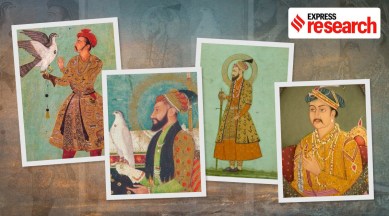

How Akbar and Aurangzeb have contrasting images in India and Pakistan

Akbar and Aurangzeb were both great Mughal rulers, but their legacies have been shaped not only by their achievements but also religious and nationalist politics that swept across India in the centuries to follow. Akbar, a secular Muslim is glorified in India and denigrated in Pakistan, whereas Aurangzeb, known for his piety has been resigned to the opposite fate

The study of history plays a crucial role in the nation-building process. This is particularly true for newly-established and post-colonial countries such as India and Pakistan. Both countries share a common past, but were born out of a violent Partition based on religion. The understanding of history in both these countries, thereafter, evolved in contrasting terms. This is best witnessed in the way both countries provide a diametrically opposite characterisation of two of the biggest rulers of Mughal dynasty — Akbar and Aurangzeb.

In Indian textbooks and popular imagination, Akbar is often framed as a just and tolerant leader, a Muslim who put the country and people over faith. Meanwhile, his great grandson Aurangzeb is portrayed as the catalyst for the demise of the Mughal empire.

Historian Ian Copland in A History of State and Religion in India (2013) writes that the “difficulty with such a binary approach is that it oversimplifies what are in fact extremely complex issues.” Copland argues that while religion did play a significant role in the lives of South Asians during Mughal rule, the perception of its significance today is influenced by the religious and nationalist politics that succeeded it.

To understand those politics, we must first understand why the criticism of Aurangzeb is frequently collocated with the exoneration of Akbar.

Akbar on religion

The recorded secularism of Akbar is rooted in his policy of sulh-i-kul or universal harmony. First articulated by the mystic thinker Sufi Ibn Arabi in the 12th century, the concept posits that kings are bound to a certain social contract with their subjects which permits the practice of any faith, given that all religions are a pathway to God.

Following that philosophy, Akbar was known to be tolerant and respectful of all religious beliefs, codifying that tolerance into action and policy. In 1564, when he was just 22 years old, Akbar abolished jizya, the controversial, albeit common, punitive tax against Hindus. He also prohibited the slaughter of cows, ordered a translation of the Vedas, Mahabharata and Ramayana into Persian, and, to the disdain of Sunni clerics, permitted Shias to offer their version of namaz at court.

While remaining a pious Muslim, Akbar was also known to drink Ganga water and was the first Mughal ruler to marry into a Rajput family.

So revolutionary was Akbar’s religious permissiveness, that by the end of his life, Hindus believed him to be an orthodox Muslim and Muslims believed him to be a Hindu convert.

However, Akbar was not without his missteps, chief of which was ordering a massacre of civilians after the Siege of Chittorgarh, possibly to fortify his Muslim credentials amongst Central Asian nobles, says historian Parvati Sharma in an interview with The Indian Express. Eventually though, Sharma says, Akbar was moderated by time and experience, and became a man who allowed complete freedom of religion across his kingdom.

As the late scholar Nazid Ahmed writes in the Encyclopedia of Islam, “Akbar was a universal man; he was more than any single group thought of him… (and was) the purest representation of that folk Islam that grew up in Asia after the destruction wrought by the Mongols.”

The reign of Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb’s religious policies are hotly debated amongst historians. Some, like Jadunath Sarkar, consider him to have been an orthodox bigot, while others, like Shibli Naumani, argue that his motives were political rather than religious. The former for example, claims in his book, A Short History of Aurangzeb, that the late Mughal ruler wanted to establish ‘Dar-ul-Islam’, a complete Islamic state in India in which all dissenters were to be executed. On the other hand, Naumani, in his book, Aurangzeb Alamgir Par Ek Nazar, writes that “Aurangzeb’s zeal for Islam was that of a politician rather than a saint”.

