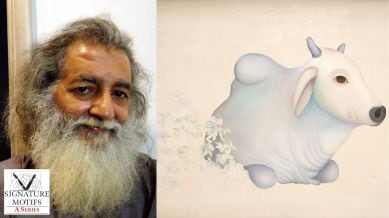

Empathy for animals, power of observation: Behind Manjit Bawa’s bovines symbolism

Man and nature, for Bawa, were meant to be in unison. At times, his depictions of bovines belonged to the mythical realm, while on other occasions, they appeared as enduring symbols of humankind’s resilience.

(This is the final instalment of a series on Indian masters and the motifs that appear repeatedly in their works.)

Drawing from Indian mythology, folklore, and Sufism, artist Manjit Bawa envisioned a world where humans and animals lived in peaceful harmony.

“He had deep empathy for animals… Completely at ease around them, he would fearlessly approach cows and bulls, and pat them affectionately,” Ina Puri, curator and author of Bawa’s biography In Black and White (2017), told The Indian Express. “His gentleness and familiarity with animals was reflected in his work, and brought a certain level of expertise that can never come from looking at them from a distance,” she said.

In particular, Bawa was fond of bovines: cows, buffaloes, bulls, and calves.

Manjit Bawa’s Childhood inspirations

“I grew up like Krishna, playing with [cows] and drinking milk straight from their udder… therefore, farm animals like cows… keep appearing in my paintings,” Bawa had said in a 2004 interview.

Bawa’s affinity for cows can literally be traced to his birth: the youngest of five brothers, he was born in a goshala (cow shed) in Dhuri, a small town in Punjab’s Sangrur district. He grew up in a family which cared deeply for animals. Puri said, “He often spoke about going for a walk with a cow or playing with cattle as they bathed in the stream”.

Man and nature, for Bawa, were meant to be in unison.

“All living beings in existence were linked with one another through love and integration of identities… His drawings sought commonality through the physical forms he created… Bull humps and a man’s knees could not help but have identical curves through the same principle of inter-connectivity,” art restorer and author Rupika Chawla wrote in a 2022 essay for the website of the Vadehra Art Gallery.

Evolving depiction

While studying fine arts at Delhi Polytechnic in the late 1950s, Bawa would spend hours observing horses in tabelas (stables) and in shelters where tongawalas retired for the night, Puri recalled. These experiences saw him experiment with figurative depictions in gestural brushwork.

Over time, more populated narratives gradually gave way to solitary subjects as Bawa’s visual language evolved. Instead of the then dominant greys and browns in Indian art, he began opting for more traditional Indian colours such as pinks, reds and violet.

“Until the mid-1980s, Bawa’s work featured numerous studies and drawings born out of his close observation of the figures and modest modeling. The animals mostly appeared alongside human figures in the narrative scenes,” Manoj Mansukhani, Director Marketing, AstaGuru Auction House, told The Indian Express.

“This changed in the mid-1980s and 1990s, when the colours deepened and the bovine motif became more central, as we saw in several of his Krishna-and-cow pairings,” he said.

Over the years, Bawa’s figures acquired a sense of weightlessness, as their perfectly rounded forms were portrayed in graded tones, with subtle chiaroscuro defined by the interplay of light and shadow.

“By the late 1990s-2000s, singular bovines dominated, defined by minimal lines and saturated backgrounds. There were no landscapes as the figures were surrounded by solid colour fields, giving them a heightened sense of divinity. Towards the end, we saw more silhouettes in a softer palette,” Mansukhani said.

Many meanings

“Bawa wanted his works to be open to diverse interpretations,” Puri said. At times, his depictions belonged to the mythical realm, while on other occasions, they appeared as enduring symbols of humankind’s resilience. Bawa, who himself had learned to play the flute from maestro Pannalal Ghosh, could himself be the flautist in his paintings, most often identified as Krishna, Puri noted.

A 1992 untitled painting featuring Krishna fetched a staggering Rs 25.11 crore at an AstaGuru auction in 2023. In 2017, Christie’s had sold Bawa’s 1998 Untitled (Krishna and Cow) for $780,500.

In another celebrated 1980 oil on canvas, Krishna eating the fire, the deity is seen encircled by a herd of cows and bulls as he literally swallows flaming fire.

In 2021, a Bawa canvas went viral after appearing in a Diwali photograph from actor Amitabh Bachchan’s home. Painted against a blue backdrop, the canvas had a solitary bull as an emblem of power and resilience. “The creatures he painted are his — distilled through his imagination, with the sweeping lines of their contours adding a certain vigour and power,” Puri said.