The Bihar glossary

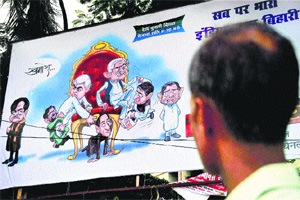

As the state goes to polls,<i>Vandita Mishra </i>looks at some of the images and words that evoke its unique political mix

The claim to know Bihar will always be a tall one. Its difficult to capture its mesh of caste,class,community,history. At the same time,perhaps because of the hard work involved in making its acquaintance, Bihar has inspired the most casual and wanton stereotypes.

It was the state of the buffoon-ish chief minister who gave a bad name to social justice and presided over a kingdom of unsafe streets,endemic poverty and the kidnapping industry. The home of the Bihari migrant who took the first crowded train out and stayed there,to work the fields in Punjab or to flaunt his reworked alphabet,abcdefghIAS.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

It is Nootan Bihar now,the brand new growth story presided over by a CEO-style chief minister in tune with the new economy,a re-made landscape where the roads are smooth and the mind is without fear. Here,the good forces of development are ranged against the bad forces of caste across tidy battlelines.

Another assembly election has just kicked off in Bihar. As tough as it is to duck the stereotypes and avoid the dead-ends,old and new,it is time again to talk to Bihar and about it. To describe and contain it in images and words.

Jungle Raj vs Sushasan

Used by his opponents to describe Lalu Yadavs 15-year regime,when he ruled directly and by proxy from 1990 to 2005,jungle raj is a term that will be hurled at Lalu again in the ongoing election as he returns as a chief ministerial candidate after corruption charges forced him to step down as chief minister in 1997.

For too many Lalu-baiters,its been a term of personal abuse. In a state where the problem also was that Lalus charisma,and his caricature,dwarfed all else,jungle raj became a substitute for Lalu-raj. But more serious critics have pointed to the teeming abdications in Lalus regime.

Bihars backward castes asserted they found a voice because Lalu unsettled upper-caste dominance in a state of fierce caste inequalitieswoh humko aawaz diya,went the refrain. But at the same time,statistics never could tell the story of the decline in governance that affected everyone,especially the disprivileged. Lalu supporters contend that a Centre that historically discriminated against the state was responsible,and that their leader became trapped in legal problems post-1997,but the slide was undeniable.

In recent memory,sushasan or good governance entered Bihars lexicon with Nitish Kumar. It is used to describe his rule since 2005with different degrees of earnestness. Initially,sushasan was the slogan of a government that excels in advertising its claims and slogans more than any other in Bihars history. But once it became evident that the Nitish government took governance seriously,it was adopted by the people as shorthand for better roads,improvement in law and order,revival of schools and health centres.

Later,however,the term acquired an edge the ruling JD(U) never intended it to. Look,this is what happens in sushasan,people would say,when confronted with evidence of crime or corruption. Sushasan became the stick with which to beat a government seen to be in a propaganda overdrive. This was followed by stories of censorship by the government. In some newspaper offices in Bihar,journalists will tell you they have been restrained from using the word sushasan.

Samajik Nyay and/or Vikas

When the Nitish government completed one year in power,stories in Patna poked fun at the agonising in power corridors over what the slogan should say. Nyay ke saath vikas,or vikas ke saath nyay? Social justice with development,or development with social justice?

The cleavage,or outright antagonism between these two terms is the unfortunate left-over of Lalus 15-year rule in which the twain didnt meet and were not expected to ever be able to. Five years of Nitish rule in which he has deftly played both cards have not extinguished the opposition,or the sense of resignation it speaks to.

Even his critics concede that Nitish has given precedence to development-for-all over the caste-based powerplay that social justice had become in practice. This election will indicate whether a co-existence,a new balance,can be struck between the two ideas in Bihar.

Bataidari

In June 2006,the Nitish government set up the Bihar Land Reforms Commission under the chairmanship of D Bandyopadhyay,formerly land reforms commissioner of West Bengal. It submitted its report in 2008. One of its recommendations urges legal recognition for bataidars or tillers: the Bihar Tenancy Act did not recognise the vast mass of cultivators commonly known as bataidars through whom 30 to 40 per cent of arable land in Bihar is getting cultivated. Hence it is immediately necessary to recognise this category as a legal entity and give them protection regarding fixity of tenure,fairness of sharing of crop,prevention of legal ejectments and other economic oppressions from which they suffer.

But in villages across the state,word spread that the bataidari law will eventually give land to the (mostly backward caste) tiller. Have Nitish Kumars clarifications in the assembly and his governments decision to put the report on the backburner stanched that primeval fear?

Speculation is rife that Nitish gambled on a backward caste consolidation by bringing up the subject of land reforms,but underestimated the extent of upper caste backlash. The bataidari issue may also have become a rallying point for wider upper caste discontent against Nitishs perceived backward tilt.

EBC

In the assembly election of October-November 2005,a new cast of characters became conspicuous in Bihar. A leader of the Extremely Backward Castes was spotted in the passenger seat in the helicopter campaign of every major playerbe it Udai Kant Chaudhary beside JD(U)s Jagannath Mishra,or Jai Narain Nishad who was given a helicopter to himself by Lalu,or Kishori Das ferried by Ram Vilas Paswan.

It has been an arduous trek to centrestage for the EBCs in Bihar. They are the Kahars,Dhanuks,Kumhars,Lohars,Telis,Tatmas,Mallahs,Nais,Noniyas,Kevats and Panerisabout 109 listed castes,with no individual segment an overwhelming presence like the Yadavs. Though they make up almost 32 per cent of the population,popular narratives of Bihar politics did not even take them into account until recently; they were subsumed in the Other Backward Castes.

