An Ajmer court on Wednesday (November 27) admitted a petition by the Hindu Sena which claims that there lies a Shiva temple under the revered Ajmer Sharif dargah, and that an archaeological survey should be conducted to ascertain the same.

Beginning of spiritual journey

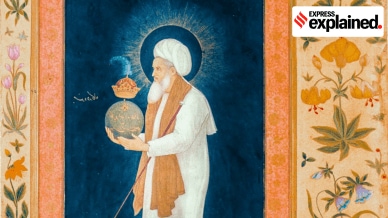

Moinuddin was born in 1141 CE in Sistan, a province in Persia (Iran) which borders present-day Afghanistan. He is said to have been a descendent of Prophet Muhmmad.

Orphaned at the age of 14, Moinuddin’s spiritual journey was set off by a chance encounter with Ibrahim Qandozi, a wandering mystic. While breaking bread with the old mystic, Moinuddin asked whether there was anything else to life apart from loneliness, death and destruction. Qandozi replied in the affirmative but said that “each human being must make an effort to discover and to experience this truth for himself”. (Mehru Jaffer, The Book of Muinuddin Chishti, 2008).

This set the young man on a path of self-discovery and spirituality. By the age of 20, Moinuddin had travelled far and wide studying theology, grammar, philosophy, ethics, and religion in seminaries at Bukhara and Samarkand.

His journey eventually led him to Khwaja Usman Harooni, a revered Sufi master of the Chishti order, near Herat (present day Afghanistan). In Khwaja Usman, Moinuddin found a mentor, undergoing years of rigorous spiritual discipline under his guidance. He was ultimately initiated into the Chishti silsila (chain of spiritual descent), after which his mentor left and set Moinuddin on his own path.

Becoming Ajmer’s Garib Nawaz

While travelling in Afghanistan, Moinuddin eventually accepted Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki as his first follower. With Qutubuddin, he moved to Multan where he stayed for around five years, studying Sanskrit and talking to Hindu scholars, and then to Lahore, where he meditated at the shrine of scholar Ali Hujwiri.

Story continues below this ad

From Lahore, Moinuddin travelled to Delhi and then Ajmer, the capital of the Chauhan kingdom. He was around 50 when he reached Ajmer (sometime in 1191, according to Jaffer). While many say that the city was at its peak under the rule of Prithviraj III during this time, the era of Chauhans in what is now North India was soon going to come to a bloody end.

After losing to the Muhammad of Ghor in the Second Battle of Tarain (present-day Haryana) in 1192, the Chauhan dynasty’s rule came to an end. The Muhammad of Ghor’s armies went on a murderous rampage, sacking the Chauhan capital and leaving behind a trail of suffering in its wake.

Seeing the suffering in Ajmer, Moinuddin decided to stay on and help the city’s people. With his wife, Bibi Ummatulla who he met in Ajmer, he built a mud hut in the city, and began to serve the needy. “The modest home of Bibi and Muinuddin made of mud soon became a refuge for all those without roof, shelter or food, and for those seeking solace and peace. His generosity and amazing acts of selflessness earned Muinuddin the title of Gharib Nawaz, or friend of the poor,” Jaffer wrote.

For instance, “… for the homeless a large langarkhana, or open kitchen, was supervised by Bibi. Here every human being irrespective of religion or status was welcomed and fed,” she wrote.

Story continues below this ad

Moinuddin interacted with Hindu sages and mystics as well, noting how much he had in common with these people who, like him, were unafraid to express their utter devotion to their creator, and rejected the orthodoxy of the clergy. His teaching, emphasising on equality, divine love, and serving humanity transcended sectarian boundaries at a time when the subcontinent underwent Islamic conquest, and witnessed significant political upheaval.

A transcendental legacy

Sufism emerged between the seventh and 10th centuries CE as a counterweight to the increasing worldliness of the expanding Muslim community. Sufis embraced a more ascetic and devotional form of Islam, and often engaged in a variety of mystical practices. Eventually, Sufi practitioners came to be organised in various orders which congregated around the teachings of a certain teacher or wali.

The Chishti order was founded in the 10th century by Abu Ishaq Shami in the town of Chisht near Herat. But it was Moinuddin and his disciples who led to its spread in the subcontinent.

Among his most prominent disciples was Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki (1173-1235), who established the Chishti order base in Delhi. Kaki became a central figure in the region’s spiritual life as the spiritual guru of Iltutmish, the third Sultan of Delhi. The Qutub Minar is said to be named after Kaki, whose shrine lies in Mehrauli, next to the iconic structure.

Story continues below this ad

Kaki’s disciple Baba Fariduddin (1173-1265) spread the Chishti order’s teachings in Punjab. Baba Farid was given the name Ganj Shakr or ‘a treasure of sweetness’, by Moinuddin. Other notable disciples included Hamiduddin Nagauri, who served as a spiritual leader in Nagaur.

Nizamuddin Auliya (1238-1325), whose teachings and shrine in Delhi are celebrated to this day, and his successor Chirag Dehalvi (1274-1356) carried on Moinuddin’s message well after Moinuddin’s passing in 1236.

And the Chishti order’s influence can be seen in the patronage it received from rulers throughout history. Among the Mughal emperors, Akbar in particular is said to have revered Moinuddin. He made several pilgrimages to the shrine, beautified Moinuddin’s mausoleum, and helped revive the city of Ajmer.

“Pilgrimage to the shrine by members of the [Mughal] royal family made Ajmer so popular that the rich and powerful soon crowded the town with more mosques, covered courts and countless guesthouses,” Jaffer wrote.

Story continues below this ad

Khwaja Moinuddin’s teachings continue to resonate in India today. His emphasis on love, compassion, and inclusivity resonated deeply in a region that is religiously diverse. And his integration of Indian cultural practices into Islamic spirituality helped bridge the gap between communities.