The story of one woman for whom Partition was a memory she lived with

Personal narratives by survivors have slowly begun to reveal the effects of Partition, including its psychiatric consequences

In the summer of 1947, when Chandana Dutta was 16 years old, she fled Dhaka. She packed one sari, a few books, and a sewing machine. She left to join her mother and sisters in Kolkata, 200 miles away, leaving behind her father, a proud professor at the University of Dhaka, who insisted on staying.

Religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims had been simmering in Dhaka and Kolkata for years, culminating in the bloody violence unleashed in 1946 -’47. When Dutta first arrived at the airport in Dhaka, she described seeing “black tar” on the grass outside, which she came to find out were, in fact, the dirt-covered bodies of migrants, who were camping outside the airport desperate for a ticket out of the country. In a miraculous gesture of generosity that changed her life, one of the migrants, out of pity, offered her an extra ticket to reach Kolkata.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

I am the granddaughter of a Partition migrant. In 1946, my great-grandmother, a widow, moved her family of four sons, including my grandfather, from Barisal to Kolkata. From the roof of his one-room tenement, he witnessed the extraordinary violence that erupted in the streets of Kolkata. Yet, he never spoke directly of the psychic effects of his displacement. I am also part of the Indian diaspora: My father moved to the United States in 1989, and I was born in Boston in 2005. By the time Partition entered my consciousness as a writer, my grandfather had passed away. I had no record of his displacement, or its manifold effects, on him, my father, my paternal family or on my own identity.

Despite the scale of this forced migration, it is only recently that micro-histories and personal narratives provided by survivors have begun to reveal the psychiatric effects of this mass displacement. Although largely neglected by historians and textbooks initially, these experiences and disorders have already found their voices in “colloquial” sources, such as literature, films and oral histories.

I sat down with Dutta in New York City in early November 2021 for what had intended to be a short interview. We ended up speaking for over an hour. Dutta was animated, and eager to tell her stories in detail and at length. Four months later, I got to know that Dutta, who was 89 years old, had passed away.

In her history of Partition, The Great Partition (Yale University Press, 2008), historian Yasmin Khan briefly suggests that many Partition survivors can be labelled as having either a “desire to forget” or a “desire to remember” their experience in the migration. A new “psychiatric history” of Partition is emerging that helps us understand this monumental migration not just in terms of broad political movements, but also through the personal and psychological testimonies and micro-histories of those who experienced it, such as Dutta’s.

“The desire to remember” enables a survivor’s trauma to be recognised and validated. This process of remembering is transformative: stories become vessels of healing. In its pathologic form, though, it can become obsessive and all-consuming, manifesting itself as psychiatric disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety. Conversely, the “desire to forget” arises from shame and stigma, where denying one’s traumas becomes a coping mechanism. Forced forgetfulness can kindle psychological repression that drives narcissism, dissociation, psychosis or addiction.

Dutta’s memories — her “desire to remember” — offered an intimate testimony of suffering, replete with classic symptoms of clinical depression, including loneliness, anhedonia, anxiety and social avoidance. As she remembered her childhood and adolescence, her voice broke down, softened in tone, and she was almost in tears. She told me in a quiet voice, “I still could hear my father sing a small tune… and I could still hear his voice, and then I struggled.”

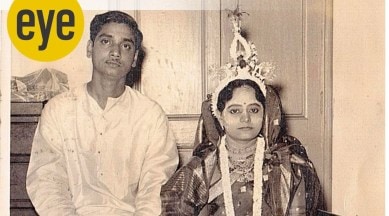

Dutta’s depression was exacerbated by her relationship with her non-migrant peers, who coined a cruel nickname for her: “SPGR” — or “specific gravity” — to signify the mental heaviness (gravity) in which she was always shrouded. Her depression finally abated when she married and started her own family in 1962, but she remembered her early years in Kolkata and Delhi as being among her most difficult.

Although remembering her childhood in Dhaka exacerbated Dutta’s depression, it was also an act of healing. Not all survivors are as eager as Dutta to share, or remember, their traumas. In contrast to those who suffered from depression and anxiety, there were others whose “desire to forget” became manifest in cognitive dissociative disorders, psychosis and addiction. Perhaps, the most vivid example of the “desire to forget” can be found in the work of the great Urdu writer Sadaat Hassan Manto, who migrated to Lahore, Pakistan, from pre-Partition India. Here, he fell into a deep depression, which progressed into restlessness, followed by disassociation, addiction, and frank psychosis.

Manto’s addiction spiralled further into a dissociative disorder characterised by the physical and mental “out of body” experience. As his biographers relate: “His drinking escalated. Signs of madness began to appear. He hallucinated, saw ghostly faces and talked nonsensically.” Unable to reconcile the rifts caused by Partition, Manto died in 1955 from alcoholism and likely hepatic failure.

This desire to forget on an individual level also has a larger collective corollary. Indian society, and the government, as a whole became a tacit participant in a form of collective denial and cognitive dissociation. Partition remains an uneasy part of India’s past because fully assimilating its trauma would inevitably mean complicating a cherished notion that anchors national identity: Indian independence. After decades of denial about the toll of mass displacement and violence, the memories of history have begun to let themselves out. Some of these oral histories are now being collected by historians and analysed by scholars and writers. As the granddaughter of a Partition survivor grappling with the intergenerational effects of this monumental event, a national project to document the oral (and psychiatric) histories of the slowly dwindling cohort of Partition survivors would yield a wealth of scholarship and reconciliation. We would remember so as not to forget.

(Leela Mukherjee-Sze is a Grade XII high school Senior at The Dalton High School in New York City)

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!