Keeping their child alive: As SC turns down family’s euthanasia plea, how the law has changed everyone’s life

For 11 years, Harish Rana has been lying still on a bed — the only sign of life an occasional cough. With the Supreme Court turning down the family’s plea for passive euthanasia for Harish, Vidheesha Kuntamalla visits their home to find how the law around death has changed everyone’s life

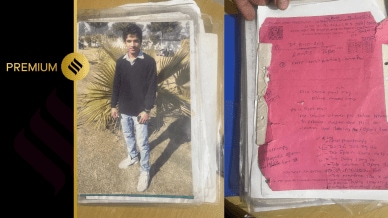

It’s a photograph taken in a park, “somewhere in Chandigarh”. Harish Rana, wearing a black pullover and white sneakers, a mobile phone in his left hand, strikes a pose in the winter sun.

“Look at him… This was when he was in college. He is posing for the camera,” smiles Ashok Rana, 63, gently stroking the photograph, straightening the tiny moisture bubbles trapped in between the plastic sheets of a file where it lay along with other documents. It’s a photograph from another time, of his son as a third-year civil engineering student at Chandigarh University.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Now 30, Harish lay in an adjacent room, his left arm strapped to the bed to restrain him and prevent him from falling, his limbs twisted and wasting. It’s a state he has been in for the last 11 years — a “100% disability” that has left him in a vegetative state, from which he has almost no chance of recovering, say doctors who have attended to him.

Ashok, weary with age and fatigue, struggles to keep memories of his eldest child alive. The photograph helps. As does a gastrostomy tube — filled with milk at times, beetroot puree at other times —that’s attached to Harish’s stomach. It is this that has helped keep Harish alive since 2013, when he fell from the fourth floor of his flat in Chandigarh and suffered severe head injuries.

But as the prayers and hopes of the initial years gave way to a gnawing realisation that Harish will never respond or get up again, Ashok and his wife Nirmala, 58, were weighed down by a nagging fear. “We are getting old. What will happen to him after we are gone? There is no one else to care for him. He will be left all alone, trapped in this state,” says Ashok.

It’s this fear that has prompted the ageing couple to seek what “no parent would wish for their child” — death by euthanasia.

In July, the Delhi High Court turned down the parents’ plea for passive euthanasia for their son, saying Harish was not being “kept alive mechanically and he is able to sustain himself without any extra external aid”.

Last month, the Supreme Court too declined their plea, with the CJI-led bench ruling that Harish’s was not a case of “passive euthanasia” as he was not completely dependent on life-support machines. The court, however, said it was “moved by the plight of the family” and asked the Centre to consider if arrangements could be made for Harish’s treatment and lodging. The next hearing in the case is expected to be held on September 10.

Manish Jain, the lawyer representing Harish Rana in the Supreme Court, says, “In our petition, we have asked the court to enlarge its definition of what all comes under the term ‘life support’…The petition was originally the mother’s painful decision as she was the one who started worrying about the deteriorating health condition of her son.”

Sitting on a thin mattress on the floor at his home in Ghaziabad, the documents strewn around him, Ashok rearranges the files one more time – his son’s medical reports, hospital receipts, petitions to courts and the countless letters that he has written seeking help and, now, euthanasia for Harish.

“I have lost count of the number of times I have gone through these documents. Still, I discover new things about my son every day. I found this photograph only a few days ago, I also found his mess card from college,” says Ashok, who retired in 2022 after 30 years of working in a catering firm, where he supplied food to clients.

A phone call on Rakshabandhan

Recalling the Rakshabandhan day of August 20, 2013, that turned their world upside down, Nirmala says she spoke to her son in the afternoon, after the day’s festivities had wrapped up.

“I called him and asked if he had tied the rakhi his younger sister had sent him. He said he was busy, but would do that soon,” recalls Nirmala.

That was the first time since he left home that Harish hadn’t come home for Rakshabandhan.

“Bhaiya had won several weightlifting competitions in college. That year, he stayed back because he had a crucial bout coming up in two days and wanted to focus on his training. Bhaiya loved three things: video games, football and working out at the gym,” says Harish’s brother Ashish, younger by three years, who works for an edtech firm.

Around 7.30 pm that day, the phone rang with terrible news. Ashok says the caller told him that Harish had fallen from the fourth floor of a building while attempting to jump “from one structure to another”.

“Why would our son attempt something so reckless?” wonders Ashok. It’s a question he has asked himself several times, but never found an answer to.

The family immediately set out for Chandigarh — it was around 1 am by the time they reached the hospital where Harish was admitted.

Nirmala says the sight of her son on the hospital bed, hands and legs restrained, broke her. “His teeth were chattering, and there were tears in his eyes,” she says, her voice trembling.

Harish was a teenager when he left his home in Mahavir Enclave to join college in Chandigarh — a polytechnic course, followed by civil engineering at Chandigarh University. Almost overnight, says Nirmala, he grew up.

