Aishwarya Khosla is a journalist currently serving as Deputy Copy Editor at The Indian Express. Her writings examine the interplay of culture, identity, and politics. She began her career at the Hindustan Times, where she covered books, theatre, culture, and the Punjabi diaspora. Her editorial expertise spans the Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Punjab and Online desks. She was the recipient of the The Nehru Fellowship in Politics and Elections, where she studied political campaigns, policy research, political strategy and communications for a year. She pens The Indian Express newsletter, Meanwhile, Back Home. Write to her at aishwaryakhosla.ak@gmail.com or aishwarya.khosla@indianexpress.com. You can follow her on Instagram: @ink_and_ideology, and X: @KhoslaAishwarya. ... Read More

The glove’s off—and on: Inside Margaret Atwood’s awaited memoir Book of Lives

Margaret Atwood Book of Lives: Margaret Atwood, forever the accidental prophet, writes her own origin story. She is wry, humorous, and still very much vertical, thank you!

Margaret Atwood Book of Lives: Margaret Atwood has always understood the art of doubling. She is the watcher and the subject. The voice of warning and the voice of doubt. She is the writer who observes, and the woman who lives. The prophet who sees it coming, and the skeptic who questions everything.

In Book of Lives, her first full-length memoir at 85, she lets the multitudes within her to speak to each other, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in amused dispute. “Every writer (has a)… body double (that) appears as soon as you start writing,” The Handmaid’s Tale author informs us, right at the start of her book. The book is then a conversation between the writer who lives, and the one who writes.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

The many Peggys

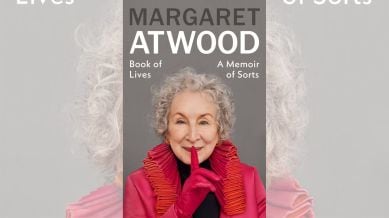

The cover – Atwood, finger to lips, fuchsia satin glove gleaming – captures the spirit perfectly. It is at once an invitation to share in the secret, a warning to hush at last with the conjecture, and a prophecy that the reader will lose themselves in her world.

“Publication day is almost upon us,” she wrote recently in her newsletter. “And I’m not exactly packed. But at least I have the fuchsia satin gloves.” The striking gloves, she explained, were a gift from her British editor, Becky Hardie, “brought from London,” and they have since become her cheeky companion. The gloves are symbolic, after all what is a a memoir, if not a slight of hand. It is the art of showing and hiding, a performance of revelation. The glove distracts even as it gestures. Atwood, ever the conjurer, knows that confession and concealment are twin acts, and that the shimmer is often found in what is withheld.

The British publicity team went a step further, producing a lapel pin and a set of postcards labelled See No Evil, Speak No Evil, Hear No Evil. “I enacted them during the last phase of a photo shoot,” Atwood writes, “during which I had been suitably black-clad and solemn, until this moment.” The image chosen for the cover was Speak No Evil. “Oh oh,” she quips. “False advertising.”

In Book of Lives, Atwood rewinds to the beginning. A childhood spent in the wilds of northern Quebec, where her father, an entomologist, studied forest insects and her mother, a dietician with a tomboy’s practicality, kept the family alive off the grid. There was no electricity, no running water — “sometimes not even a road.”

Days were spent canoeing, fishing, and reading whatever had been hauled north in the trunks. “It sounds forlorn,” she writes of her eighth birthday, “It was forlorn. It gets more forlorn.” Yet she also describes that isolation as formative, even ecstatic: “The forest was the great teacher. It taught you to look.”

It was there that the girl called Peggy Nature a nickname earned at summer camp, began to understand how observation and survival intertwine. Insects, trees, and weather systems became metaphors. Nature was not a retreat from human life, but a mirror of it.

Becoming ‘M E. Atwood’

Atwood’s adolescence introduced her to the politics of girlhood. She encountered “the unpredictable, oblique, underhanded, and Byzantine nature of the power politics practised by nine- and ten-year-old girls,” she recalls. The bullying that followed left its mark, and, years later, became the seed of her novel Cat’s Eye. From that early exposure to cruelty came her abiding fascination with how social, political, and domestic systems enforce submission.

By 14, she was already publishing poems under the name “M E Atwood.” “So I wouldn’t be tagged as a girl,” she writes. The act was both disguise and an act of defiance. It would be the first in a lifelong series of masks. At the University of Toronto, and later at Harvard’s Radcliffe College, she encountered scholars such as Northrop Frye and Marshall McLuhan, whose theories of myth and media would feed her own. While researching the Salem witch trials, she realised how fear and power entwine, a preoccupation that decades later would crystallize in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Atwood has never claimed to be a prophet or saint, but sainthood has been bestowed on her thanks to The Handmaid’s Tale.