What cannot be debated, however, is Aurangzeb’s own devotion to Islam, which was evident from, as Bengali poet Malay Roy Chaudhury writes in a comprehensive paper about Hindu-Muslim relations, the “iconoclastic zeal” he displayed as a prince. After his second coronation in 1659, Aurangzeb issued orders forbidding practices like drinking, gambling, and prostitution in adherence with his Muslim faith. He also abolished a number of taxes that were not authorised by Islamic law, and, to compensate for the lost revenue, reimposed the jizya tax on non-Muslims.

Aurangzeb’s orthodoxy can be explained in part by his upbringings and complex rise to power. During Shah Jahan’s reign, there was a protracted struggle for power between Aurangzeb and his three brothers, most notably Dara Shikoh. Dara, who advocated publicly for harmony between Muslims and Hindus, was the heir apparent, favoured by his father to accede to the throne.

In order to usurp the line of succession, Aurangzeb battled fiercely with his brothers, eventually sentencing all three to death and confining his father to a gilded prison for the last seven years of his life. According to Copland, these brutal events put into question the legitimacy of Aurangzeb’s rule, prompting him to enact policies that would appease the influential ulama, whose support he desperately needed to retain power.

Audrey Truschke, historian and associate professor of South Asian history at Rutgers University, notes that Aurangzeb’s puritanical nature was driven by a need to distinguish himself from Dara and was more a by-product of politics, not religion.

Historians are also divided on the factual aspects of Aurangzeb’s rule. As per popular understanding, under Aurgangzeb’s reign several Hindu temples were destroyed in the course of the 18th century. However, historian Richard Eaton, author of Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India, claims that just over a dozen temples were destroyed under Aurangzeb, with even fewer tied to the emperor’s direct commands. Copland, for his part, asserts that Aurangzeb built more temples than he destroyed.

Additionally, while some studies claim that Hindus were barred from official service during this time, other studies show that there were more Hindu officers under Aurangzeb than under any other Mughal Emperor.

These contrasting views are unlikely to ever be definitively resolved, especially given that the accounts provided by Aurangzeb’s court historians, Khafi Khan and Saqi Khan, are subject to considerable scrutiny. As both their sources were written years after the Emperor’s death, in The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King, Truschke alleges that they relied on memory and heresy to reconstruct events, “allowing unintentional errors to creep into their chronicles.”

Understanding Akbar and Aurangzeb in India and Pakistan

Indian historians position Akbar as the exemplar of a just and tolerant Muslim leader, with popular films like Jodha Akbar even celebrating the love between the Emperor and his Hindu wife. In contrast, Aurangzeb is blamed for his supposed cruelty against non-Muslims, his influences on modern day jihadis, and his role in the collapse of the Mughal empire which set the stage for British colonial rule.

This depiction of Aurangzeb, and the larger Mughal Empire, was articulated by the British in the early days of colonial rule. Alexander Dow, Scottish orientalist and writer, in his 1772 book The History of Hindostan writes that “the faith of Mahommed is peculiarly calculated for despotism; and it is one of the greatest causes which must fix for ever the duration of that species of government in the East.” For him, and other colonial era thinkers, the solution to this despotism was the imposition of British command over India. While Indian nationalist leaders vehemently rejected the solution, many retained the fundamental characterisation.

In his book, Discovery of India, Jawaharlal Nehru described Aurangzeb as a “bigot and an austere puritan,” who functioned “more as a Moslem than an Indian ruler”. More than 70 years later, that narrative has not changed. In 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about Aurangzeb’s “atrocities” and “fanaticism” at an event in Varanasi. In April 2022, on the birth anniversary of Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur, Modi said the Sikh Guru stood “like a rock” in front of “Aurangzeb’s tyrannical thinking.” Guru Tegh Bahadur was beheaded on the orders of Aurangzeb for refusing to convert to Islam.

