An elephantine day at Yala National Park

Travelling through Sri Lanka’s second-largest national park, which has been the cornerstone of the island nation’s wildlife

The sky yawns, and the sun rises from a recurring dream. Yala doesn’t have to wake up. It never sleeps. The calls of langurs, junglefowls and other emissaries of day fill up the morning. There is the Indian Ocean on one side, and on the other is the dominion of Panthera pardus kotiya: a thousand square kilometres of deciduous forests, shrubs, marshes, grassy plains, huge rock formations, silver lagoons and sandy beaches. The fingers of sea pull at the sand and waves dance like dervishes.

This second largest national park of Sri Lanka with the highest concentration of leopards in the world was saved because it was a hunting reserve, as most national parks in India once were. The Ceylon Game Protection Society (The Wildlife and Nature Protection Society now), formed by 26 hunters, was instrumental in establishing it. The park has been the cornerstone of the island nation’s wildlife. Every time you see it, it is as if you have never seen it. Gates open. Jeeps drive in. A dancing peacock doesn’t give us right of passage. Instead, he throws frantic colours in the morning air. Our camouflage jackets are not fooling him. But there are crucial things in hand like wooing his girl. A sloth bear tends to a wound on our mud-blown path. He doesn’t give a hoot to human hips jutting out of jeeps to catch a glimpse of his scrubby mane.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Other than the rock pools, streams and the two rivers, the ‘tanks’ made by the kings of yore provide water for the elephants. You can picture Adam naming the sheer variety of wildlife here—bee-eaters, jackals, elephants, crocodiles, mongooses, water buffaloes, sambar, wild boars… Seven endemic and several migratory birds swim and soar in Yala National Park. Here the migrants are not refugees. They claim it as their own, and the forest greets their yearly visits with endless conversations and banquets.

Afternoon. We come across a colony of the endemic grey hornbills by a lake. Couples take off in flight and plant kisses on beaks, tentatively, and then in a rush of emotion…telling each other that no one loves you like I do.

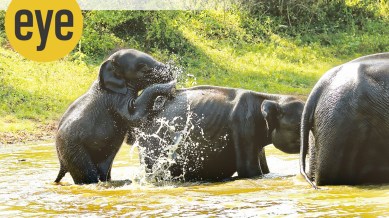

A herd of elephants walks swaying their tiny tails to a water hole. After fun and frolic, the mothers try to get the babies out, but one keeps running back into its bubble bath.

Later, a lady elephant in heat catches the side-handle of our jeep, her one angry eye looking into my partner Aditya’s two inches away. Half of the people in the jeep remember Almighty, till the driver gives her a poke. She moves ahead, giving us a look that she understands her own brute force as well as the limitations of the divine.

Evening falls. Lucas, the alpha leopard, makes jeeps jostle and jam as he comes out to have a leisurely evening drink. The jeeps wait, till the very last moment they can push their luck. And then speed furiously towards the closing park gates.

Dusk. We loosen our bones after a day-long adventure, with mud-caked hair, the forest on one side and ocean on the other. The sky catches the sun and puts the shiny coin in her pocket of countless suns. In the ink-night, the sea, loved by the moon, rises in a tide. I imagine I hear a whale song. It sneaks up on you, the awe of the primitive. Suddenly, sitting by the moon-washed mangroves, I feel the urge to get down on my knees and pray to the trees. To save themselves from us. “Don’t die,” I whisper. As if believing enough would make it happen.

The writer is a Colombo-based writer and environmentalist