This Quote Means: ‘The present system of govt is destructive and despotic to Indians and un-British and suicidal to Britain’

On July 6, 1892, Dadabhai Naoroji was elected to the British House of Commons. We discuss an excerpt from his book 'Poverty and Un-British Rule in India (1902). Quotes from historical figures are an integral part of the UPSC CSE syllabus.

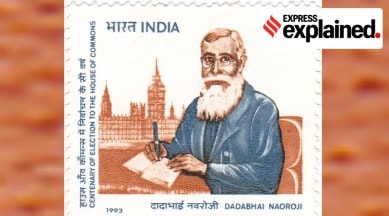

Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), fondly remembered as the “Grand Old Man of India”, was the first Indian to become a member of the British Parliament, elected to the House of Commons on July 6, 1892.

A staunch critic of British rule in India, his scholarly work uncovered the immense economic exploitation of India under the British. The “drain theory” argued that through their rule, the British were draining India of her resources, leading to the nation’s continued impoverishment. According to him, India was paying “tribute” to Great Britain for something that did not directly bring any profit to the country.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Dadabhai Naoroji also served for three terms as the president of the Indian National Congress – from 1886 to 1887, then from 1893 to 1894 and finally, from 1906 to 1907. He was highly respected by many later, more prominent figures of the Indian national movement, such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Madan Mohan Malviya and Mahatma Gandhi. Notably, in his book Hind Swaraj (1909), Gandhi even referred to Naoroji as “the author of nationalism” and “the Father of the Nation”.

“Had not the Grand Old Man of India prepared the soil, our young men could not have even spoken about Home Rule,” Gandhi wrote.

Today, we discuss an excerpt from Poverty and Un-British Rule in India (1901), which gives a glimpse of Naorji’s politics and economic understanding. Quotes from historical figures and those involved in India’s anti-colonial struggle are an integral part of the UPSC CSE syllabus.

The quote

Dadabhai Naoroji summed up his ideas in the introduction of Poverty and Un-British Rule in India.

“In the present system of government is destructive and despotic to the Indians and un-British and suicidal to Britain,” Naoroji explained, “On the other hand, a truly British course can and will certainly be vastly beneficent both to Britain and India.”

These lines encapsulate both Naoroji’s economic critique of British rule in India, as well as his reformist position. Like moderates of his era, he did not ask for “independence” as we understand the term today. Rather, he believed in the possibility of “just” British rule in which Indians would have a say in their own governance – hence benefitting both natives and colonial rulers.

We further break this down.

The drain of wealth and despotic rule

Shashi Tharoor quipped in his famous 2015 Oxford Union speech, “Colonialists like Robert Clive bought their rotten boroughs in England on the proceeds of their loot in India, while taking the Hindi word loot into their dictionary as well as their habits.”

Today, the discussion of the drain of wealth from India under British rule is fairly mainstream. But, one of the first to make the argument and substantiate it with numbers was Dadabhai Naoroji.

In Poverty and Un-British Rule in India, Naoroji, quoting English politician Sir George Wingate, argued that “when the taxes are not spent in the country from which they are raised… They constitute… an absolute loss and extinction of the whole amount withdrawn from the taxed country… might as well be thrown into the sea”.

This extraction, through highly exploitative revenue collection practices, was at the heart of the destitution faced by India’s masses involved in agriculture “Famines and plagues like the present are fast bleeding the masses to death,” Naoroji wrote.

Moreover, he pointed to how British conquest in India was not only “fought mainly with Indian blood, but every farthing of expenditure… by which the Empire has been built… has been exacted from the Indian people.”

These arguments were substantiated in Poverty and Un-British Rule with data. According to Naoroji, over the course of British rule in the country (at the time of writing), India had lost at least 200 to 300 million pounds, which could have otherwise been invested towards the betterment of Indians themselves.

This was, according to Naoroji, because Indians had absolutely no say in the administration of their own country. Not only unjust on principle – “no taxation without representation” being a basic democratic maxim – but this drove the drain of wealth from India and drove the country to impoverishment.

“ … the people of India have not the slightest voice in the expenditure of the revenue, and therefore in the good government of the country,” Naoroji wrote.

Un-British rule, doomed to perish

While making some strong criticisms of the British, Naoroji stopped short of calling for complete independence. In fact, the prism he was viewing the situation from was very much one which looked at the Empire as a possible force of good.

Naoroji commended the “humane influence” of the British on India, pointing to things such as the abolition of sati, the benefits of English education, as well as advantages of the British legal system. His criticism, thus, came from a position where he felt that the extractive nature of Britain’s colonial enterprise in India was in direct contradiction with political ideals cherished by the British themselves. This is what made British rule so “Un-British”.

“We have not fulfilled our duty or the promises and engagements which we have made,” Naoroji wrote, quoting the Duke of Argyll, who was the Secretary of State for India from 1868 to 1874.

Moreover, this “Un-British rule” was also deeply damaging to Britain. Naoroji argued that the way things were being run, there was absolutely no possibility for British rule to ever be popular among Indians. This, he predicted, would ultimately lead to the Empire’s downfall. “And if the British rule remains, as it is at present, a heavy yoke of the stranger… it is doomed to perish. Evil is not, and never will be, eternal,” Naoroji wrote.

The alternative: “True” British rule

Naoroji wrote Poverty and Un-British Rule in India not for Indians, but for Britons. He hoped that his book would be able to show the British the injustice and damage caused under the present system of governance, and in turn, usher in reform such that British rule would be beneficial for “both Britain and India.”

“My whole object in all my writings is to impress upon the British People… there is a great and glorious future for Britain and India … if the British people will awaken to their duty, will be true to their British instincts of fair play and justice…,” Naoroji wrote. “Self-government under British paramountcy or true British citizenship,” is how Naoroji described his alternative.

For many, this remains his greatest failing – he was simply unable to conceive of India without the sovereignty of the British. That being said, his critique itself opened the door for cold, impassioned analysis of the British Empire across the world, from Ireland to Africa, and, of course, India.