“Until then, he avoided the smallest of chores at home. He was someone who would call us to his room and ask us to turn off his fan,” laughs Ashish, recalling how “bhaiya was a lot of fun… played a lot of pranks… But in Chandigarh, he became more responsible, and when he came home from college during vacations, he would help our mother with work and guide me.”

A bedside in Ghaziabad

After he was brought to Delhi from the Chandigarh hospital, Harish was taken straight to the AIIMS Trauma Centre, from where he was sent home four days later.

His medical records from Janakpuri Super Speciality Hospital, one of the 20-odd hospitals Harish was taken to in the initial years, show he has a “head injury with diffuse axonal injury with vegetative stage, quadriplegic. He is physically disabled and has 100% disability in relation to his whole body and is permanent in nature”.

Dr Shweta Singla, a neurologist who treated Harish at her private clinic in Delhi’s Dwarka for the first six years after the accident, told The Indian Express, “When I first saw him, he was unable to open his eyes or move his limbs. Since then, the family has approached me several times for medication and in times of emergencies. But in all these years, Harish has shown no improvement in his clinical status.”

Meanwhile, the family’s world shrank to Harish’s bedside, defined by the rhythms of his care. “Now everybody’s a doctor in our house,” says Ashok wryly.

From the time Nirmala and her son Ashish wake up at 5 every morning, their day is an unrelenting schedule of medication and care — sponge baths, massages, and physiotherapy sessions for Harish.

Twice a week, they lift Harish and place him on a wheelchair and give him a sponge bath, after which they dress his bed sores, place him back on the bed and carefully refit the gastrostomy tube. They also help him do physiotherapy sessions twice a day and give him a coconut oil massage for “better blood circulation”.

Through all this, Harish lies still on the bed, the only sign of life an occasional cough and the silent heave of his chest as he breathes.

In the initial years, the family clutched at every straw they could find. “My mother did all kinds of things to bring him back. For months, she would boil two litres of milk everyday, make khoya out of it and place it on my brother’s head, simply because someone suggested that would help. We also tried homoeopathy medicines. Nothing worked,” says Ashish.

For a while, the family also took Harish to RML, AIIMS and Apollo hospitals for Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy — a treatment that involves breathing pure oxygen in a pressurised environment — but gave up after he failed to respond.

It’s Nirmala who is in constant attendance by Harish’s bedside, rushing off to the kitchen to cook and to prepare his pureed food, but heading back every few minutes to attend to him – to feed him four times a day every four hours, rinse and wash the gastrostomy tube after every feed, empty the catheter, or simply to check on him. While she and her younger son Ashish share Harish’s room, Ashok sleeps in an adjacent room.

Ashish says that as “the glue that has kept us together”, his mother took it upon herself and shouldered much of the caregiving responsibility. “Earlier, mummy would lift bhaiya all by herself and place him on the wheelchair. But she can’t do that anymore. She has slowed down,” he says.

This year, there has been a new worry: the big bed sores that refuse to go away. “I make sure I turn his body to the side every hour,” says Nirmala.

The gastrostomy tube, too, has given them several anxious moments – in the early days, every time Harish was turned on his side, the tube would come off and the family had to rush him to hospital.

Pouring some milk from a steel glass into Harish’s gastrostomy tube, Nirmala says, “He used to love the aloo parathas I made. He would eat at least eight in one sitting. Now my heart breaks when I pour this into the tube,” she says. “Harish was so fit he could eat 10 to 12 bananas at a time,” adds Ashok.

Ashok says that with Harish bedridden, the family’s finances are always stretched thin. “We spent lakhs on our son’s medication and the hospital visits. Even now, the catheter, the gastrostomy tube have to be changed every few days. I had to support two other children and my wife with my salary of Rs 30,000. Now I have retired and all of us are dependent on my younger son’s income,” says Ashok.

To supplement his son’s income and his own monthly pension of Rs 3,600, Ashok sells sandwiches and burgers at a local cricket ground on weekends.

In 2021, they sold their home in Mahavir Enclave and relocated to Ghaziabad.

“We wanted Harish’s room to have some ventilation and some light. The house in Mahavir enclave had no ventilation and the lights had to be on all the time. Since we keep the airconditioner on in Harish’s room almost round the day, we thought we could save some money on electricity if we moved to another house with better ventilation,” says Ashok.

Over time, the hospital and doctor visits have gone down. “We have given up on hospitals,” Ashok says, recounting their endless wait for basic procedures at various medical facilities, their hopes rising and dipping with each doctor consultation.

All these years, Nirmala says, she had kept hoping for a miracle – that Harish would someday twitch a toe, move his hand a bit, call out to her. But now, she has given up.

“A decade is a long time… Even when doctors gave up hope, I was hopeful that my son would recover some day. But this year, after his bed sores got worse, I decided I cannot see my son suffer any more,” she says.