Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories

Postcards From The Past: ‘Verandah’ cases, medical internships in Pune that paid Rs 200 and a snake that came with a patient

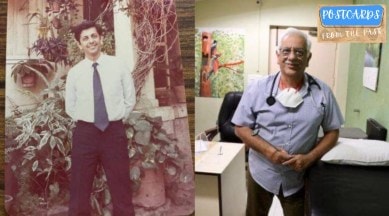

One of Pune's veteran doctors, Dr Nasli R Ichaporia, goes down memory lane to recall days when a night out in the city meant a trip to West End cinema and getting a 'sada dosa' at Deccan's Poonam Hotel.

As a post-graduate resident doctor in Pune in the late 1970s, Dr Nasli R Ichaporia was used to working long hours. Once, over a single night, he provided treatment to around 200 patients who had consumed spurious liquor. However, nothing prepared him for what happened one evening at Sassoon General Hospital’s medicine ward. It was not the laboured breathing and severe pain of a snake-bite patient that startled him, but a relative who had rushed in with the snake itself.

“There were small puncture wounds and the man was writhing in pain. But was it a venomous or non-venomous snake bite? I knew it would take at least 15 minutes to reach home where I had a book on reptiles. There was no internet, no functional computers or telemedicine facilities,” he says.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Luckily, at the same time, a young man was trying to set an unusual record by staying 72 hours with 72 venomous snakes inside a glass enclosure at BJ Medical College ground in Pune. Neelim Kumar Khaire, who eventually set a world record, was the best bet to identify the snake, Dr Ichaporia felt. “The ground was just five minutes away from Sassoon Hospital. I kickstarted my Yezdi motorcycle, told the relative to hop on with the snake, went straight to the ground, knocked on the glass cabin, and asked Khaire to identify the snake. “‘This is a krait,’ he said,” recalls Dr Ichaporia.

“The patient eventually recovered and was sent home,” says the 67-year-old with a laugh, and adding that he now plans to narrate the anecdote at the function which will be held this year to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1973 batch of BJ Medical College.

Today, Dr Ichaporia is the Director of Neurology at Sahyadri Superspeciality Hospital on Nagar Road. He has made a mark as a pioneer in thrombolysis for stroke in India, having done the first such treatment and later setting up the first stroke unit in the city. He is also well-known as a public speaker in the field of stroke and neurology, and has conducted more than 300 public lectures and workshops. He lives in Pune with his wife.

“Things did change after the 1980s but at that point, private medical care was non-existent in the city,” Dr Ichaporia recounts. “The best equipment and teachers then were at Sassoon General Hospital. Along with Armed Forces Medical College, these were the two government-run healthcare facilities in Pune. Sassoon had the best ultrasound machine and amazing clinicians and teachers who were devoted to both patient care and mentoring students… The quality of clinicians was top class and I still remember, the best doctors would come to Sassoon and teach for an honorarium of Rs 100 or Rs 200.”

‘It was all a jungle then’

According to him, Pune city was then “localised” between the Mula and Mutha rivers, and the Peth areas. Dr Ichaporia, who used to stay in Koregaon Park, remembers how the “newspaper-wallah” and the milkman would be scared to go beyond the Ghorpuri railway track. “It was a godforsaken place… Localities like Kothrud, Aundh, Kalyaninagar, Wanowrie and Nagar Road came up later but it was all a jungle then,” he says.

As for the medical college, “it was a tough grind and as resident doctors, we were on call 24×7. The little time we got for a night out was spent with other resident doctors at the West End cinema and getting a sada dosa all the way at Deccan’s Poonam Hotel. Latif’s and Kwality for continental and Punjabi food were a must.”

Not that it mattered, he says, because he would not have been able to afford it. “We hardly earned anything and my first salary was Rs 225 when I was engaged in an internship at the Cantonment Hospital in 1978. I would spend Rs 50 on petrol and an occasional visit to the cinema hall or the famous food joints then.”

“There were no pagers or mobile phones. For instance, if doctors watching a movie were required at Sassoon, the stand-in doctor at the hospital would call the cinema hall and ask for a message to be flashed on the screen. More often than not, we were called,” he adds.

One incident that Dr Ichaporia recollects was in 1978 when around 200 patients were brought to Sassoon Hospital in a serious condition after they had consumed spurious alcohol. “The ward had only one phone and 50 patients. Now, to alert the others meant getting through to the telephone operator who would then ask me to wait as the line was busy. That night was an unforgettable experience as the staff prepared floor beds. It was like a railway platform and the only treatment was to give them ethyl alcohol as that is an antidote for spurious liquor. The doctors ordered bottles of McDowell’s No.1 and treated them,” he explains.

Equipment lacking then, trust now

In those days, there were very few drugs and limited scope of treatment, particularly in the field of neurology, Dr Ichaporia points out. “There was very little knowledge then unlike today when the internet has changed the level of patient awareness. I went to study at NIMHANS (in Bengaluru) despite a few experts cautioning me that it was a dead field. There was no CT Scan, no nerve test. Sadly, a patient of stroke was referred to as a ‘verandah case’ and we were told to keep the person in the corridor of the hospital as there was not much we could do,” he recalls.

Today, Ichaporia says, such ‘verandah cases’ are treated in the emergency section and given therapy to restore blood flow to affected regions in the brain. “Alzheimer’s was not being picked up then… I am now seeing almost one every day and two patients with multiple sclerosis every week.”

There were very few ventilators at the hospital. “Often the patient’s relative was educated on how to use an ambu bag – a self-inflating resuscitator. This is a handheld tool that helps deliver pressure ventilation to a patient with insufficient breathing. What is easily available now was a rarity in those days. There were no pre-packed saline bags and no disposable syringes, either,” he says.

What the veteran doctor misses though is the “trust factor” in patients. “Then, the patients were a trusting lot and there was tremendous respect for the medical fraternity. There is so much anger today and people have become intolerant. Public expectations from senior doctors are sky-high and though we want to do our best every single time, it may not be possible every time. Breaking bad news to family members is always difficult but the truth must be said every single time, however bitter and painful. These were skills we learned on the job.”

According to him, celebrity patients are often difficult to manage. “The best patients I love the most are the poor,” he says, remembering how they would bring in a sack of potatoes, broccoli or even garlic as a mark of their respect and affection.

Dr Ichaporia says he has kept abreast with modern technology and the latest developments in the field of medicine, and teaches extensively via Zoom as he feels there is no substitute for passion and hard work. “Our intellectual abilities can be preserved till the late 70s,” says the veteran, who continues his practice.

The signboard at the doctor’s clinic sums it all up: “Good things happen to people who wait. So please do not jump your turn.”

Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories