Artist Vasundhara Tewari Broota’s new solo traces the realistic female form

The exhibition, on display at Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery, carry the quiet insistence that women’s lives, like nature itself, hold strength and complexity

When visitors step into Woman Song | Looking Back at Vadehra Gallery in Delhi, they are not just greeted by paintings but by fragments of memory — a grandmother who is ready to pose, a sister captured midrest, or flowers reimagined as emblems of feminine force. On till October 11, the exhibition brings together 35 works spanning four decades of Delhi-based artist Vasundhara Tewari Broota’s practice, tracing her exploration of the female form as an embodiment of strength, intimacy and resistance.

Vasundhara started her journey by making forms and portraits of those closest to her – her grandmother, her sister who when asked to pose for portraits would just lie down lazily. The female body, not stylised or adorned, became her natural subject. “I was drawn to making the figures not because I wanted to depict ordinary life, but because the form became a channel for my expression,” she says. This instinctive pull that she felt towards portraying bodies set the foundation for a career that has consistently pushed against decorative portrayals of women.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

In her work Seva (1982), Broota turned her gaze towards her grandmother’s arthritic body — folds of flesh and softened contours — and placed it centre stage. What many would see as signs of age, she reframed it as beauty. The inclusion of her grandmother’s helper’s hands in the same frame recalls the layered presence of women in domestic life. With this she not only celebrates, but challenges invisibility and honours the strength found in the most ordinary forms.

Experimentation with materials and methods further shapes her practice. Beginning with oil on canvas, she was soon drawn to the richness of black ink used in printmaking, shifting towards paper and stencils to create depth and variation. “It was all from the desire to express,” she explains, recalling how her studio became a ‘safe space’ where work unfolded without the pressure of display. This freedom led to works like Golden Bird, a textured piece which is also embedded with coins and matchsticks, referencing India’s history of being the golden-bird and its subsequent plunder.

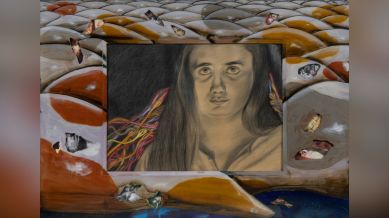

The personal threads are especially visible in her work Looking Back (2001) where Vasundhara overlays a self-portrait with acrylic panels, leaving little windows to frame family photographs. “It was like an album you didn’t have to pick up and open – it was always present,” she says. The images – of her parents, a picnic, nieces and nephews — were moments captured and unposed, elevating the everyday into a permanent record of presence.

Nature appears as another recurring force. In Exhale (2022), which was created during the pandemic, there are roots and branches collaged with newspaper cuttings. “Nature is a force in itself. You can’t suppress it. We think we master it, but floods and droughts remind us otherwise,” she notes. The stained newsprint – with its headlines from the COVID-19 crisis – makes the branches a site of collective memory. Yet the work also captures a striking dichotomy of life in the current times: even as the world burns, life continues in its mundane rhythms of eating, sleeping and exercising.

Flowers too, are recurring in Broota’s imagery but not as decorative motifs. “For me, the flower is a feminine force,” she insists. Her flowers take centre stage as strong, sensitive presences – much like the women she paints.

Across her four-decade long career, she has consistently asked viewers to look beyond the surface. Whether it is her grandmother’s body, a self-portrait that holds others or a branch collaged with newspaper, her works carry the quiet insistence that women’s lives, like nature itself, hold strength and complexity.