“Increasingly,” she observes, “I was viewed as a combination of figurehead, prophet, and saint — expected to do the Right Thing for women in all circumstances, with many different Right Things projected onto me from readers and viewers.”

In Book of Lives, she recalls an incident that captures the burden of being cast as a moral oracle. During the run of The Handmaid’s Tale television series, she wore a brooch given to her by the show’s team, an innocuous accessory, or so she thought. Soon, letters began to arrive. “It was from a member of what might roughly be called a Pagan goddess group,” she writes, “asking how I could have done such a terrible thing to them all.” The brooch, it turned out, bore a figure of “a naked woman standing on a half-moon with several stars around her” — Astra, the Sacred Star Goddess. “The group was very annoyed.”

A follow-up letter came from “Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, a friend of the first letter-writing group, a wizard. He informed her that the moon-woman image was copyrighted, and enclosed the paperwork. Ultimately, she did her best to redress the grievances of the wronged parties. The anecdote is quite the delight to read.

Love & loss

Another great influence has been her long partnership with fellow novelist Graeme Gibson, who died in 2019 after a slow decline into dementia. Book of Lives recounts their 50-year life together . We learn of their their courtship (she was married, he was not quite single), their move to a farm near Alliston, Ontario, their adventures in beekeeping and birdwatching, and their shared devotion to work.

Marriage, as it turns out, was the one story Atwood did not get to write. “As for marriage, never assume anything,” she begins.

“Graeme has now announced that he doesn’t want to get married because he’s already known three Mrs. Gibsons — his mother, his stepmother, and his ex-wife — and he doesn’t want to create another one.” She considers it, in her inimitable way, both “a compliment of sorts” and “hilarious.”

But the situation left her trapped between feminist myth and personal circumstance: “Here I am,” she writes, “being praised by feminists as a role model for my courage in having a baby ‘out of wedlock’ and also for holding out against the wicked patriarchal attempt to impose a married name on me against my will, whereas none of this was my idea at all.” Two of the Mrs. Gibsons were still alive, she notes, so she bit her tongue. “I hate being given five gold stars for my brave unmarried state — it’s like being handed a prize for a contest you haven’t entered — but there’s nothing I can do about it without adding more knots to an already knotty equation.” The whole episode ends, inevitably, with the dry aftertaste of resentment: “This irritates me, and I smoulder with resentment.”

Gibson’s death shadows the memoir’s later pages, but never overtakes them. Atwood admits that she threw herself into work to avoid the void. “Ask yourself, Dear Reader,” she writes. “The busy schedule or the empty chair? I chose the busy schedule. The empty chair would be there when I got home.” It’s one of those crystalline Atwood sentences.

The brooder and the trickster

Throughout Book of Lives, Atwood toys with her public image, the stern oracle with Medusa curls, and dismantles it with glee. “My Medusa eyes go with my Medusa hair, which used to be referenced in book reviews, back when invective was more uninhibited and body-shaming was the norm, especially when men were reviewing women,” she writes. She jokes that one glance from her “baleful eyes” could “freeze men’s gonads to stone.”

She also writes about how her fascination with Tarot cards grew thanks to them being an “essential for the study of TS Eliot.” Her whimsical fascination with tarot cards, and horoscopes is an extension of her writer’s logic. “We Scorpios make implacable enemies,” she writes. The wit is barbed, but tell us that Atwood treats superstition as metaphor, a map of human desire and dread.

She is extraordinarily self-aware. “I am a sulker and brooder. Quick anger flare-ups and fast diminuendos are no doubt preferable, but I am what I am,” she writes.

Still vertical

Atwood ends not in reflection but motion. She is on tour again — Toronto, New York, London, Berlin — armed with medication, handlers, and humor. “I have a suitcase full of medications and several anxious Minders,” she writes in her newsletter. “But all is well. Hey! I’m still vertical!” The line lands like a toast.

Book of Lives is not a swan song. It’s a reclamation of memory, of voice, of the right to narrate one’s own myth. In its pages, Atwood gathers her many incarnations — Peggy the tomboy, Margaret the scholar, M.E. the masked poet, Aunt Lydia the prophet, and lets them quarrel, forgive, and coexist.

After a lifetime spent warning the world of its own follies, Atwood turns the gaze inward. The result is radiant, mordant, and unmistakably hers.

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood

Publisher: Doubleday

Pages: 608

Price: ₹1,514 (Kindle)