In Pakistan, however, Aurangzeb is considered to be the personification of an ideal Muslim leader, a notion exemplified by his militarism, personal deference to Islam, and willingness to weave Islamic morality within his empire’s social fabric.

Allama Iqbal, a politician and philosopher who was a leading advocate for the Pakistani state, saw Aurangzeb as a nationalist and “the founder of Musalman nationality in India”. Influential political leaders such as Maulana Abul Ala Maududi praised Aurangzeb for his commitment to Islam, calling for his morals to pave the way for Pakistan’s political future.

In Pakistani textbooks, Akbar, not Aurangzeb is accused of fermenting the downfall of the Mughal empire. Ali in his article writes that the contrast between the two “appears a conflict between evil and good, and Akbar suffers a humiliating defeat in the hands of textbook historians”.

According to Ali, in Pakistani educational curricula, Akbar is not mentioned directly but indirectly as a rival of Ahmad Sirhandi, a Sufi scholar. Ali quotes one Pakistani textbook that states, “Ahmad Sirhandi, a great Muslim saint and scholar who challenged the might of Akbar to revive and re-establish the glory of Islam in the subcontinent.”

The idea that Akbar was not a devout Muslim is rooted in his policy of Din-e-Ilahi, which loosely combines aspects of different religions including Islam, Catholicism and Jainism. Although there is no evidence that Akbar attempted to promote this ideology amongst his subjects (its adherents were numbered at roughly 19 during his reign), Din-e-Ilahi is used by his critics as proof of his vision to distort Islam by combining it with other religions.

Ali writes that the arguments to accuse Akbar for the downfall of the Mughal Empire is derived from the Pakistani historian I H Quershi, who vehemently criticises Akbar’s incorporation of non-Muslims in the Mughal Empire. “Akbar had changed the nature of the polity profoundly,” wrote Quershi as cited by Ali. “The Muslims were still the dominant group in the state, but it had ceased to be a Muslim state… Akbar had so weakened Islam through his policies that it could not be restored to its dominant position in the affairs of the State,” Quershi wrote.

Akbar’s policies towards the Rajputs were particularly criticised by the historians in Pakistan. Sheikh Muhammad Raqif in Tarikh-i-Pakistan-wa-Hind (1992) writes “he favoured the Rajput so much so that his nobles had lost confidence in him. They regarded the Mughal rule no more Islamic.”

Some authors, like M Ikram Rabbani, even blame Akbar’s secularism for the division of Hindus and Muslims, claiming it to be the reason behind the origin of the two-nation theory.

On the other hand, Aurangzeb is seen as a vanguard of Islam, a projection of the man that is as influenced by nationalist politics as is his negative characterisation in India. As historian Ayesha Jalal writes in Conjuring Pakistan: History as an Official Imagining (1995),“Pakistan, with its artificially demarcated frontiers and desperate quest for an officially sanctioned Islamic identity, lends itself remarkably well to an examination of the nexus between power and bigotry in creative imaginings of national identity.”

However, it is also worth noting that Aurangzeb’s legacy in Pakistan is not absolute. According to a report by the Brookings Institute, the conflict between Aurangzeb and his brother Dara mirrors the struggle for national identity today. The former represents the religious fundamentalists who denounce non-Muslims and the latter, the moderates who believe in tolerance and diversity.

The report also states that Dara and his liberal interpretation of Islam is little known outside the circles of the educated elite whereas Aurangzeb’s purported views are far more mainstream. General Zia ul-Huq, who “seeded the extremism of today’s Pakistan with his severe, authoritarian version of Islam,” was heavily inspired by Aurangzeb, and since his time, the Mughal emperor’s image lines the walls of many government offices.

Akbar and Aurangzeb were both Muslims. Both rulers of a vast and powerful empire. Both capable of acts of horror and acts of grace. Both hated by some and loved by others. Their actions, and public religiosity, rather than being seen in the context of their time and of their varying political landscapes, is reduced to an overly simplified personification of Hindus versus Muslims and India versus Pakistan.