Women artists pay tribute to Ajeet Cour’s life and writings

The exhibition, inspired by her autobiography, is a collective visual narrative of memory and resilience

One of the leading names in Punjabi literature, the details of author Ajeet Cour’s turbulent life became most intimately known through her 1983 autobiography Khanabadosh, which was later translated from Punjabi to English in 2018 as Weaving Water. Seven years later, her words have now attained a visual language through the works of 15 women artists who have responded to the various chapters from her life, beginning with her formative years in Lahore, where she was born in 1934, and had a home she was forced to flee during Partition, becoming a witness to the violence and displacement of the riots that shaped her future in profound ways.

Taking place at the India International Centre, the exhibition ‘Weaving Water: Feminine Countercultures in Paint and Print’ juxtaposes Cour’s words from her autobiography with those of the participating artists, sharing parallels between their artwork in the exhibition and her writing. The dialogue also leads to a reflection on persistent gender inequality and explores feminine countercultures through art and expression.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

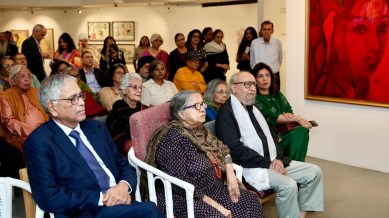

At 90, as Cour mingled with the audience at the opening on October 30, the evening became a tapestry of memories, not all joyful, but each revealing a life lived to the fullest. “I feel exalted that this book, written nearly 50 years ago, has inspired so many significant artists to create works in response to it. Their powerful art is proof that this book has been able to convey the message of life and death, pain and anguish and a life lived in struggle, with the courage to fight it,” stated the Padma Shri-winning Cour, adding, “I have been fighting all alone but now my daughter Arpana (Caur, artist) shares my struggle and is a great support.”

Known for her politically charged and socio-realistic writings, if her 1974 work Gauri is a tale of a woman who challenged patriarchal norms, The Other Woman (2014) comprises short stories with defiant female protagonists who challenge stereotypes. Her two-part memoir, Khanabadosh (1983) and Koora Kabara (1997), paints a picture of her life, demonstrating her indomitable spirit.

At the very onset of the exhibition, artist Nitasha Jaini responds to Cour’s self-description as the “wayward, unbridled one” through an installation where she depicts, through a wall installation, the author’s restlessness upon being confined inside the four walls of domesticity. In another floor work, titled Khanabadosh II, a trunk appears as a symbol of travel and repository of memories with several objects that include archival photographs of Cour, prayer beads and a fountain pen.

While Durga Kainthola also paints over archival photographs to honour Cour’s unyielding resilience, curator Jyoti A Kathpalia places Vasundha Thozhur’s Portrait of Shah Jehan in conversation with the trauma of the Partition as experienced by Cour. Kathpalia writes, “Thozhur, like Cour, refuses erasures, insisting on the closeness of art to life which makes it a medium for holding the unbearable and makes remembrance itself an act of resistance.”

If Jayasri Burman’s acrylic and charcoal on canvas Jeevan Nadi celebrates the free-thinking feminine self, Bula Bhattacharya revisits Cour’s abusive marriage and struggles as a single mother through her set of hand-painted silk screen prints titled Role Playing, which reflect on the layered nuances of the nonagenarian’s life through image and text. In her crocheted copper-enamelled aluminium wire installation, Shivani Aggarwal weaves the complexities of life and reflects on the irony of confining expectations and social conditioning that stifles individual dreams and aspirations.

A tribute also comes from Caur, whose Earth and Sky depicts a woman reaching out for her own sky to represent how everyone is seeking a fairer share. In the canvas River of Blood, she has Sohni from the tragic folktale as the fearless lover who dared to plunge into the turbulent Chenab to reach her beloved Mahiwal. “These works reflect my mother’s courage and the enduring spirit of women who refuse to surrender to circumstances,” states Caur.