Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

After a journalist’s killing, how his story exposing corruption came to life

Moreno’s work was made easier by the lax regulatory climate that followed the 2016 Peace Accords — signed between the Colombian government and rebels — which made public money easily accessible in areas like Puerto Libertador that were particularly affected by the more than 50-year armed conflict.

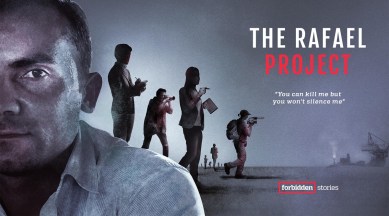

“If you have to kill me, kill me. But I am telling you to your face: you won’t silence me.”

It was with these words, spoken in a 37-minute Facebook live on July 21, 2022, that Colombian journalist Rafael Moreno defied his detractors and predicted his own demise.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

In the video, Moreno cites artificially inflated contracts, unfinished public works projects and companies profiting off rampant corruption and embezzlement.

Three weeks prior to posting the video, Moreno found an anonymous note on his motorcycle, accompanied by a bullet. Months later, on October 16, 2022, just after 7 pm, Moreno was closing his bar and grill when a man wearing a baseball cap came into the restaurant. The man took out a revolver and fired three times at Moreno, killing him instantly. The assassin is still on the loose.

Several days before his assassination, Moreno had been in contact with Forbidden Stories with the aim of joining the SafeBox Network, which allows threatened journalists to upload and protect their sensitive information. On October 7, 2022, Moreno started to share elements of the final investigation with the SafeBox Network team.

Through ground reporting, Moreno had discovered that dozens of trucks were being driven out to a river abutting a national park in Cordoba, where, he said, they pilfered sand for use in public construction projects. All of it was illegal, Moreno said.

In late September 2022, Moreno filmed himself, this time from what he believed to be the scene of the crime: a plot of land belonging to Carmen Aguas, the wife of Gabriel Calle, the patriarch of the Calle family – one of six families in the Cordoba area fighting over political influence.

In a statement to the consortium, Gabriel Calle Demoya denied all responsibility for the extraction of sand.

If the Calle family formed the basis of Moreno’s final investigation, the journalist’s white whale was another politician – Espedito Duque, who was, ironically, his mentor. Duque was elected in 2015 and Moreno came to work for the new mayor. In due course, he felt that the changes Duque had promised were slow to arrive. So, in December 2018, he made a career change, became a journalist, and launched Voces de Córdoba to investigate the excesses of the administration he once worked for. He started by analysing public contracts signed by Duque.

Moreno’s work was made easier by the lax regulatory climate that followed the 2016 Peace Accords — signed between the Colombian government and rebels — which made public money easily accessible in areas like Puerto Libertador that were particularly affected by the more than 50-year armed conflict.

In total, over $100 million has been invested in the five municipalities of the region since the accords. These were earmarked for use on more than 130 public works projects, including road repairs, education, and health care, as well as housing and energy infrastructure projects.

Moreno published his investigations on his Facebook page. But this type of reporting also led to threats from local armed groups. These groups regularly take a cut of the money invested into public works, a sort of keep-the-peace tax Moreno called “la vacuna,” or “the vaccine”. That year, Moreno was designated as a target by an organized crime faction called the Caparrapos. Two years later, he was briefly kidnapped and interrogated by members of the Gulf Clan, an armed group that shares territory with the Caparrapos.

In Moreno’s email inbox, the SafeBox Network discovered a key document: a formal administrative complaint he had filed against Espedito Duque and his cronies for “acts of corruption, embezzlement of public funds, influence trafficking and clientelism” on January 5, 2021. The 21-page alleges “various types of crimes against the public administration.” Moreno specifies the operative mechanism Duque put in place: creating “a certain number of structures” for his close friends and family and then contracting with them in order to “facilitate the appropriation of public resources.”

Among the dozens of NGOs Moreno named in the complaint were two linked to Duque. One, Serviexpress ATP SAS, was founded by an individual close to Duque’s wife, Julieth Arroyo Montiel. Another, Renacer IPS SAS, represented by the son of a government employee who worked for Duque, obtained two contracts worth more than $75,000 dollars.

As part of the Rafael Project, the Colombian investigative news outlet Cuestión Pública, which specialised in corruption and public abuse of power, and CLIP, a consortium of Latin American news outlets, picked up where Moreno left off. Their analysis shows that between 2016 and 2022, the Duque and Soto administrations signed 99 contracts with 13 businesspeople close to the Duque “clan,” contracts worth a combined $3 million dollars.

Of those, just five companies, some of which had no prior experience with public markets, won 96 per cent of the total value. The majority of these companies belong to Martín Montiel Mendoza, who is close to Espedito Duque. Between 2016 and 2022, the mayor’s office signed 56 contracts, more than half of them by mutual agreement – meaning a public offer was never opened – with three companies owned by Mendoza, for a total of just under $1 million dollars.

The first of these companies, Corporación Visión Juvenil, was formed as a nonprofit in 2014, just one and a half years before Duque’s election as mayor. As of this writing, the company has provided logistics solutions for sporting and cultural events, signing 36 contracts worth about $600,000 dollars. A second company, Innova Construcciones e Inmobiliaria, founded in 2017, signed four consecutive contracts with the mayor for managing parks, libraries and the municipal town hall. The first of these contracts was signed just 10 months after it was registered with the Chamber of Commerce. The third company, Serviexpress Colombia, was also created in 2017, and provides services including transport, advertising, human resources and assistance for elderly and handicapped people. Between 2019 and 2022, Serviexpress inked no fewer than 16 contracts for a total of $200,000 dollars, primarily for providing food and cleaning products to the mayor’s office.

Montiel Mendoza did not respond to multiple requests for comment sent by the consortium.

Cuestión Pública and CLIP also looked into the company that treats wastewater in Puerto Libertador, Agualcas. During a municipal plenary session, Moreno had identified a discrepancy between the number of streets with sewers in Puerto Libertador and the number shown in official maps released by the mayor’s office. Agualcas, which is supposed to furnish the infrastructure, nevertheless received various public contracts for installing sewers.

The consortium’s investigation revealed that this company, too, was under the influence of the Duque “clan.” In the years since his election as mayor, this company has been owned by three people close to Duque, all of whom worked on his election campaigns. During this period, Agualcas benefitted from 13 public contracts worth around $800,000 dollars. Agualcas did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Researching municipal contracts, Cuestión Pública and CLIP were also able to identify a presumed associate of the infamous Gulf Clan – one of the groups believed to have been involved in the kidnapping of Moreno — among Duque’s entourage.

For his part, Duque is allegedly thinking of running for election in Puerto Libertador this October. He did not respond to questions about his potential candidacy. Gabriel Calle Aguas, the son of the Calle “clan” Moreno had investigated, remains candidate for the regional governorship in those same elections. Only this time, the two are running without the sharp eyes of Rafael Moreno trained on them.