📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

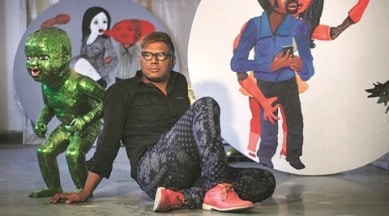

I’m a provocative artist: Artist Chintan Upadhyay builds a narrative around sexuality, the male gaze and gandi baat

Artist Chintan Upadhyay brings together his experiences in Delhi to build a larger narrative around sexuality, the male gaze and gandi baat.

Somewhere deep inside Khirki Extension in south Delhi, the road becomes narrower and bumpier before converging into Sheikh Sarai, a quieter neighbourhood. As the lane leads to a drab concrete-grey studio, a man, clad in pink pants and black button-down shirt, ushers us inside with a smile. The dimly lit room is dotted with canvases of doe-eyed figures, framed doodles and, in a far corner, distinct bronze sculptures of what appears to be cloned babies. It’s easy to spot artist Chintan Upadhyay’s signature works at a glance.

It’s been four years since the 43-year-old artist moved from Mumbai to Delhi. “I had some personal problems which were taking over my mind and space. I took a risk and came here with an absolutely empty mind,” says the artist, lighting a cigarette and settling into his chair.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

The city soon consumed him, with its sights, sounds and people. Mostly people. His first rented apartment in Green Park became a battleground for neighbours, who objected to a project wherein he invited people to work, spend time and create something new in his studio. He abandoned the project and moved to Sheikh Sarai. There, he faced ire from his new set of neighbours over a painting of a naked baby. “Yahan shareef log rehte hain (Decent people live here),” they told him, and proceeded to call the cops.

On less dramatic occasions, be it in the bustling Khirki or the choked Hauz Khas Village, he mulled over conversations, either overheard or narrated by friends. “I started recording them. I could see how technology has shaped new ideas, relationships and self-images. Some saw it as liberating, some suppressing. I was also amazed by how fast Delhi youngsters were changing and claiming the city. Ten years ago, it wasn’t so,” says Upadhyay. Real-life instances of this confidence, especially among women, and the resistance it has evoked among those immune to change, became all the more topical in these times of “bans and moral policing,” he says. As he broke away from his stylistic conventions, the artist became more and more engaged with a project that he fondly calls “Gandi Baat”. It’s a series of sketches, created over the last two years, which frames men, women and children in caricatures as they bring up subjects of sexuality, the aggressive (“very Delhi”) male gaze, and moral policing, among others. “Gandi Baat” is a direct reference to the abusive language and gestures that pervades the public space, be it the streets, social networking sites or films. “Abusive language has become the new aesthetic. Gandi baat has entered the public domain, but it is no longer taboo. It’s become cool,” says the artist.

Upadhyay’s sketches are designed to provoke: a woman holding on to a rail in a bus wipes a tear and says, “You are pervert”; a popcorn has the title Mard Popcorn (because he overheard a man tell his friend, “Mard popcorn jaise hone chahiye (A man should be like a popcorn)”. A teenager evaluates her nude self in front of the mirror and thinks, “I am small”. A plain paper holds a sketch of a woman and says “I am a drawing; Do I look pornographic?”

These are hurried doodles that employ acerbic, unrestrained language, often left incomplete for the viewers to form their own interpretations. They evoke visuals that are designed to either make you uncomfortable or smirk with familiarity. “And why not? I’m a provocative artist. If people don’t feel comfortable, that is their problem. But there are some complex issues in the society and I like to bring out those things,” says the artist.

Having traversed four major cities — Jaipur, Baroda, Mumbai and now Delhi — Upadhyay draws his stylistic and iconographic influences from each of them. In his hometown Partapur, Rajasthan, he saw his abstract artist-father constantly at odds with the traditional art and artists of the state. But this contradiction proved significant in his understanding of the arts. He dropped out of a BSc course and helped out in his father’s Jaipur studio, before moving to Baroda to pursue art. “We used to call it a sanskritik city. Yet, I saw it transforming into a violent one, a kind that was against culture too. My work The Mutants was a response to it,” he says. In Mumbai, popular culture made a big impression on him, as did the sounds from Bollywood. “Women in item songs became a provocative entity. Even the backdrop dancers became more Western,” he says.

Over the years, his “designer male babies” — fibre-glass sculptures of perfect but identical male babies — have echoed his mounting concern about female infanticide, man’s desire for perfection in an age of technology and bio-engineering, consumerism and the loss of innocence. “Even though I get my references from Delhi in this series, it really fits everywhere. In fact, there is a common theme running in all my works, no matter what the medium is,” he says.

His “cultural productions” of flagrant realities have often placed Upadhyay in a controversial position — from sitting nude for visitors to smear saffron on him, a comment on the 2002 Gujarat riots to creating phallus-shaped stuffed toys, to covering his classic baby sculptures with Kama Sutra imagery in miniature form. “Artists of all forms have been wrongfully placed on a pedestal. The moment you say art, it seems to move away from reality. It automatically adds value to it, whereas art can be part of routine life. When someone resists artistic expressions and attacks galleries and theatres, that is the only time when artists wake up,” he says.

Presently preparing to showcase “Gandi Baat” in Baroda’s Studio 10, followed by Jaipur in February 2016, Upadhyay is thinking of bringing it to Delhi too. “Of course, there will be interest from some people and a little criticism from others,” he says. Apart from the exhibition, the artist wants to keep the images for a book, which will be divided into three to four themes — “the neighbourhood, women who are progressive, women who feel/talk regressive, men and women in new forms of relationships, and anecdotes from the streets”. “It plays out everyday on the streets and somebody should talk about it. Instead of making people afraid of art, bring them into it,” says Upadhyay.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram