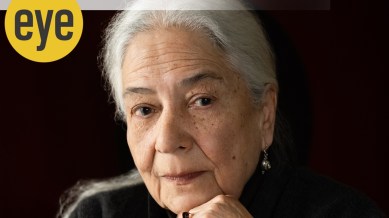

Anita Desai on new novella Rosarita, her changing relationship with India and why families never cease to surprise

In the sparsely-written work, Desai explores the unknown layers to individual lives that get subsumed in the quiet violence of the everyday

Who are we when we are unencumbered by familial relationships? Does the mundanity of the everyday leach one of the possibilities of what could have been if only one had been brave enough, if circumstances had been different enough, the world more conducive to all that burns within? It’s a landscape that Anita Desai, 87, has returned to again and again. But in Rosarita, her novella after more than a decade, Desai looks back, through the eyes of a young woman Bonita, at the life of a mother the Indian language student had always considered to be prosaic. In a park in San Miguel, Bonita is accosted by an older woman who sees in her the image of her artist friend, Rosarita. Bonita protests — her mother, Sarita, had never been to Mexico; she certainly wasn’t an artist. But, in the face of the older woman’s unwavering insistence, her conviction begins to waver. Could her mother have had more to her than she’d ever known? Did she never see her as a person of her own, only ever as a parent? In her sparsely-written novella, Desai explores erasures of a different sort and the unknown layers to individual lives that get subsumed in the quiet violence of the everyday. In this email interview, Desai speaks of why she’s tempted by brevity in art, the secrets that families hold and her changing relationship with India. Edited excerpts:

In Sonar Tori, Rabindranath Tagore wrote of the appeal of short stories — microcosms that leave a lasting impression even when the narrative gets over. Rosarita reminded me of it. What does this brevity that has characterised your work mean to you?

I have written larger, fuller books that have more fully explored my characters, their histories and their worlds. But I have always felt the need for space. Those are the books that linger in the mind, as Tagore said, because they require the reader to enter into them and fill them with their imagination. These are the books that give them the invitation to do so — by not answering every question but allowing one to find one’s own.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Was there anything in particular that led you to Bonita’s story?

The book was made up, as all are, of a collage of memories, impressions and experiences, then trying to find out what links them. Writing is rather like working out a jigsaw puzzle: you pick up all these random pieces but they remain scattered and chaotic until you find a pattern to which they belong. The book is that pattern.

The second person is rather an unusual narrative mode. Tell us how you settled on it to tell Bonita and her mother’s story?

It was an experiment. I wanted to try out and it seemed to fit the novella form because it helped to plunge the reader directly into the narrative without any preamble. Also, it gave it an immediacy it might otherwise have lacked being set as it is in disparate and remote locations that might not have seemed obviously to cohere.

The family lies at the core of much of our life experience but we also know so little about the people we think we know the best. What is it about families that intrigues you the most?

A family occupies a limited, enclosed space. One would think everyone knows everything there is to know about each other only to learn with time how little one really knows, how much one tends to miss or misunderstand and also forget. So what is most familiar can also present the deepest mystery. One certainly draws upon what one has observed and experienced for one’s writing. But it is also a creative exercise — one is not encumbered by or reliant solely on facts. Yes, inspiration lies all around one but writing requires one to imagine them.

What has writing meant to you?

Writing has been a part of me as much as breathing, and as essential. That has not changed over the years. It has formed my way of life and through it. I have always tried to set aside at least a brief time of the day to sit down alone and put pen to paper if only to write a letter, a note in a diary, nothing at all, but to maintain a connection with words, with language.

Age inevitably affects one’s writing as it does all else. I write less and what I write is of necessity pared down. I have neither the time nor the energy or the stamina for more.

What does a sense of place mean to a person like you who has inhabited so many worlds? Is there any one place where you feel most at home?

A sense of, an awareness of the places I visit or inhabit has always been a strong element of my being. It has made travel a mostly wonderful, inspiring experience. But belonging? That’s another thing. I think that when one is seen as a stranger, one remains an outsider. Perhaps that is what makes a writer one too — an observer, not a participant. I have to carve out a space for myself wherever I am and call it home at least temporarily.

How does that shape your relationship with India now? How do you look upon its many changes?

I used to think of myself as a turtle who carried India on my back as my home but that is no longer so. I still have family and friends in India and therefore continue to visit — less frequently now that it has become physically difficult and also because it has ceased to be the country I once knew in another time and age. I did not participate in the making of what India is now, so in a way it no longer belongs to me. That makes it difficult to return or remain.