No Indian working in India has won a science Nobel in 94 years: Here’s why

The lack of success at the Nobel Prizes is often seen as a reflection of the state of Indian science. But other factors are also at play. We take a look.

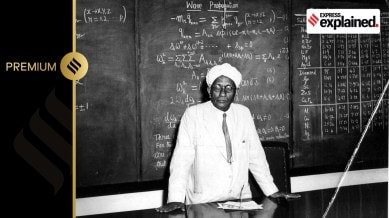

It has been 94 years since an Indian won a Nobel Prize in the sciences — Physics, Chemistry or Medicine — while working in India. CV Raman’s Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930 remains the only such honour. Three more Indian-origin scientists have won — Hargovind Khorana in Medicine in 1968, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in Physics in 1983, and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan in Chemistry 2009 — but they did their work outside India and were not Indian citizens when they were honoured.

The lack of success at the Nobel Prizes is often seen as a reflection of the state of Indian science. But other factors are also at play. We take a look.

India’s limitations

Inadequate attention on basic research, low levels of public funding, excessive bureaucracy, lack of incentives and opportunities for private research, and decay of research capabilities in universities are cited as some of the reasons suffocating India’s scientific potential. Few institutions are engaged in cutting edge research, and the number of researchers as a proportion of population is five times lower than the global average. The pool from which a potential Nobel winner can emerge, thus, is quite small.

Nominated, but didn’t win

It is not that there haven’t been other contenders for a science Nobel from India. Several scientists have indeed been nominated for these prizes. And at least a few others produced ground-breaking science but were never nominated.

Not anyone can get nominated for a Nobel Prize. Every year, a select group of hundreds to thousands of people — university professors, scientists, past Nobel laureates, and others — are invited to nominate potential candidates. A nomination for a Prize, therefore, means that the nominated scientist has produced Nobel-worthy work at least in the eyes of some respected peers.

Names of nominated candidates are not made public until at least 50 years later. And even this data is updated only periodically, not regularly. The nominations for Physics and Chemistry Prizes are available till 1970 while those for Medicine have been revealed only till 1953.

Among the 35-odd Indians figuring on the nomination lists that have been made public, six were scientists. Meghnad Saha, Homi Bhabha and Satyendra Nath Bose were nominated for the Physics prize, while G N Ramachandran and T Seshadri were nominated for Chemistry. The lone Indian nomination for Medicine or Physiology was Upendranath Brahmachari. All six were nominated multiple times by different nominators. A few British scientists, living and working in India in that period, also figure on the nomination list.

Disappointments

A notable omission is Jagadish Chandra Bose, the first person to have demonstrated wireless communication, way back in 1895. The 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics to Guglielmo Marconi and Ferdinand Braun was in recognition of the exact work that Bose had accomplished earlier than either of them. Bose, who did immensely influential work in plant physiology as well, was never even nominated for the award.

K S Krishnan was another scientist with a compelling case who was never nominated. A student and close collaborator of C V Raman in his laboratory, Krishnan is well acknowledged as the co-discoverer of Raman scattering effect, for which Raman alone was given the Nobel Prize in 1930.

Though the nominations after 1970 have not yet been revealed, at least one Indian scientist is very likely to have been considered for the Prize. CNR Rao’s work in solid state chemistry has long been considered worthy of a Nobel, but the honour has eluded him so far.

The most controversial omission of an Indian has been that of ECG Sudarshan, who was overlooked for the prize not once but twice. The Nobel Prizes in Physics, in 1979 and in 2005, were given for work in which the most fundamental contributions had come from Sudarshan. But Sudarshan, who passed away in 2018, had become an American citizen in 1965 and most of his work was accomplished in the United States.

Western dominance in the science Nobels

India is not the only country with an unimpressive record at the Nobel Prizes. Countries with much greater allocation of resources to scientific research, like China or Israel, have a surprisingly low number of Nobel Prizes in sciences. Of the 653 people who have won the Nobel Prize for Physics, Chemistry or Medicine, more than 150 belong to the Jewish community, an astoundingly high proportion. But Israel, considered the Jewish homeland, has won only four Nobel Prizes in science, all for Chemistry. This despite the fact that Israel figures very high on all the common indicators used to measure a country’s capabilities in science and technology, and is recognised globally for its scientific prowess.

Similarly, China, which has four times more researchers per million population than India, whose expenditure on research and development as a share of GDP is at least three times higher than India, and several of whose universities rank in the global top 50, has produced just three Nobel Prize winners in science till now.

South Korea, another scientific powerhouse that fares very well on research indicators, has got none.

The science Nobels have been overwhelmingly dominated by scientists from the United States and Europe, many of whom came from other countries in search of better scientific infrastructure and ecosystem. Only 13 of the 227 winners of Physics Prize, 15 of the 197 winners of Chemistry Prize, and 7 of the 229 winners of the Medicine Prize have come from Asia, Africa or South America. In fact, outside of North America and Europe, there have been only nine countries whose researchers have won a Nobel Prize in sciences. The largest number came from Japan, which has 21 of these.

While there have been occasional complaints of regional or racial bias, there is no denying the fact that the research ecosystem in the United States or Europe has remained unmatched.

China, which has been investing heavily in creating an ecosystem particularly focused on research in new technologies, like clean energy, quantum and artificial intelligence, might see its fortunes turning soon.

India, meanwhile, is lagging way behind countries like China, South Korea or Israel in building scientific capabilities or allocating resources for research. In the absence of a strong ecosystem and support for scientific research, India’s chances of winning more Nobel Prizes in science would remain dependent on the individual brilliance of its scientists.