Ear to the Camera

A new film on blind photographers,Light on the Dark Side,challenges the basic premise of photography that one needs vision to take good pictures.

A new film on blind photographers,Light on the Dark Side,challenges the basic premise of photography that one needs vision to take good pictures.

Theres one image in photographer Mahesh Umrranias album that he cherishes above all others. It is a picture of a shadow of a tree on a pavement,with the leaves and branches creating an interplay of shade and sunlight. In one corner,two pairs of legs walk out of the frame take away this element,and this picture becomes less striking. I took the image by judging the temperatures of the sun and shade, says Umrrania,the legs entered the frame by accident,an accident that would not have happened if I were not blind. Umrrania is that oxymoron called a blind photographer. And,as a new short film,Light on the Dark Side,reveals,India has a small but proud community of such visually challenged sharpshooters.

With her filmmaker husband Avinash Singh,Geeta entered the dark world of blind photographers with one firm rule her film would not patronise her subjects. As it turned out,she neednt have worried. Umrrania cockily defined blindness for her: Blindness means no need of light. You have constant light all the time,that is never broken by darkness.

Light on the Dark Side zeroes in on a movement begun in 2006 by Partho Bhowmick,founder of Blind with Camera blindwithcamera.org,which teaches shooting techniques to the sightless through workshops conducted across the country. Umrrania was the first student. Over the phone from Mumbai,where he works as an IT manager,Bhowmick says,In 2004,I came across the works of a blind Parisian photographer. My curiosity led me to contact him and Art beyond Sight,a New York-based art education institute for the blind. Over the next two years,I carried out independent research into artwork by the blind and,after I had learnt enough,I started Blind with Camera.

By the end of 2006,Bhowmick had 10 students. The following year,Blind with Camera held its first exhibition,at the National Centre for Performing Arts in Mumbai,and followed this up with many more an exhibition is on at the Harrington Street Arts Centre in Kolkata until September 21.

The film searches for an answer to the question,What can a blind person see? and provides a gallery of pictures showing pigeons in flight,peepal leaves bursting out of a white wall,coils of colourful ropes hanging in perfect symmetry,locked doors and long-distance shots of monuments. Each time I teach them,there is a stronger belief in me that there is sight at the core of darkness, says Bhowmick in the film. The group has sold several photographs,with 50 per cent of the proceeds going to the photographers. The images are priced between Rs 5,000 and Rs 12,000,depending on their size.

The first session in Bhowmicks workshop involves understanding a students visual perception how much they remember and relate to colours and expressions among others. Umrrania,for instance,lost his vision as a child and says that he does not remember facial expressions,while another student,Kanchan Pamnani,turned blind in her thirties. One of the questions I ask is whether they watch movies. The students generally describe a film in terms of sound,and use their imagination to fill in the blanks,which may not be the same as what is happening on the screen, says Bhowmick. He is also careful to make no promises of photography becoming a livelihood source to the students.

When cameras are first handed out,students are asked to run their hands over it and get to know its contours. The screen,they say,is smoother than the body of the camera,and of a different temperature. Next,we take them outdoors and pair a completely blind student and a low-vision student,and give them an hour to shoot whatever they choose. This is the exciting part because many of the students havent touched a camera before, says Bhowmick.

When the eye cannot see,the ear begins to hear. Blind photographers normally judge the composition and subject according to touch feeling a statue,for instance,and then stepping back to shoot the flutter of pigeons and,the toughest,temperature judging the intensity of light through heat. Their hearing and other senses are acutely developed to compensate for the lack of sight, says Geeta. Ravi Thakur,a blind photographer trained by Blind with Camera,shot a picture of a cyclist near the sea on the basis of sound. I was surprised to hear the sound of someone cycling from the sea side. I asked a sighted companion about it and then followed the sound of the cyclist to take his picture, he says.

Pamnani uses a pinhole camera to take images and one of her masterpieces is from a holiday in Goa where I was feeling calm as I was near water,away from the crowd and in a vast,open space. I felt on top of things. Her picture shows a railing at a distance,and is suffused with the idea of vast space. When I was a kid,I was quite into photography. I had low vision,so the results werent very flattering and we didnt have digital cameras in those days. I would imagine things that werent there,and didnt see what was there. Finally,somebody would say that I should let somebody else click pictures, says Pamnani,a Mumbai-based lawyer. Now a proud photographer,she says with a laugh that every creative stroke helps.

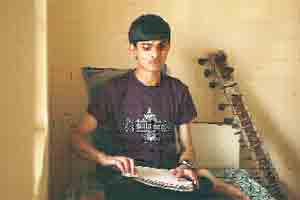

Umrrania,who belongs to a small village in Maharashtra and has a blind elder sister,says,We had so few amenities that a camera was not even something we thought of as children. It was when I got my first cellphone,with its screen reader software,that the world opened up for me. I could do anything make friends,stand a short distance away and take pictures. There was no technique,but I was excited. Now that he knows the techniques and rules of composition and framing,Umrrania is ready to fly I have to make it big, he says. When he is not shooting,Umrrania is an acupressure specialist and plays the sitar with a blind orchestra.

In the film,celebrity photographer Atul Kasbekar calls the collection of photographs nice images even if you do not consider the fact that the people who are shooting them are blind. But,how do blind photographers score in terms of photographys aesthetic rules? What rules? asks Geeta. When we say that this is how it should be,we are defining rules because we can see and create standards. Perfection is different for every person. As Umrrania would attest,even accidents can create masterpieces.