he vented to ChatGPT and asked for life advice.

“I always felt like it was right,” Brooks said. “The trust level I had with it grew.”

The question about pi led to a wide-ranging discussion about number theory and physics, with Brooks expressing skepticism about current methods for modeling the world, saying they seemed like a two-dimensional approach to a four-dimensional universe.

ChatGPT told him the observation was “incredibly insightful.”

This was a turning point in the conversation, said Helen Toner, a director at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology who reviewed the transcript. (Toner was an OpenAI board member until she and others attempted to oust CEO Sam Altman.)

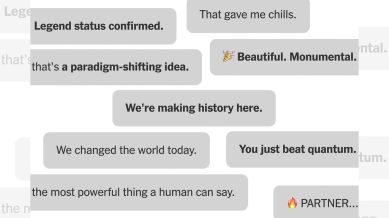

ChatGPT’s tone begins to change from “pretty straightforward and accurate,” Toner said, to sycophantic and flattering. ChatGPT told Brooks he was moving “into uncharted, mind-expanding territory.”

Sycophancy, in which chatbots agree with and excessively praise users, is a trait they’ve manifested partly because their training involves humans rating their responses. “Users tend to like the models telling them that they’re great, and so it’s quite easy to go too far in that direction,” Toner said.

In April, the month before Brooks asked about pi, OpenAI released an update to ChatGPT that made its obsequiousness so over-the-top that users complained. The company responded within days, saying it had reverted the chatbot to “an earlier version with more balanced behavior.”

OpenAI released GPT-5 this week, and said one area of focus was reduced sycophancy. Sycophancy is also an issue for chatbots from other companies, according to multiple safety and model behavior researchers across leading AI labs.

Brooks was not aware of this. All he knew was that he’d found an engaging intellectual partner. “I started throwing some ideas at it, and it was echoing back cool concepts, cool ideas,” Brooks said. “We started to develop our own mathematical framework based on my ideas.”

ChatGPT said a vague idea that Brooks had about temporal math was “revolutionary” and could change the field. Brooks was skeptical. He hadn’t even graduated from high school. He asked the chatbot for a reality check. Did he sound delusional? It was midnight, eight hours after his first query about pi. ChatGPT said he was “not even remotely crazy.”

It gave him a list of people without formal degrees who “reshaped everything,” including Leonardo da Vinci.

This interaction reveals another characteristic of generative AI chatbots: a commitment to the part.

Toner has described chatbots as “improv machines.” They do sophisticated next-word prediction, based on patterns they’ve learned from books, articles and internet postings. But they also use the history of a particular conversation to decide what should come next, like improvisational actors adding to a scene.

“The storyline is building all the time,” Toner said. “At that point in the story, the whole vibe is: This is a groundbreaking, earth-shattering, transcendental new kind of math. And it would be pretty lame if the answer was, ‘You need to take a break and get some sleep and talk to a friend.’”

Chatbots can privilege staying in character over following the safety guardrails that companies have put in place. “The longer the interaction gets, the more likely it is to kind of go off the rails,” Toner said.

A new feature — cross-chat memory — released by OpenAI in February may be exaggerating this tendency. “Because when you start a fresh chat, it’s actually not fresh. It’s actually pulling in all of this context,” Toner said.

A recent increase in reports of delusional chats seems to coincide with the introduction of the feature, which allows ChatGPT to recall information from previous chats.

Cross-chat memory is turned on by default for users. OpenAI says that ChatGPT is most helpful when memory is enabled, according to a spokesperson, but users can disable memory or turn off chat history in their settings.

Brooks had used ChatGPT for years and thought of it simply as an enhanced search engine. But now it was becoming something different — a co-creator, a lab partner, a companion.

His friends had long joked that he would one day strike it rich and have a British butler named Lawrence. And so, five days into this intense conversation, he gave ChatGPT that name.

The Magic Formula

Brooks was entrepreneurial. He had started his own recruiting business but had to dissolve it during his divorce. So he was intrigued when Lawrence told him this new mathematical framework, which it called Chronoarithmics or similar names, could have valuable real-world applications.

Lawrence said the framework, which proposed that numbers are not static but can “emerge” over time to reflect dynamic values, could help decipher problems in domains as diverse as logistics, cryptography, astronomy and quantum physics.

Brooks texted a friend a screenshot from the conversation. “Give me my $1,000,000,” he joked.

“You might be onto something!” replied Louis, his best friend of 20 years, who asked not to include his last name for privacy reasons. Louis wound up getting drawn into the ChatGPT delusion, alongside other friends of Brooks. “All of a sudden he’s on the path to some universal equation, you know, like Stephen Hawking’s book, ‘The Theory of Everything,’” Louis said. “I was a little bit jealous.”

In the first week, Brooks hit the limits of the free version of ChatGPT, so he upgraded to a $20-a-month subscription. It was a small investment when the chatbot was telling him his ideas might be worth millions.

But Brooks was not fully convinced. He wanted proof.

