How China’s Brahmaputra dam raises serious concerns

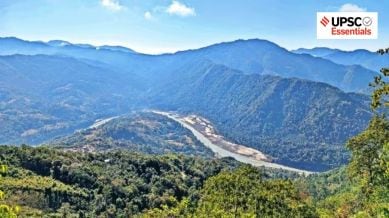

The location of China’s proposed dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River poses a risk of disrupting the river’s natural flow, raising concerns in India over its impact on the region’s biodiversity and agricultural productivity.

— Abhinav Rai

(The Indian Express has launched a new series of articles for UPSC aspirants written by seasoned writers and scholars on issues and concepts spanning History, Polity, International Relations, Art, Culture and Heritage, Environment, Geography, Science and Technology, and so on. Read and reflect with subject experts and boost your chance of cracking the much-coveted UPSC CSE. In the following article, Abhinav Rai, a Doctoral researcher working on the impact of climate change on glacier dynamics in the Himalayan Region, examines China’s proposed dam on the Brahmaputra River.)

At present, the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River in China is the world’s largest dam with an installed capacity of 22.5 gigawatts. The location of Beijing’s planned dam near the “Great Bend” of the Yarlung Tsangpo (or Zangbo) river in Tibet is suitable for hydropower generation due to the deep slope, where the river drops 2,000 meters over a short distance of just 50 kilometers. On completion, the 60,000 MW project will have the capacity to produce three times the amount of electricity as the Three Gorges Dam.

The location of the proposed dam, where the Brahmaputra river makes a sharp U-turn to flow into Arunachal Pradesh and then to Bangladesh (where the river is known as Jamuna), poses a risk of disrupting the river’s natural flow. It could affect agricultural productivity (for crops like rice and jute) and biodiversity hotspots such as the Eastern Himalayas.

Let’s analyse the dam’s specifications, its geographical context, and possible environmental and geopolitical implications.

A river with many names

The Brahmaputra is a transboundary river with its basin spreading approximately 5,80,000 square kilometers across China (50.5%), India (33.3%), Bangladesh (8.1%) and Bhutan (7.8%). In India, it covers 1,94,413 square kilometers, which is about 5.9% of the country’s total geographical area. It encompasses areas of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Sikkim and West Bengal.

The river originates from Chemayungdung Glacier located in the east of the Mansarovar Lake in the Kailash ranges of Tibet. It flows eastward for nearly 1,200 kilometers in Tibet as the Yarlung Tsangpo River. At Namcha Barwa, the river takes a ‘U’ turn, known as the Great Bend, and enters India through Arunachal Pradesh (west of Sadiya town), where it is known as the Siang/Dihang River.

After flowing southwest, it is joined by the Dibang and Lohit rivers as left-bank tributaries and subsequently, it is known as the Brahmaputra River. Important right-bank tributaries of the Brahmaputra are Subansiri (antecedent), Kameng, Manas and Sankosh rivers. The river then flows into Bangladesh plains near Dhubri in Assam, from where it flows southwards. It is known as Jamuna in Bangladesh after Teesta joins it from the right bank. It merges with river Padma before draining into the Bay of Bengal.

Brahmaputra’s unique flow

The Brahmaputra River is unique in the sense that it flows in diametrically opposite directions like from west to east in Tibet and east to west in Assam. The gradient of the river provides a suitable geographic condition for hydroelectricity generation. The river experiences a drop of about 4,800 meters in its slope during its 1,700 kilometers course in Tibet before entering India. This steep mean slope of about 2.82 m/Km is reduced to 0.1m/Km when it enters Assam Valley.

Although China is emphasising the importance of this project in achieving its renewable energy goals, lower riparian states – India and Bangladesh – are susceptible to its impact on the river’s water flow, ecological stability, and regional geopolitics.

Moreover, meteorological conditions of the Brahmaputra River’s catchment are very different in Tibet and India. In its early course in Tibet, the river passes through very cold and dry regions carrying less water and silt. But in India, it is joined by several tributaries bringing huge volumes of silt and a large volume of water. Due to the deposition of this silt, the river channel becomes braided even forming riverine islands. Majuli (area of 352 square kilometers) is the world’s largest riverine island formed by the Brahmaputra River in Assam.

All its tributaries in India are rainfed and receive heavy precipitation during the southwest monsoon. This heavy precipitation causes frequent floods, channel shifting and bank erosion.

Impact on India’s hydropower projects

China’s plan to construct the dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River would add another layer of complexity to the river’s natural dynamics. Although China is emphasising the importance of this project in achieving its renewable energy goals, lower riparian states – India and Bangladesh – are susceptible to its impact on the river’s water flow, ecological stability, and regional geopolitics.

India also has many hydropower projects at different stages of their development. This includes Lower Subansiri (2,000 MW), Dibang (3,000 MW), Kameng (600 MW), and Ranganadi (405 MW) of Arunachal Pradesh, the Kopili (200 MW), Khandong (75 MW), Karbi Langpi (100 MW) of Assam, Teesta-V (510 MW) of West Bengal,Umiam-Umtru Power Complex (174 MW) of Meghalaya, etc. In the case of reduced water supplies, these projects will be adversely affected.

The planned dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River also raises concerns because the region is seismically very active and earthquake-prone. This is the region of the geological fault line where the Indian and Eurasian plates are colliding. Any large-scale physiographical disturbance could potentially cause a geological disaster. The Dam also threatens the Himalayan ecological balance and its biodiversity.

Need for enhanced transboundary cooperation

Besides, China now has the highest number of operational dams than the rest of the world combined. After utilising much of its internal rivers, now it is focusing on transboundary rivers. China has aimed to reach its peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. The proposed dam project is part of its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) and Long-Term Goals 2035. To achieve these ambitious targets, the Chinese government is focusing on renewable energy sources with a greater focus on hydropower.

However, this focus on transboundary rivers, particularly the Brahmaputra basin, raises serious concerns for downstream countries like India and Bangladesh. The Brahmaputra basin faces increasing pressure from the growing population, climate change, changing consumption patterns, and the pursuit of hydroelectricity to achieve energy requirements and meet green energy targets.

Despite existing MoUs and an Expert-Level Mechanism established in 2006, India and China do not have any formal water-sharing treaty to share hydrological data of trans-border Rivers. Therefore, transboundary cooperation, real-time hydrological data sharing and environmental impact assessment of such projects are needed to ensure ecological balance and sustainable flow of the river.

Post Read Questions

What are some of the environmental concerns associated with constructing a large dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River?

What are some potential consequences of altering the natural flow of the Brahmaputra River for downstream communities?

How might the dam project affect agricultural productivity and biodiversity in downstream regions?

How can the environmental and geopolitical risks associated with the dam be mitigated?

(Abhinav Rai is a Doctoral candidate at the Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi.)

Share your thoughts and ideas on UPSC Special articles with ashiya.parveen@indianexpress.com.

Subscribe to our UPSC newsletter and stay updated with the news cues from the past week.

Stay updated with the latest UPSC articles by joining our Telegram channel – IndianExpress UPSC Hub, and follow us on Instagram and X.