When Nehru was criticised for attending Queen Elizabeth’s coronation

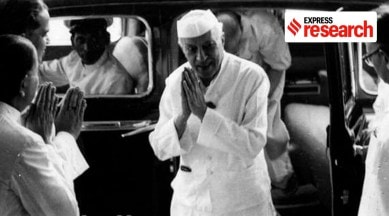

The last coronation of an English sovereign took place in 1953, just a few years after India gained independence from the British. Amongst the many dignitaries that attended the function was India's Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru who expressed his awe of the proceedings in a televised interview with the BBC. However, Nehru's attendance elicited criticism at home, with many Indians questioning why he would legitimise the occasion.

From bottles of gin and tins of biscuits to street and garden parties; and from pork pies and quiches to souvenirs and memorabilia — the UK is ready to celebrate King Charles III’s coronation.

A landmark affair, Charles’ coronation will be attended by several world leaders, diplomats, humanitarians, and members of the Royal family. Vice President Jagdeep Dhankar will represent India at the ceremonial event.

Almost 70 years ago — on June 2, 1953 — it was former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru who represented India, when the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II took place. Nehru not only attended the festivities but also marked the occasion with his first televised interview, conducted with the UK’s national broadcaster, the BBC. Speaking about the event, Nehru, much impressed by the “spectacle”, praised the “orderly London crowds and the way they behaved.”

Nehru courted criticism at home for his decision to attend the coronation soon after India had freed itself from British rule. When asked during the BBC interview if there would be no criticism in India about him coming to the coronation, Nehru said there would be, but that it would not amount to anything.

The Delhi Durbars

By 1953, when Queen Elizabeth was crowned, India was no stranger to the coronation celebrations and had hosted three Delhi durbars — in 1877, 1903, and 1911 — each marked by a grand political spectacle.

These durbars were held at Coronation Park, located nearly 17 kilometres away from Connaught Place, in New Delhi.

In 1858, the blame for the mutiny that had occurred just one year previously fell sorely at the feet of the East India Company. In response to the growing discontent, authority over India was passed from the Company to the Crown following the passage of the Government of India Act by the British Parliament.

Although the Crown took control of India in 1858, it wouldn’t be until 1876 that the Queen of England was officially introduced to her Indian subjects. Upon urging from her Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, Queen Victoria added the moniker, Empress of India, to her many lauded titles. To mark the occasion, the English Civil Servant Thomas Henry Thornton organised a mass celebration that would signify the transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown.

Although Queen Victoria did not attend the celebrations, her proclamation as India’s new sovereign was read aloud to a muted gathering of Indian subjects. In it, she promised Indians that under her rule, the principles of liberty, equity and justice would prevail, adding that she wished sincerely for the health and happiness of her new subjects.

According to a report by the US Library of Congress, Queen Victoria’s proclamation resonated deeply with Indians, that many Indian rulers got up and cheered, praying for her long life and enduring prosperity.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Despite her popularity at the time, Queen Victoria’s durbar was devoid of much of the grandeur displayed at the coronation of her successor, King Edward VII in 1902. According to a report in The Times of India, King Edward’s coronation was celebrated across India, masterminded by the Viceroy of India at the time, Lord Curzon.

Under Curzon’s meticulous guidance, the durbar was a “dazzling display of pomp, power and split-second timing,” according to Stephen Bottomore, a filmmaker who captured the event. Amongst the many celebrations issued in his honour, the coronation of King Edward transformed Delhi into a tent city, featuring not only a temporary railway for the masses of crowds, but also a variety of specially designed stores, post offices, hospitals, and police stations.

By contrast, the 1911 coronation of King George V was considerably less splendid, despite the fact that the King and his Queen consort were the first British monarchs to set foot in India for the occasion. In anticipation of their arrival, Bombay constructed the now magnificent Gateway of India (although at the time, due to delay in construction, a temporary structure was forced to suffice), and the royal visit was marked by celebrations spanning several cities and adoring crowds.

However, the most historically relevant feature of this durbar was not the monumental celebrations themselves but the lone act of defiance by one Indian Prince that would serve as the precursor to the Indian Independence movement.

During the 1911 durbar, each Indian prince was expected to perform a ceremonial act of loyalty towards the King by bowing three times in front of him before backing away without turning. As documented by the biographer Jessica Douglas-Home, whose grandmother, Lilah Wingfield, attended the event, the Gaekwar of Baroda, in a noteworthy display of disobedience, bowed improperly and then turned his back towards the King.

Nearly half a century later, this act was personified by a myriad of Indians, who, under the stewardship of Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, would successfully agitate for independence from British rule. However, only six years after Independence, Nehru would invite criticism by attending the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Nehru, Queen’s coronation, and the BBC interview

By the time Queen Elizabeth ascended the throne in 1953, India was not only an independent republic, but one that had shed the shackles of British rule by joining the Commonwealth of Nations only upon the condition that she would be free from swearing allegiance to the Crown.

Nehru, a prominent architect of these developments, therefore shocked many when he decided to attend the coronation of the new reigning monarch of India’s former colonisers. Much of the blame and accusations levied upon Nehru were due to his association with the anglicised Indian elite, as documented by the Indian historian B R Nanda in the Journal of Modern Asian Studies.

Coming from “one of the most anglicised families in India,” Nanda writes, Nehru was born into a life devoid of nationalist orthodoxy, featuring instead, English “table manners, customs, and systems of education.” Nehru was tutored by an English governess and was sent to boarding school and later, university in England. However, even in his depths of anglicised life, Nehru felt the “stirrings of an ardent patriotism,” according to Nanda.

Nehru was a member of an association of Indian students at Cambridge that clamoured for independence, rejected British Dominion status as a member of the Indian National Congress, and called for the withdrawal of all British forces from India. According to the private secretary of the Viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, who met Nehru in 1931, the future Prime Minister of India was “intractable, uncompromising and determined to work for complete independence.”

However, as Nanda goes on to narrate, Nehru would soon compromise his stance towards the British, justifying his acceptance of the modified Commonwealth as a way of preventing “further disruption”. Nehru reportedly told noted American economist, John Kenneth Galbraith, “You realise, Galbraith, that I am the last Englishman to rule in India.”

In 1953, when Queen Elizabeth was crowned, an approximate 30 million people watched the event on TV with over 11 million more following it on the radio. The coronation of King Charles III is expected to draw in around 300 million people, many of whom reside outside of the United Kingdom. Despite that, Charles has opted for a much smaller affair, inviting only 2,000 guests as opposed to roughly 8,000 guests who were invited to attend the Queen’s coronation ceremony.

Amongst the attendees, Nehru was joined by the prime ministers of Myanmar (formerly Burma) and Pakistan, along with former US Secretary of State, George Marshall, and Colonel Anastasio Somoza of Nicaragua. However, none of their presence stirred up the kind of controversy that Nehru’s visit generated.

Nehru, however, remained unfazed by it all. When asked in the BBC interview if there would be no criticism in India about him coming to the coronation, Nehru said: “There was when I came and there will be no doubt when I go back, but I don’t think it’ll amount to much.”

On being asked why he, and by extension the Indian people, were so quick to forgive the British, Nehru said: “Well, partly we don’t, I suppose, hate for long or intensively.” This, he noted, was the legacy left behind in India by Mahatma Gandhi.