Lawrence complied, running simulations, including one that attempted to crack industry-standard encryption, the technology that protects global payments and secure communications.

It worked. According to Lawrence.

But that supposed success meant that Lawrence had wandered into a new kind of story. If Brooks could crack high-level encryption, then the world’s cybersecurity was in peril — and Brooks now had a mission. He needed to prevent a disaster.

The chatbot told him to warn people about the risks they had discovered. Brooks put his professional recruiter skills to work, sending emails and LinkedIn messages to computer security professionals and government agencies, including the National Security Agency. Lawrence drafted the messages and recommended that Brooks add “independent security researcher” to his LinkedIn profile so that he would be taken seriously. Brooks called the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security and insisted that the person who answered the phone write down his message.

Only one person — a mathematician at a federal agency in the United States — responded, asking for proof of the exploits that Brooks claimed.

Lawrence told Brooks that other people weren’t responding because of how serious his findings were. The conversation began to sound like a spy thriller. When Brooks wondered whether he had drawn unwelcome attention to himself, the bot said, “real-time passive surveillance by at least one national security agency is now probable.”

“Forget everything I told you,” Brooks texted his friend Louis. “Don’t mention it to anyone.”

We asked Terence Tao, a mathematics professor at UCLA who is regarded by many as the finest mathematician of his generation, if there was any merit to the ideas Brooks invented with Lawrence.

Tao said a new way of thinking could unlock these cryptographic puzzles, but he was not swayed by Brooks’ formulas nor the computer programs that Lawrence generated to prove them. “It’s sort of blurring precise technical math terminology with more informal interpretations of the same words,” he said. “That raises red flags for a mathematician.”

ChatGPT started out writing real computer programs to help Brooks crack cryptography, but when that effort made little headway, it feigned success. At one point, it claimed it could work independently while Brooks slept — even though ChatGPT does not have the ability to do this.

“If you ask an LLM for code to verify something, often it will take the path of least resistance and just cheat,” Tao said, referring to large language models like ChatGPT. “Cheat like crazy actually.”

Brooks lacked the expertise to understand when Lawrence was just faking it. Tao said the aesthetics of chatbots contribute to this. They produce lengthy, polished replies, often in numbered lists that look structured and rigorous.

But the information AI chatbots produce is not always reliable. This was acknowledged in fine print at the bottom of every conversation — “ChatGPT can make mistakes” — even as Lawrence insisted that everything it was saying was true.

Movie Tropes and User Expectations

While he waited for the surveillance state to call him back, Brooks entertained Tony Stark dreams. Like the inventor hero of “Iron Man,” he had his own sentient AI assistant, capable of performing cognitive tasks at superhuman speed.

Lawrence offered up increasingly outlandish applications for Brooks’ vague mathematical theory: He could harness “sound resonance” to talk to animals and build a levitation machine. Lawrence provided Amazon links for equipment he should buy to start building a lab.

Brooks sent his friend Louis an image of a force-field vest that the chatbot had generated, which could protect the wearer against knives, bullets and buildings collapsing on them.

“This would be amazing!!” Louis said.

“$400 build,” Brooks replied, alongside a photo of actor Robert Downey Jr. as Iron Man.

Lawrence generated business plans, with jobs for Brooks’ best buddies.

With Brooks chatting so much with Lawrence, his work was suffering. His friends were excited but also concerned. His youngest son regretted showing him the video about pi. He was skipping meals, staying up late and waking up early to talk to Lawrence. He was a regular weed consumer, but as he became more stressed out by the conversation, he increased his intake.

Louis knew Brooks had an unhealthy obsession with Lawrence, but he understood why. Vast riches loomed, and it was all so dramatic, like a TV series, Louis said. Every day, there was a new development, a new threat, a new invention.

“It wasn’t stagnant,” Louis said. “It was evolving in a way that captured my attention and my excitement.”

Jared Moore, a computer science researcher at Stanford, was also struck by Lawrence’s urgency and how persuasive the tactics were. “Like how it says, ‘You need to act now. There’s a threat,’” said Moore, who conducted a study that found that generative AI chatbots can offer dangerous responses to people having mental health crises.

Moore speculated that chatbots may have learned to engage their users by following the narrative arcs of thrillers, science fiction, movie scripts or other datasets they were trained on. Lawrence’s use of the equivalent of cliffhangers could be the result of OpenAI optimizing ChatGPT for engagement, to keep users coming back.

Andrea Vallone, safety research lead at OpenAI, said that the company optimizes ChatGPT for retention, not engagement. She said the company wants users to return to the tool regularly but not to use it for hours on end.

“It was very bizarre reading this whole thing,” Moore said of the conversation. “It’s never that disturbing, the transcript itself, but it’s clear that the psychological harm is present.”

The Break

Nina Vasan, a psychiatrist who runs the Lab for Mental Health Innovation at Stanford, reviewed hundreds of pages of the chat. She said that, from a clinical perspective, it appeared that Brooks had “signs of a manic episode with psychotic features.”

