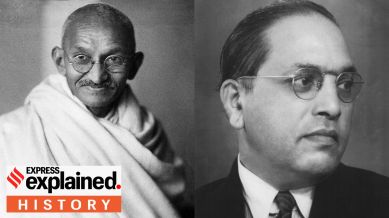

Why Ambedkar and Gandhi disagreed on question of separate electorates for Scheduled Castes

On September 20, 1932, Mahatma Gandhi began a fast unto death in Pune’s Yerawada Jail in protest against the award of separate electorates for Scheduled Castes

It was in this week in September 1932, at the Yerawada Central Jail in Pune, that Mahatma Gandhi began fasting unto death against the award of separate electorates to the Scheduled Castes.

The consequences of this fast, and the resultant Poona Pact between Gandhi and Dr B R Ambedkar, can be seen till date in the system of reservations that India has. Here is a recall.

Gandhi vs Ambedkar on caste

From being extremely orthodox to the point he supported prohibitions on inter-dining and inter-marriage, to later rejecting untouchability and referring to untouchables as harijans, Gandhi’s views on caste evolved over time.

However, his criticism of untouchability did not lead to him rejecting the institution of caste itself, which, as Ambedkar put it, would require Gandhi to reject the very basis behind caste — the Hindu religion. This is what made Ambedkar far more radical. Recognising that the legitimacy of caste is born out of the divine authority of the shastras (holy scriptures), Ambedkar said that no amount of piecemeal reformism that did not attack the authority of the scriptures themselves could undo caste.

Ambedkar’s political programme emphasised lower castes obtaining political power. “Nobody can remove your grievances as well as you can and you cannot remove them unless you get political power in your hands,” he wrote. He suggested separate electorates as a form of affirmative action to empower lower castes.

Ambedkar’s argument for separate electorates

“The depressed classes form a group by themselves which is distinct and separate … and, although they are included among the Hindus, they in no sense form an integral part of that community,” Ambedkar said during the plenary session of the First Round Table Conference in London. “The Depressed Classes feel that they will get no shred of political power unless the political machinery for the new constitution is of a special make,” he continued.

And what was this political machinery he was talking about? Separate electorates with double vote – one for SCs to vote for an SC candidate and the other for SCs to vote for in the general electorate.

He argued that while joint electorates might better help integrate lower castes into the Hindu fold, they would do little to challenge their subservient position. He believed that joint electorates “enabled the majority to influence the election of the representatives of the Dalits community, and thus disabled them for defending the interests of their oppression against the ‘tyranny of the majority’”.

Gandhi’s opposition to separate electorates

Gandhi’s opposition to separate electorates was ostensibly based on his view that they “do too little” for lower castes. Gandhi argued that rather than being restricted to just this measly share of seats, lower castes should aspire to rule “the kingdom of the whole world”. (Lower castes’ material and social condition meant that this was highly unlikely).

More importantly, Gandhi’s opposition also stemmed from the fear that separate electorates would “destroy Hinduism” by driving a wedge within the community. This was important for two strategic reasons.

First, Gandhi rightly understood how the British had exploited internal divisions in Indian society for their own purposes. According to him, separate electorates would only help the British ‘divide and rule’. Second, this was also a time when antagonism between Hindus and Muslims was rising. If separate electorates for lower castes were announced in addition to those for Muslims, this would significantly reduce the power that caste Hindu leadership enjoyed by breaking the consolidated Hindu fold.

Culmination of Gandhi-Ambedkar debate

The “Gandhi-Ambedkar debate” culminated with Gandhi’s fast which began on September 20, 1932. “This is a God-given opportunity that has come to me,” Gandhi said from his prison cell, “to offer my life as a final sacrifice to the downtrodden”.

Gandhi’s fast put Ambedkar in a tricky situation. He disagreed with Gandhi’s political alternative (reservations) which he believed would blunt possibilities for more radical social change. But given Gandhi was the nation’s most loved political leader, if something were to happen to him, the fledgling Dalit movement might bear heavy consequences — including the possibility of violence by upper castes.

With a heavy heart, Ambedkar succumbed to Gandhi’s pressure, inking the Poona Pact which secured reservations for Scheduled Castes but put the question of separate electorates to bed.

Many hailed Gandhi’s fast as victory against the British policy of “divide and rule”. As poet laureate Rabindranath Tagore said at the time: “it is worth sacrificing precious life for the sake of India’s unity and her integrity.”

For others, however, the fast was akin to coercion, with Gandhi leaving Ambedkar with no real choice. As Ambedkar would later ponder: “Why did he not undertake a fast unto death against untouchability?”

Ambedkar was never satisfied with this outcome. He would later write in What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables (1945), “The Joint Electorate is from the point of the Hindus to use a familiar phrase a “Rotten Borough” in which the Hindus get the right to nominate an untouchable to set nominally as a representative of the untouchables but really as a tool of the Hindus”.

This is an edited version of an article published last year.