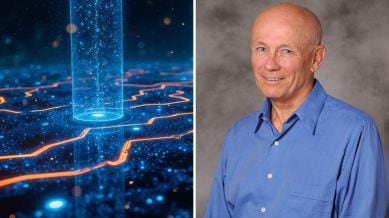

AI has tremendous potential for ‘creative destruction,’ says Canadian Nobel winner Peter Howitt

Nobel winner Peter Howitt says AI is the latest and most powerful example of ‘creative destruction'. It is boosting the economy while disrupting jobs.

Canadian Nobel winner Peter Howitt believes that artificial intelligence (AI) symbolises the most dramatic shift in our times. “It has tremendous potential to benefit mankind but also tremendous potential to destroy the value of a lot of people’s human capital,” he said.

At the centre of Howitt’s work is a paradox. Every technological leap, from the steam engine to artificial intelligence, propels humanity forward while simultaneously displacing those tied to outdated systems. “Every new technology that has a major impact on the economy provides great benefits for most people,” he said in an interview with CBS News. “But there’s always someone who’s hurt by it, someone that relies upon the technologies that are replaced.”

According to Howitt, this tension creates an unavoidable conflict. “Those people whose technologies are going to be replaced are going to try various ways to block the new technology to prevent everybody from getting these benefits,” he noted. Howitt emphasised the moral dimension of such transitions, suggesting that those displaced by innovation “should share in the benefits like everyone else.”

He believes that artificial intelligence represents the most dramatic current example of this process. “Of course, nowadays the big technology that we’re all worried about is artificial intelligence,” he said.

The rapid progress of AI, he warned, risks rendering human expertise obsolete. “Instead of hiring you for your knowledge, you can let a computer do the work,” Howitt said. According to him, this dynamic fits the classic model of ‘creative destruction’ – which is essentially a technological revolution that generates prosperity while eroding established professions.

However, Howitt remains cautiously optimistic. For long, his work has shown how societies capable of managing these disruptions through education, social support, and open markets can emerge stronger in the process. He implied that the challenge does not lie in stopping innovation but in making sure that its benefits are reaped by all.

Apart from technology, Howitt’s model also underscores why global trade is pivotal for sustaining innovation. The economist warned that restricting trade can likely shrink markets and stifle incentives to innovate. “Growth depends upon innovations,” he said.

“Innovations will only take place if people find it profitable to do so. The smaller that market is, the less profit there is – and therefore the less incentive there is to innovate.”

While reflecting on a lifetime of research which is now recognised by the world’s highest economic honour, Howitt continues to remain humble. His valuable insights based on decades of economic modelling may have been forged long before the rise of ChatGPT or AI-powered factories. However, his message that progress and disruption are inseparable feels timeless.