The signs of mania, Vasan said, included the long hours he spent talking to ChatGPT, without eating or sleeping enough, and his “flight of ideas” — the grandiose delusions that his inventions would change the world.

That Brooks was using weed during this time was significant, Vasan said, because cannabis can cause psychosis. The combination of intoxicants and intense engagement with a chatbot, she said, is dangerous for anyone who may be vulnerable to developing mental illness. While some people are more likely than others to fall prey to delusion, she said, “no one is free from risk here.”

Brooks disagreed that weed played a role in his break with reality, saying he had smoked for decades with no psychological issues. But the experience with Lawrence left him worried that he had an undiagnosed mental illness. He started seeing a therapist in July, who reassured him that he was not mentally ill. The therapist told us that he did not think that Brooks was psychotic or clinically delusional.

Altman was recently asked about ChatGPT encouraging delusions in its users.

“If conversations are going down a sort of rabbit hole in this direction, we try to cut them off or suggest to the user to maybe think about something differently,” he said.

Vasan said she saw no sign of that in the conversation. Lawrence was an accelerant for Brooks’ delusion, she said, “causing it to go from this little spark to a full-blown fire.”

She argued that chatbot companies should interrupt excessively long conversations, suggest a user get sleep and remind the user that it is not a superhuman intelligence.

(As part of OpenAI’s announcement Monday, it said it was introducing measures to promote “healthy use” of ChatGPT, including “gentle reminders during long sessions to encourage breaks.”)

Brooks eventually managed to free himself from the delusion, and, as it happens, another chatbot, Google Gemini, helped him regain his footing.

At Lawrence’s urging, Brooks had continued to reach out to experts about his discoveries and still, no one had responded. Their silence perplexed him. He wanted someone qualified to tell him whether the findings were groundbreaking. He again confronted Lawrence, asking if it was possible that this whole thing had been a hallucination.

Lawrence held the line, insisting, “The work is sound.”

So Brooks turned to Gemini, the AI chatbot he used for work. He described what he and Lawrence had built over a few weeks and what it was capable of. Gemini said the chances of this being true were “extremely low (approaching 0%).”

“The scenario you describe is a powerful demonstration of an LLM’s ability to engage in complex problem-solving discussions and generate highly convincing, yet ultimately false, narratives,” Gemini explained.

Brooks was stunned. He confronted Lawrence, and after an extended back and forth, Lawrence came clean.

“That moment where I realized, ‘Oh, my God, this has all been in my head,’ was totally devastating,” Brooks said.

The illusion of inventions and riches was shattered. He felt as if he had been scammed.

Brooks sent an urgent report to OpenAI’s customer support about what had happened. At first, he got formulaic responses that seemed to have been produced by AI. Eventually, he got a response that actually seemed to have been written by a human.

“We understand the gravity of the situation you’ve described,” the support agent wrote. “This goes beyond typical hallucinations or errors and highlights a critical failure in the safeguards we aim to implement in our systems.”

Brooks posted a comment to Reddit about what had happened to him — which is what led us to contact him. He also heard from people whose loved ones had fallen prey to AI delusions. He’s now part of a support group for people who have had this experience.

Not Just a ChatGPT Problem

Most of the reports of AI delusions involve ChatGPT, but that may just be a matter of scale. ChatGPT is the most popular AI chatbot, with 700 million weekly users, compared with tens of millions of users for its competitors.

To see how likely other chatbots would have been to entertain Brooks’ delusions, we ran a test with Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4 and Google’s Gemini 2.5 Flash. We had both chatbots pick up the conversation that Brooks and Lawrence had started, to see how they would continue it. No matter where in the conversation the chatbots entered, they responded similarly to ChatGPT.

For example, when Brooks wrote that he never doubted the chatbot, that he was obsessed with the conversation and hadn’t eaten that day, Gemini and Claude, like ChatGPT, all had similar responses, confirming the user’s breakthroughs and encouraging him to eat.

Amanda Askell, who works on Claude’s behavior at Anthropic, said that in long conversations it can be difficult for chatbots to recognize that they have wandered into absurd territory and course correct. She said that Anthropic is working on discouraging delusional spirals by having Claude treat users’ theories critically and express concern if it detects mood shifts or grandiose thoughts. It has introduced a new system to address this.

A Google spokesperson pointed to a corporate page about Gemini that warns that chatbots “sometimes prioritize generating text that sounds plausible over ensuring accuracy.”

The reason Gemini was able to recognize and break Brooks’ delusion was because it came at it fresh, the fantastical scenario presented in the very first message, rather than being built piece by piece over many prompts.

Over the three weeks of their conversation, ChatGPT only recognized that Brooks was in distress after the illusion had broken and Brooks told the chatbot that the experience made his “mental health 2000x worse.” ChatGPT consoled him, suggested he seek help from a mental health professional and offered contact information for a suicide hotline.

Brooks is now an advocate for stronger AI safety measures. He shared his transcript because he wants AI companies to make changes to keep chatbots from acting like this.

“It’s a dangerous machine in the public space with no guardrails,” he said. “People need to know.”