When humans started using tools: the theories and the evidence

For a long time, tool technology was seen as a uniquely human trait, associated with the genus ‘Homo’. Now we know tools go much further back in history.

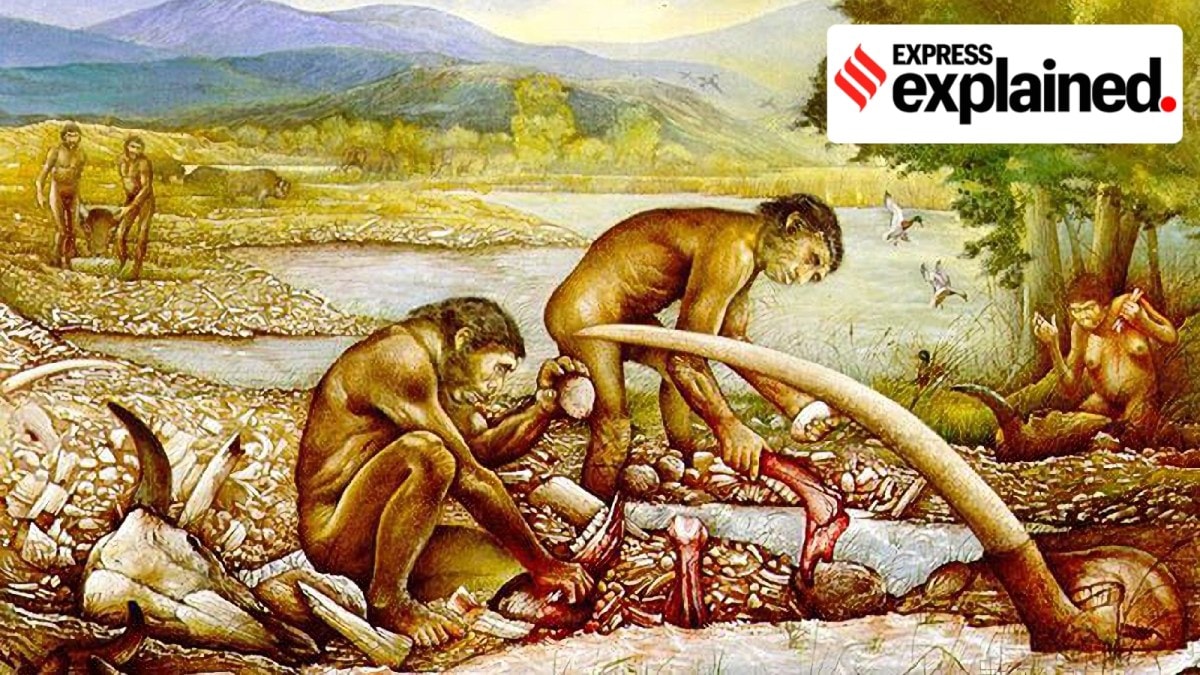

Our ancient ancestors were using bone tools at least 1.5 million years ago, roughly a million years earlier than was previously thought, a study published last week in the journal Nature reported.

The earliest known stone tools are even older, dating to 3.3 million years ago. These dates are based on prehistoric tools that have survived into the present. Our ancestors were likely using wooden tools just as long ago, although none have endured the vagaries of time. The earliest evidence for the use of wood dates back to only 700,000 years ago.

‘Man, the tool-maker’

British palaeoanthropologist Kenneth Oakley in the late 1940s identified tool-use and toolmaking as uniquely human traits which implied “a marked capacity for conceptual thought”.

In his influential book, Man the Tool-Maker (1949), Oakley wrote: “The real difference between what we choose to call an ape and what we call man is one of mental capacity.”

While Oakley acknowledged that other species may also use things in nature as tools, he said that “to conceive the idea of shaping a stone or stick for use in an imagined future eventuality is beyond the mental capacity of any known apes”.

Oakley’s theory that tool technology was a uniquely human trait held ground for several decades.

In 1964, British-Kenyan palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey and his colleagues proposed that a collection of roughly 1.7 million-years-old fossils discovered at the Olduvai Gorge (present-day Tanzania) belonged to a new species within our own genus. He named this species Homo habilis, or the “handy/able man”, due to its presumed ability to make tools.

This assessment was based on the discovery of certain cranial bones which indicated a large brain size, hand bones that indicated dexterity needed for toolmaking, and an assortment of stone tools that were found at the site. Notably, Leakey insisted that these fossils belonged to the genus Homo because toolmaking was a uniquely human trait.

Other primates & tools

But evidence from the natural world suggests otherwise.

Charles Darwin had noted that chimpanzees, our closest extant relatives, used what may be referred to as tools. He wrote in The Descent of Man (1871) that “the chimpanzee in a state of nature cracks a native fruit, somewhat like a walnut, with a stone.”

Darwin’s thesis was expanded by the pioneering primatologist Jane Goodall in the 1960s. She found that chimps were not only adept at using objects in nature as tools — sticks to fish for termites, leaves to drink water — but also occasionally modified these in order to serve a specific purpose.

But if chimps could use, and (to an extent) make tools, tool-use and toolmaking were not uniquely human traits, as was believed at the time. Primate studies carried out in the following decades have only supported these findings.

Researchers have now documented chimps coming up with rudimentary wooden spears, and capuchin monkeys of South America (unintentionally) producing stone flakes that were identical to those produced by our ancestors while crafting tools.

Lucy’s grippy hands

Despite Goodall’s findings, scientists for decades continued to hold an anthropocentric view of tool technology.

This is why, when palaeoanthropologist Donald Johanson in 1974 discovered Lucy, the partial skeleton of a 3.2-million-year-old human ancestor of the small-brained species Australopithecus afarensis, he did not give much thought to whether or not she was a tool user.

At the time, tool technology was still considered unique to Homo, and Lucy predated the earliest available stone tools by more than 1.5 million years.

It was Mary Marzke’s 1983 work on the morphology of Lucy’s hand bones that changed everything — although not immediately. Marzke concluded, according to an article in the Scientific American, that “the types of grips that Lucy and her kind may have used…could [enable it to] manipulate stone tools” to perform tasks such as cutting meat with stone flakes or smashing bones to extract nutrient-rich marrow.

Marzke’s thesis was confirmed by archaeological evidence in 2010, when a team of researchers in Ethiopia found “bones bearing unambiguous evidence of stone tool use — cut marks made while carving meat off the bone and percussion marks created while breaking the bones open to extract marrow”. (‘Evidence for Stone-Tool-Assisted Consumption of Animal Tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia’, published in Nature).

Five years later, another team found a cache of crude stone tools in Lomekwi, Kenya, dated to 3.3 million years ago — the oldest stone tools available till date.

Ditching ‘human exceptionalism’

The works of Goodall and Marzke challenge what scholars today refer to as “human exceptionalism”, that is, the idea that humans are different, superior to all other species in the world.

The theory that tool-use and toolmaking are uniquely human traits stuck around for so long because of our belief that we are special, despite ample evidence around us suggesting otherwise.

For instance, the study of other primates has shown that a number of hand morphologies — not just that of humans — are capable of highly dexterous behaviours.

So where does this leave the history of tool technology? It is impossible to pin an exact date, but the latest evidence based on the analysis of living primates suggests that even “the last common ancestor of all great apes some 13 million years ago had precision dexterity and used tools,” the article in the Scientific American said.