📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

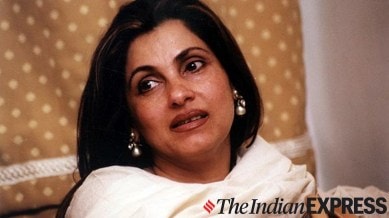

‘I’m nervous the entire time I’m working’: Dimple Kapadia on her self-critical nature and nervous energy at work

"I know nobody is watching me do my thing at home, but I’m always watching myself," Dimple Kapadia said

Dimple Kapadia has been an icon in Indian cinema for decades, yet behind her celebrated performances lies a surprising truth: a persistent, self-critical nature. In a recent interview with Vogue India, the actor revealed, “I’m nervous the entire time I’m working… Even when I’m making art, my jaw begins to hurt at the end of it, and I realise it’s from clenching it all day. I know nobody is watching me do my thing at home, but I’m always watching myself.”

Kapadia’s unique form of self-monitoring may have its downsides, but it also serves as a driving force that pushes her to give her best at her job. “That constant tightness in my stomach when I’m on set? It’s inherent and probably what makes me tick. The day I lose it, I lose something important.” This offers an insight into how self-awareness, for better or worse, plays a role in professional dedication and personal growth. But what makes self-monitoring constructive, and when does it become destructive?

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

How can individuals identify if self-criticism is motivating or veering into self-sabotage?

Gurleen Baruah, organisational psychologist and executive coach at That Culture Thing, says, “Self-criticism, that inner voice in our heads, is more common than we often realise. It’s something many people experience daily, and it can serve two distinct roles. When self-criticism is constructive, pushing for growth, learning new skills, or striving for improvement through consistency and discipline, it can motivate. This critique is usually specific, solution-oriented, and focused on progress.”

However, she adds, when self-criticism becomes self-loathing, it shifts from being helpful to harmful. This is when it turns into thoughts like ‘I’m not good enough,’ ‘I’ll never succeed,’ or punishing oneself for perceived failures. Instead of encouraging growth, it erodes self-worth and confidence, leading to feelings of shame or frustration.

“One way to distinguish between the two is by paying attention to the tone and outcome of the inner voice. Constructive criticism feels like a nudge to do better while self-sabotaging criticism feels more like an attack, filled with harsh judgments and impossible standards,” Baruah says.

Practical strategies that can help transform nervous energy or tension into a positive force for productivity or growth

Baruah states, “One effective way to transform nervous energy or tension into a positive force is by first taking a moment to sit and observe what you’re feeling. Acknowledge the emotions — whether it’s anxiety, frustration, or self-doubt — without judgement.”

Once you recognise them, she says, you can approach that inner voice of tension or nervousness with compassion.

A practical technique rooted in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the ABC model:

Activating event: A negative situation occurs (e.g., a tight deadline at work).

Beliefs: The thoughts or explanations you create for why this happened (e.g., “I’m not prepared, and I always mess up under pressure”).

Consequences: The feelings and behaviours that result from these beliefs (e.g., procrastination or anxiety).

To break this cycle, Baruah suggests challenging your beliefs. In this example, rather than focusing on ‘I’m not prepared,’ reframe it to ‘I can tackle this step by step, starting with what’s in front of me.’

Another powerful strategy is simply getting started, she elaborates. “Just begin—without overthinking the outcome or imagining what could go wrong. As soon as you take those first steps, momentum will build, and the nervous energy can transform into focus and productivity.”

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram