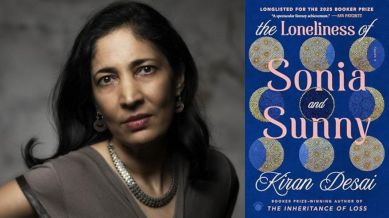

‘Fame is another kind of loneliness’: Kiran Desai on her Booker-shortlisted novel

The writer, 54, on her new novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, what she has learned about fame from her mother Anita Desai, and on being back in the Booker reckoning

For nearly two decades after her Booker Prize-winning second novel The Inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai disappeared into the long, slow work of writing and giving shape to her next book. The result is The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny (Penguin Hamish Hamilton), a novel shaped by the weight of migration, the ache of distance, and the quiet clarity of solitude. In this interview over Zoom from her New York home, Desai traces the story’s origins to her own college days in Vermont, her diasporic childhood, and the literary inheritance from her parents. As she re-emerges in the public eye, she speaks about fame, family, and the strange, private labour of making art in a noisy world. Edited excerpts:

What set you off on The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny?

The idea of modern-day loneliness. I had the idea of constructing the story through the lens of a long, unresolved love story. But as I took it into a sort of Indian love story — out in the world of the Indian diaspora — I realised that I could extend the story to look at many different kinds of loneliness, not just the romantic kind. And I decided to look at the divisions between countries, race, and gender through this idea of loneliness.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

What has been your own relationship with loneliness?

I’m actually reaching back to my own experience as a college student — being alone during winters and summers, because at that time, my mother was teaching one semester only in the States. She would teach one term and go back to India for the rest of the year, where my sister was still at home. The boys (Desai is one of four siblings) had left by that time. And so I was often by myself during breaks, like so many foreign students in those days. There was a phone booth in the dormitory, you could go and wait for your parents to call, but it was not easy to telephone from India in those days. So, there was real loneliness. But I knew I wanted to be a writer when I was in college, so there was also the exquisite artistic loneliness and the realisation that solitude is very wonderful if you want to write, if you’re an artist of any kind.

Give us a sense of the childhood that you had. How did it shape your life as a writer?

I think of how much my grandparents meant to me in terms of my work, and I am quite surprised now, because we would take a train to Allahabad once a year and I didn’t actually know them that well. Perhaps it’s the mystery of the grandparents also that takes me back over and over to that landscape. I found myself doing that, even in The Inheritance of Loss. The mystery of my mother’s parents haunts me. Imagine a German woman coming to India in the 1920s and settling down here. My mother is a product of these two very different cultures. She’s a real mix of Europe and Bengal. So I always had the great fortune of her vision of this duality, and of her bookshelves.

And I had the great gift of my father (Ashvin Desai) staying on in India — although my mother left to teach — so I didn’t lose India. My father was a big reader; he loved music and art. He taught himself how to read Urdu. He was a businessman with four children. There was no inherited fortune on either side of the family. My memory of him is of an extraordinarily hard worker. Then when he retired, he wrote a book called Between Eternities. He was reading until the last year of his life, visiting bookstores. So the music and the poetry in this book is due to him.

At a time when we are fighting against the fragmentation of attention, were you ever wracked by doubt while you were working on the book for two decades?

I was just focused on the art. I didn’t even notice the years going by. It was a shock to me that it was New Year’s Day again, or that it was my birthday again. I think that was the only time I felt nervous and thought, ‘Oh, goodness, the years are passing’. I remember when I turned 50. I thought, what’s happening? Am I just still working on this book? And the end was still a distance away. I’m lucky in my editors. It’s just extraordinary that publishers would wait and not put pressure on an author in today’s world where book publishing is a business. But they never treated it that way. I also had the great fortune of having a mother who was willing to read the draft.

And now you are on the brink of the Booker shortlist. What is your relationship with fame?

Fame is another kind of loneliness, a sense of self-displacement. It’s taken me 20 years to write this, and that has been very helpful in rooting myself in my work. To think of different kinds of artists — the kind who seeks fame, and the kind who wants to vanish into his or her or their work. So, yes, it is very strange to be in the public eye. I have to remember the skills that I learned after The Inheritance of Loss, because I have lost those skills and now I have to remember how to do this again.

What have you learned from your mother (writer Anita Desai) about living in the public eye?

She grew up in a world where there was not the opportunity to publicise your work in this way. It was a quiet world, a quiet life. She’s absolutely shocked to see what has happened. Celebrity culture being extended to writers seems like an absurd idea to her.

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com