📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram

From seated Betha to martial Raas: A look at the diversity of Garba across Gujarati communities

“Garba’s diversity is the result of Gujarat’s long history as a crossroads of trade, migration, and regional identities,” says an expert

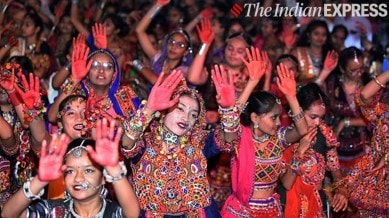

What we know today as Garba, the vibrant, rhythmic dance that fills Gujarat’s nights during Navratri, has roots that stretch back thousands of years, weaving through mythology, literature, and the very fabric of Indian culture.

According to Gujarati poet and writer Himanshuray Raval, the story of this beloved dance form is far more complex and fascinating than most people realise. Historically, Garba reflected the rich diversity of Gujarati communities. “Garba can be classified into 36 broad styles of performance. This is so because all big communities have their own subculture, their own dialects, etc., and their own saints,” Raval explains in a conversation with indianexpress.com.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

How Garba evolved into such a diverse cultural expression across communities in Gujarat

Amrut Patel, principal at Visha Nagar Panchayat Arts and Commerce College, mentions, “Garba has existed since very ancient times, tracing back to the Harappan civilisation and even to the Rig Veda. References to the Mother Goddess, or Usha Devi, the goddess of fertility and agriculture, appear in several Rig Vedic hymns. This worship, which began as formless devotion, gradually transformed into worship of a tangible deity.”

Saru Subba, historian and founder at Carol School Guwahati, tells indianexpress.com, “Garba’s diversity is the result of Gujarat’s long history as a crossroads of trade, migration, and regional identities. What began as a devotional dance around the earthen lamp or garbo to honour the feminine divine gradually absorbed the customs of local castes, occupational groups, and rural traditions.”

He adds that communities such as the Mers, Kolis, Kanbis, Adivasis, and Vadnagra Nagars “shaped the music, steps, and storytelling to reflect their own livelihoods and social rhythms.” Over centuries, Garba evolved from a single folk form into a shared festive framework where each group could imprint its own sense of pride and memory.

The Mers community

According to Subba, variations like the Mer Raas or the Maniyaro Lathi Daav Raas “reveal how dance once served as both entertainment and a coded display of strength.” The Mers were historically linked to warrior lineages and coastal defence, he says, and their circular formations and stick play echo martial drills and collective solidarity.

These performances connect dance with social identity and martial traditions, notes Patel, reflecting the community’s valor, hierarchy, and everyday life. Mannyaro songs are sung primarily during Raas, blending festivity with elements of martial training, ritual, and communal celebration.

The Gof Gunthan Solanga Raas, performed by Koli and Kanbi men

The Gof Gunthan Solanga Raas is remarkable for the way dancers weave ropes into intricate braids and then seamlessly unwind them.

“The crisscrossing patterns are often interpreted as metaphors for cosmic order and human interdependence, with the ropes binding individuals into a larger cosmic weave before restoring harmony. The traditional set of sixteen dancers reflects the agrarian calendar and lunar cycles, with sixteen seen as an auspicious number representing fullness and seasonal completeness,” explains Subba.

The Adivasi variations

Adivasi forms, such as the Divasa Garba, retain a closer relationship to nature and ancestral rituals than the urban Navratri styles. Subba states that their drumming patterns “mimic forest sounds and their movements often narrate agricultural cycles or spirit-invoking ceremonies.”

He adds that rather than focusing on the goddess in a strictly temple sense, these dances honour earth deities, seasonal change, and community cohesion, reflecting a cosmology where humans, animals, and landscape share a single sacred continuum.

The Vadnagra Nagar community

The Betha Garba is performed seated, Patel reveals, mostly by women in the Vadnagra Nagar community. “Women in this community were considered delicate and did not participate in vigorous physical activity. Sitting Garba allowed them to engage in devotional performance while respecting social and bodily limitations.”

Competitions for seated Garba are still held annually in Gandhinagar, he remarks. “Unlike the energetic Raas or Garba of the Mer and Vagher communities, Betha Garba focuses on devotional expression, praise of the Mother Goddess, and community cohesion rather than physical vigour.”

Are community-specific Garba forms at risk of being overshadowed?

Suba says that the statewide popularity of Navratri has brought Garba to global stages, but it also risks flattening its many local dialects of movement and music. He mentions, “Traditional forms survive where community elders, folk academies, and cultural trusts organise workshops, document oral histories, and teach younger dancers within village settings.”

Some municipalities and universities now sponsor heritage festivals and competitions specifically for these lesser-known styles. The challenge is to keep these initiatives community-led so that the dances remain living traditions rather than museum pieces, concludes the expert.

📣 For more lifestyle news, click here to join our WhatsApp Channel and also follow us on Instagram