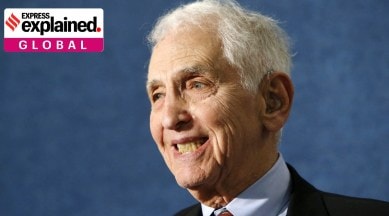

Daniel Ellsberg dies: How a US military analyst leaked the ‘Pentagon Papers’, revealing lies about the Vietnam War

His actions led to one of the most important Supreme Court cases for press freedom in the US in the modern era, set off a series of events that ultimately forced President Richard Nixon to reign, and accelerated the end of the Vietnam War.

Daniel Ellsberg, a US military analyst, who leaked the classified “Pentagon Papers” in 1971, revealing the doubts and deceptions of successive US governments about the Vietnam War, died on Friday (June 16). He was 92.

His actions led to one of the most important Supreme Court cases for press freedom in the US in the modern era, set off a series of events that ultimately forced President Richard Nixon to resign, and accelerated the end of the Vietnam War.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

“Daniel was a seeker of truth and a patriotic truth-teller, an anti-war activist, a beloved husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, a dear friend to many, and an inspiration to countless more. He will be dearly missed by all of us,” Ellsberg’s family said in a statement obtained by NPR, adding that the cause of his death was pancreatic cancer.

Early life

Born in Chicago on April 7, 1931, Ellsberg grew up in the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan. Although his mother wanted him to become a concert pianist and required him to practice many hours a day, Ellsberg didn’t have any interest in the musical instrument. He altogether stopped playing it two years after his mother and sister were killed when his father, a structural engineer, fell asleep at the wheel and crashed the car in 1946.

Ellsberg was a bright student from the beginning. He attended a prep school in suburban Detroit on scholarship and graduated first in his class. After earning a bachelor’s degree in economics, with high honours, from Harvard, he went on to receive a fellowship to study advanced economics at King’s College, Cambridge. Ellsberg subsequently returned to Harvard in 1953 for a master’s degree in economics.

A year later, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and earned a commission. According to The New York Times, “He saw no action, but he mustered out as a first lieutenant with firm ideas about military solutions to international problems.” In the following years, Ellsberg joined the RAND corporation — an American nonprofit global policy think tank and research institute — finished his doctorate and worked in the Pentagon and the State Department.

In 1965, Ellsberg was sent to Vietnam by the State Department to evaluate civilian pacification programs as the US became more involved in the South Asian country. The NYT reported that he stayed there for the next 18 months, accompanying combat patrols into the jungles and villages.

Change of heart

It was during his stay in Vietnam that Ellsberg realized the futility of the American war against Vietnam. In his 2003 book, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, he said “he was only one week into a two-year tour of duty in Saigon when he realized the United States was in a war it would not win.,” Reuters mentioned in its report.

After his return to the US, he and 35 other Pentagon officials were commissioned in 1967 to secretly put together a history of the Vietnam conflict. The 7,000-page report was completed two years later and came to be known as the Pentagon Papers. Ellsberg was deeply disturbed by the conclusions of the report — it revealed several American Presidents not only had lied about the extent of the US involvement in Vietnam but they had also been aware of the fact that the country was unlikely to win the battle.

Moved by the anti-war movement going on across the nation, Ellsberg began to oppose the conflict openly and later resigned from RAND, where he had resumed working after his return from Vietnam. He then approached Anthony J Russo Jr, his RAND colleague, and together they decided to photocopy the 47-volume Pentagon Papers.

Leaking the Pentagon Papers

As NYT reported, Ellsberg initially thought he “could work from within the system” and gave partial copies of Pentagon Papers to Senator J William Fulbright, the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and others in Congress. However, nothing changed.

Ellsberg then finally reached out to a veteran NYT reporter, Neil Sheehan, who he had first met during his visit to Vietnam. In March 1971, Sheehan spent the night at Ellsberg’s house in Washington and both men made a deal — if Ellsberg gave the papers to Sheehan and if the NYT decided to publish them, the reporter and the newspaper would do everything to protect the source’s identity.

But things didn’t go down as planned. When Sheehan went to the house of Ellsberg in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he had stashed the documents, Ellsberg refused to hand them over to him.

“He told Mr Sheehan he could read them but make no copies — because, as Mr Sheehan described it, “once he turned loose of it, The Times would assume ownership of it, and they’d do what they wanted with it.,”” NYT reported.

Although Sheehan agreed to not make any copies of the papers, he reneged on his promise after Ellsberg gave him the keys to his apartment and left the town. Believing the documents were “the property of the people”, the reporter made their copies and went to New York, where a team of reporters and editors from NYT began working to publish them at the earliest.

Aftermath

The newspaper published the first instalment of the Pentagon Papers on June 13, 1971, in response to which the Nixon administration obtained a federal court injunction, forcing NYT to cease publication after three articles. The President and his aides argued that printing the documents posed a threat to national security and was punishable under the Espionage Act.

As the showdown between NYT and the government ensued, Ellsberg, who had gone underground by then, leaked the papers to other publications such as The Washington Post.

“While eluding a major nationwide FBI manhunt, they (Ellsberg and his wife) kept outmanoeuvring the White House. On June 18, the Washington Post began publishing excerpts from a copy Ellsberg had smuggled to them. As soon as the Post was enjoined, excerpts began appearing in the Boston Globe. And then the Chicago Sun-Times. Next the St Louis Post-Dispatch. As soon as one paper was enjoined, another would start publishing until 17 newspapers got into the action.,” a report in The Nation magazine said.

Both NYT and Washington Post moved the Supreme Court regarding the matter and on June 30, the apex court ruled that the press had the right to publish the papers. Known as “New York Times Co. v. United States”, the case established that unless a national emergency, the press shouldn’t be subject to pre-publication censorship.

Two days before the ruling, Ellsberg had publicly admitted to leaking the Pentagon Papers. He and his former colleague, Russo, were charged with espionage, conspiracy and other crimes. But they were eventually set free by a court in 1973 after the “judge dismissed all the charges on the grounds of government misconduct.,” NYT reported.

It was found that G Gordon Liddy and E Howard Hunt, part of the White House’s “plumber” unit, had broken into Ellsberg’s former psychiatrist’s office in a bid to find incriminating information against him. Moreover, the FBI had illegally wiretapped Ellsberg’s conversations and there were attempts to bribe the judge presiding over the case.

Subsequently, it also came to light that Liddy and Hunt were also involved in the Watergate burglary, which ultimately led to Nixon’s resignation.

Ellsberg recently gave an interview to Politico regarding his role in leaking the documents. When asked if whistleblowing is worth the risk, he said: “When we’re facing a pretty ultimate catastrophe. When we’re on the edge of blowing up the world over Crimea or Taiwan or Bakhmut”.

“From the point of view of a civilization and the survival of eight or nine billion people, when everything is at stake, can it be worth even a small chance of having a small effect?” he said. “The answer is: Of course… You can even say it’s obligatory.”