GI tag for Majuli masks of Assam: History, cultural significance of the centuries-old art form

The masks have been made in Assam's sattras, or monasteries, since the 16th century. Now, efforts are on to give them wider exposure and a commercial boost.

Adding to their growing national and international recognition, the traditional Majuli masks in Assam were given a Geographical Indication (GI) tag by the Centre on Monday (March 4). Majuli manuscript painting also got the GI label.

A GI tag is conferred upon products originating from a specific geographical region, signifying unique characteristics and qualities. Essentially, it serves as a trademark in the international market.

What are Majuli masks?

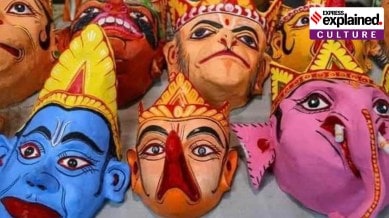

The handmade masks are traditionally used to depict characters in bhaonas, or theatrical performances with devotional messages under the neo-Vaishnavite tradition, introduced by the 15th-16th century reformer saint Srimanta Sankardeva. The masks can depict gods, goddesses, demons, animals and birds — Ravana, Garuda, Narasimha, Hanuman, Varaha Surpanakha all feature among the masks.

They can range in size from those covering just the face (mukh mukha), which take around five days to make, to those covering the whole head and body of the performer (cho mukha), which can take up to one-and-a-half months to make.

According to the application made for the patent, the masks are made of bamboo, clay, dung, cloth, cotton, wood and other materials available in the riverine surroundings of their makers.

Why is the art practised in monasteries?

Sattras are monastic institutions established by Srimanta Sankardev and his disciples as centres of religious, social and cultural reform. Today, they are also centres of traditional performing arts such as borgeet (songs), xattriya (dance) and bhaona (theatre), which are an integral part of the Sankardev tradition.

Majuli has 22 sattras, and the patent application states that the mask-making tradition is by and large concentrated in four of them — Samaguri Sattra, Natun Samaguri Sattra, Bihimpur Sattra and Alengi Narasimha Sattra.

The makers of the masks

Hemchandra Goswami is the sattradhikar or the administrative head of the Samaguri Sattra, and a well-known practitioner of the traditional mask-making art. According to him, masks had historically been made in all sattras, but the practice gradually died out in most over time.

“The arts of dance, song and musical instruments are closely tied to the sattras and the one who began this was Assam’s guru Srimanta Sankardev. In the 16th century, he established this art of masks through a play called Chinha Jatra. The word means explaining through images. At that time, to attract ordinary people to Krishna bhakti, he had presented the play in his birthplace Batadrava. There, he presented two masks, which were worn to express what a person’s face could not. One was the four-headed Brahma and the other was Garuda,” Goswami said.

He said that the Samaguri Sattra had been practising mask-making since its establishment in 1663.

Making the mask contemporary

Goswami said that while the masks were traditionally made only for the purpose of bhaonas, over the past couple of decades, the Samaguri sattra has been trying to promote mask-making as an art form in its own right. “For that, mask-making had to be made economically viable for artists. So we tried to increase the mask’s uses beyond its traditional one,” he said.

Among these have been the introduction of gifting small masks along with the traditional gamosas while felicitating guests at events, promoting the sale of masks to tourists at Majuli, and increasing their display at exhibitions and galleries— the masks have even found a place in the British Museum now.

Bismita Dutta, CEO of Kristir Kothia, the NGO which submitted the GI tag application, said the long-term aim was to further modernise the uses of the mask while preserving the tradition of the art.

“To preserve and popularise the art, we have held many workshops for new artists over the years with Hemchandra Goswami as our resource person. We want to make the sale of these masks a viable option for artists and the GI tag was one way to promote that. Gradually we also want to modernise them in a way to appeal to younger people, with more contemporary images. For example, a lot of people wear masks in Durga Puja festivities. So can we popularise these masks there?” she said.

What is Majuli manuscript painting, which also received the GI tag?

It is a form of painting — also originating in the 16th century — done on sanchi pat, or manuscripts made of the bark of the sanchi or agar tree, using homemade ink.

The earliest example of an illustrated manuscript is said to be a rendering of the Adya Dasama of the Bhagwat Purana in Assamese by Srimanta Sankardev. This art was patronised by the Ahom kings. It continues to be practised in every sattra in Majuli.