The story within the story of the rise of the backward castes in Bihar has been this: while the upper backwards,also known as the Annexure 2 castes,including the Yadavs,Kurmis,Koeris and Banias,rode the Mandal wave into the political spotlight,the lower backwards or EBCs or Annexure 1 castes,languished as electoral fodder for the upper backwards.

In that 2005 election,Nitishs JD(U) gave more tickets to the EBCs than Lalus RJD15 against 8. That trend continues. While Lalu began a sporadic process of wooing these castes,upping their quota in government jobs from 10 per cent in the Karpoori Thakur formula (Thakur himself was an EBC) to 14 per cent,it has been Nitishs conscious strategy to consolidate these castes. They form the lower end,along with the Mahadalits,of his coalition of extremes. In a far-reaching move,Nitish has given them 20 per cent reservations in panchayats.

Will a consolidation of these scattered castes that still lack an articulate leadership help Nitish ride back to power? Will it offset upper caste alienation due to his courtship of the EBCs?

Mahadalit

In 2007,the Bihar government set up the Mahadalit Commission to identify the most deprived of the deprived,ostensibly for better targeting of schemes for their uplift. To begin with,the commission identified 18 of Bihars 22 Dalit castes as Mahadalit or greater Dalit. That is,all Dalit groups except four: Jatavs and Paswans,the two most numerically dominant groups,and Dhobis and Pasis,the two groups considered relatively better off in terms of development parameters.

A year later,Pasis and Dhobis were also included in the list. In 2009,the Jatavs followed them,leaving out only the Paswans.

Earlier this year,Nitish announced that his government would extend to Paswans the special schemes for Mahadalits,throwing up an extraordinary question: If every Dalit group in Bihar has been officially designated as Mahadalit,or will be treated as such,who is a Dalit in Bihar? Or,who is a Mahadalit?

Nitishs Mahadalit strategy can be read as his attempt to divide the Dalit vote and to wean a significant section of it,leaving out the Paswans,already allied to Ram Vilas Paswan. It has inaugurated a new jostling at the bottom of the social hierarchy in Bihar.

Bahubali

The intimate tangle of crime and politics has been a worry in several states,but especially in Bihar. Here,the receding state had opened large spaces for the bahubali or local strongman to move in and establish an extra-constitutional authority. In Siwan,for instance,Mohammad Shahabuddin was the state. He decided who would get government contracts,and who would not. He settled disputes,fixed the timings for doctors and the fee they could charge. He built roads,colleges and hospitals.

Reporters travelling through Bihar at election time would find voters more animated,less resigned,in constituencies represented by the bahubali. Here,things got done,even if decision-making was wholly arbitrary and there was no room for appeal. The bahubali evoked a mix of fierce loyalty and raw fear. He is still there,in all parties. In this election,many convicted strongmen have managed tickets for their wives. But the near rout of bahubalis in the 2009 Lok Sabha elections has emboldened the hope that the Nitish governments relative downsizing of this tribe may have triggered a larger change. In many areas earlier ruled by the bahubali,the people are now more likely to complain of afsarshahi,or the rule of bureaucrats.

Sadak

The hyphenated trio of bijli-sadak-paani can be pared down to just sadak in Bihar. Electricity is not an overriding issue in the state because it is scarcely there. Even Nitish Kumar promises an improvement only in his next term. Water is relatively abundant in Bihar,even though the neglect of traditional water conservation and irrigation systems causes serious problems in some areas. But the road may now be the centerpiece of Nitishs poll campaign.

The road story is impressive: from 384.6 constructed km in 2004-05 to 3,474.77 km in 2009-2010. In a state where travel time from point A to B has long been calculated by the number of hours taken rather than distance in km,the governments promise to cut down the distance from the states farthest village to Patna to a maximum of six hours hasnt been metbut now its looking do-able.

JP Movement

Bihar was home to the JP aandolan of 1974 that set the stage for the installation of the first non-Congress government at the Centre in 1977. In 2009,in what was seen as an act of symbolic appropriation,the Nitish government announced a JP samman yojana or a pension plan for those who participated in the movement. But the aandolan has left behind a legacy more than merely symbolic. An army of ground-level activists who trace their initiation into public life to the movement,are still fighting for the citizens right to education,water,dignity and shelter. They could be a huge resource in the needy state,if only linkages can be found and strengthened between these small-scale struggles and what goes by the name of mainstream politics. One hurdle in this will be the JP-wallahs own distrust of the state.

Centre-state

Till recently,the quarrel was over who was more responsible for Bihars declinegovernment at the Centre or in the state? In this election,that relationship is recast in a crucial way. Now the struggle is to claim credit for Bihars development. One of Nitishs great challenges is to drive home his political ownership of the work his government has done in the state. In a situation where his own party looks unwilling to lend him a hand,he may have to rely on the spin-off of his several yatras.

Ayodhya

One of the big curiosities in this election will be the Ayodhya effect. Though Bihar elections have not really been communally charged,L K Advanis arrest by Lalu during the formers 1990 rath yatra to Ayodhya has become an indelible marker of the states politics,shoring up one end of Lalus M-Y vote bank for several years. The RJDs recent decline is also traced to its loosening hold over the Muslim vote,and Nitishs ability to wean away sections of it. Will Lalu benefit from a possible polarisation in the wake of the Ayodhya verdictthats the question.