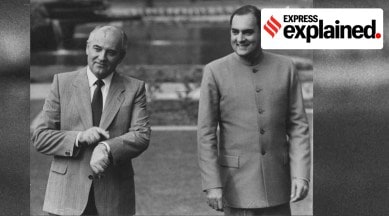

Why Rajiv Gandhi hailed Mikhail Gorbachev as a ‘crusader of peace’

The relationship between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi, two leaders whose fortunes rose and fell almost in tandem, inaugurated a five-year waltz between India and the erstwhile Soviet Union.

Mikhail Gorbachev, who died on Wednesday at the age of 92, came to the helm in the Soviet Union just a few months after a forced leadership change in India. Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984 led to her son Rajiv Gandhi assuming the mantle. The relationship between the two leaders, the Russian Rajiv’s senior by 15 years, inaugurated a five-year waltz between the two countries, ironically at a time when the Soviet Union itself was heading towards its eventual, spectacular collapse.

The fortunes of the two leaders rose and fell almost in tandem. Gorbachev succeeded Konstantin Chernenko as general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in March 1985, a little more than four months after Rajiv became Prime Minister. And in November 1989, as India voted to defeat Rajiv in that year’s parliamentary elections, the world was celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall that presaged the end of the Soviet Union.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Between May 1988 and February 1989, Gorbachev had pulled the Red Army out of Afghanistan. With the USSR falling apart, he was removed as leader of the CPSU in August 1991, and in December that year, the Soviet Union was formally dissolved.

Between 1985 and 1989, Rajiv and Gorbachev found enough common ground to mark a high point in India-Soviet relations — their differences over the Soviet leader’s idea of an “all-Asia forum” along the lines of the “common European home” notwithstanding. Rajiv, who had been labelled as a “pro-West” leader during his initial months in charge, belied Soviet fears of a change in the traditional relationship. At the same time, Rajiv did not flinch from telling Gorbachev that Asian security was “an old concept”, and that India was against “countries…interfering, intervening in areas outside their own”. (Indo-Soviet Relations: The Rajiv Era: Bushra Gohar, 1987).

Arms sales from the Soviet Union to India continued to define much of the bilateral ties, picking up after a slowdown in the late 1970s following Indira’s refusal to become part of a Soviet- led security compact in Asia.

From the mid-1980s, the USSR was supplying more sophisticated hardware to India than earlier. P V Narasimha Rao, defence minister in the Rajiv Gandhi cabinet, took a military delegation to Moscow for defence shopping and came back with several agreements.

Even Before Rajiv’s May 1985 visit to Moscow, Gorbachev had said in an interview to PTI that he had established a personal rapport with India’s PM, and the visit would bring the two leaders closer. Rajiv would declare later that it was “amazing how much we [he and Gorbachev] have in common” (The Soviet Union’s Partnership with India: Vojtech Mastny, 2010).

Rajiv would also say, at a time when Gorbachev himself was planning to end the Afghan occupation, that “it would be worse for all developing countries in the region if imperialism succeeded in strangling the revolution in Afghanistan”.

Another indication of the proximity between the two leaders came in October 1985, when Rajiv made a reportedly unscheduled stop in Moscow during a five-nation foreign tour that had taken him to the United Kingdom, Bahamas, Cuba, the United States, and the Netherlands. The surprise stop gave rise to much speculation as to its reason. It was reported later that Gorbachev wanted to get Rajiv’s assessment of Ronald Reagan before he met the US President in Geneva for disarmament talks scheduled for the following month.

Gorbachev visited India twice, in 1986 and 1988. He has written that when he went to India in 1986, his objective was to extend his disarmament initiatives in Europe to Asia, and to secure Indian co-operation in this task. It was Gorbachev’s first visit to a non-Warsaw Pact country after taking over as leader of the Soviet Union. India was willing, and Rajiv hailed Gorbachev as a “crusader for peace”.

Gorbachev’s address to India’s Parliament during the visit received hyperbolic coverage in the Indian and Soviet press, and was seen as a high point of Indian diplomacy. The Delhi Declaration was almost prescient in its new positioning of security as the development of the individual, and of the threats to security as food scarcity, illiteracy, and communalism, and also mentioning environmental security.

This period also saw lavish cultural exchanges between the two countries, with the Festival of India in the Soviet Union in July 1987 the centrepiece. “The message was loud and clear. The Kremlin has pulled out the stoppers, brushed aside previously unbreakable rules, and set a dozen precedents which have left Kremlin-watchers gasping in disbelief and South Block patting itself on the back for the coup. Moscow is signalling to India and the world that India is a very special friend indeed,” India Today reported. It was the time educated Indians started referring to the Soviet leader as Gorby.

But by then, Rajiv’s fortunes were on the wane, and there was vociferous opposition at home to the holding of the festival, as well as to his attendance in Moscow, even though it was a wildly successful visit from a foreign relations perspective. Gorbachev was reported as saying he had not spent so much time with any other foreign leader as he had with Gandhi during the visit. An agreement was signed for scientific and economic cooperation during the visit, and both sides held talks about the deteriorating security situation in the region, a reference to Pakistan without mentioning it by name.

But a disclosure by Gorbachev that he had also discussed with Rajiv the internal political situation in India added fuel to the domestic storm. The opposition BJP accused the Soviet Union of interfering in the presidential elections of that year, by pressuring India’s communist parties to not join hands with the opposition for the re-election of Giani Zail Singh, who had revolted against Rajiv. The CPI(M) and CPI would back Justice V R Krishna Iyer as their candidate. Finally, R Venkataraman was elected.

The collapse of the Soviet Union saw India reset its foreign policy, and helped by the liberalisation of the economy, New Delhi began repairing its ties with the US. But in 1998, when India tested nuclear devices, Russia, under President Vladimir Putin, was among the countries that did not censure it or impose sanctions. (According to some Russian commentary, in 1974, the Soviet Union had been informed in advance by India that it was going to test a nuclear device, and it tried hard to stop it. It also tried to get India to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.)

Still, bilateral relations did not thrive through the first decade of this century as India aligned its strategic objectives with the US and other Western nations, and importantly, diversified its arms purchases. In 2022, a year that has seen Putin go to war against Ukraine, creating massive shifts in geopolitical choices across the world, India is among the few countries that has remained “neutral” in a conflict that many trace right back to Gorbachev.