With The Education of Yuri, Jerry Pinto has proved, yet again, that he is one of the finest chroniclers of a Bombay gone by

The writer's uncanny ability to put his characters through intricate trials and tribulations makes them jump off the page as living, breathing individuals

The Education of Yuri is the first book I sit down to read as I move into a new house in New Delhi. I seem to have brought the Bombay monsoons with me, and the constant clatter of raindrops falling on a tin terrace next door provides the perfect setting to embark upon Jerry Pinto’s sometimes awkward, often funny — but always moving — coming-of-age novel set in Bombay in the 1980s.

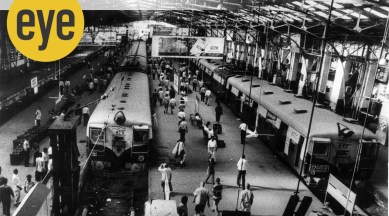

If you have read Pinto’s earlier works, The Education of Yuri offers a comfortingly familiar assortment of characters who clumsily navigate life in the big city. Surrounding our college-going, khadi langot-wearing, aspiring poet Yuri Fonseca is an array of peculiar Bombaywallas: Tio Julio and Mumtaz, Bhavna and Arif, Luigi and Muzzumil. On first encounter, each one appears almost caricatural. They drink country liquor on terraces of abandoned buildings in Breach Candy, flirt with Naxalism in secret meetings at nondescript libraries, watch rock musical Tommy in elegant Colaba flats, and ponder the meaning of love between Mahalaxmi and Churchgate station. What sets them apart is Pinto’s uncanny ability to put them through intricate trials and tribulations, which draws them out into making unexpected decisions and make his characters jump off the page as living, breathing individuals.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Early on, you realise that the novel’s protagonist isn’t Yuri but Bombay itself. “The British city looked back at them out of a hundred blind windows, encased in Malad stone,” writes Pinto, as he describes a city in transition. Yuri forges unusual friendships on Bullet rides between Bandra and Fort, plods along the hallowed steps of the Jehangir Art Gallery, and meets his future mentee within the cramped confines of a relief camp in Bhiwandi. Yet, this isn’t mere nostalgia: Pinto’s depiction of Bombay is characterised by an exceptional alienating affection for a home that one has struggled to claim as their own.

There is a part urgent, part indulgent urge to fervently document the rapidly disappearing institutions that have shaped his own adolescence. Coffees at Samovar and Cafe Naaz become quiet homages to experiences that now exist only in their storied descriptions. Yuri ambles from one bookstore to another. At the New and Second-hand Book Centre, he picks up Eunice De Souza’s Fix. From the venerable Mr Shanbhag at Strand Book Stall, he gets himself a copy of Nissim Ezekiel’s Hymns in Darkness, at a “thirty percent discount.” As verses from the assortment of books he collects rattle by in quick succession, I am grateful for the copy of Jeet Thayil’s magisterial Penguin Book of Indian Poets sitting by my bedside table.

For a Bombay boy who has grown up in the warm afterglow of the heyday of the city’s bustling literary scene, this is a delicious — almost voyeuristic — peek into another era from one of its last remaining interlocutors. After all, most of the stalwarts who graced the hallowed corridors of Elphinstone College are now dead. The delightful Soonu Kapadia, cheekily named Soonu Goradia in the novel, who was my own English teacher and instilled in me an enduring love for Tennessee Williams and John Donne, for instance, passed away less than a year ago. But as she exchanges ridiculous quips of “away you three-inch fool” and “poisonous bunch-backed companion” with the daunting Mehroo Jussawalla in the staffroom, I can almost see the twinkle in her eyes glimmer through the pages.

With The Education of Yuri, Jerry Pinto has proved — yet again — that he is one of the finest chroniclers of a Bombay gone by. Very few novels, after all, have the ability to command an almost unflinching loyalty so soon after the last page has been turned. I am ready to forgive Yuri’s tortured verses, telling myself that we have all once written from a place of teenage angst. I am even ready to overlook his often tedious quest to understand his own sexuality with a passing dash of annoyance.

There’s an almost familial familiarity as I give the book pride of place in a newly purchased bookshelf that now takes up an entire wall in my bedroom. The rains have stopped, but I know that I now have a little window that will let me breathe in a Bombay I want, one day, to claim as my own.

Anish Gawande is a writer and a translator. He is the director of the Dara Shikoh Fellowship in India and the curator of Pink List India, the country’s first archive of politicians supporting LGBTQIA+ rights