Earth’s ozone layer is on track to recover completely in four decades

According to a UN-backed report created by an international body of experts, the Earth's ozone layer is on track to completely recover within four decades.

The Earth’s ozone layer is on track to recover completely within the next four decades thanks to the global phaseout of ozone-depleting chemicals. A UN-backed panel of experts confirmed this in research presented at the American Meteorological Society’s 103rd annual meeting on Monday.

According to the Scientific Assessment Panel to the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances quadrennial report, if current ozone conservation policies remain in place, the ozone layer should recover to values before the appearance of the ozone hole by around 2066 over the Antarctic, 2025 over the Arctic and by 2040 for the rest of the world.

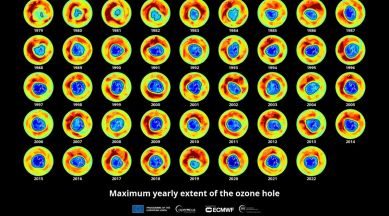

Meteorological conditions have been driving variations in the size of the Antarctic ozone hole but it has been slowly improving in area and depth since the year 2000.

This assessment was based on extensive studies, research and data compiled by a large international body of experts that includes members from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and European Commission.

What is the ozone layer?

Ozone is a molecule that is made up of three oxygen atoms. A layer of ozone sits in the stratosphere of our planet between 15 kilometres and 30 kilometres above the Earth. This layer absorbs a portion of the radiation from the Sun, preventing it from reaching our planet. Most importantly, it prevents a portion of UV light called UVB from reaching the surface of the Earth and harming us and all living things.

What is the ozone hole?

At any given time, ozone molecules are constantly formed and destroyed in the stratosphere. Without human intervention, the total amount of ozone in the ozone layer should remain constant over time. But the ozone molecules in the atmosphere get destroyed when they come in contact with bromine and chlorine atoms. In fact, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, one chlorine atom can destroy over 100,000 ozone molecules before it is removed from the stratosphere.

Some compounds, called ozone-depleting substances, release chlorine or bromine when they are exposed to intense UV radiation in the stratosphere. The use of these compounds leads to ozone molecules being destroyed faster than they are being created. The rampant use of such compounds eventually led to the formation of a hole in the ozone layer. Over time, this lack of ozone protection can potentially lead to damaged crops and increased risks of skin cancer and cataract for exposed populations.

How did we work to fix the Ozone hole?

World government came together to stop the depletion of the ozone layer with the Montreal Protocol, which was designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out many ozone-depleting substances. Currently, 198 nations, including all United Nations members have ratified the treaty and outlawed the use of many ozone-depleting substances.

This resolution was so successful that in 2003, then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan referred to the Montreal Protocol as “perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.” The latest quadrennial report reaffirms the positive impact that the treaty has had on mitigating the damage done to the ozone layer.