Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

What ails the farm sector part-2: Politics brings bitter turn for sugar barons, drip irrigation for cane still to catch up

The state produces 36 per cent of the country’s sugar stock, making it the largest producer of the sweetener in the country. India is the second largest producer of sugar in the world and is the largest consumer as well.

Well over two years since the Congress and Nationalist Congress Party lost power in Maharashtra, the state’s sugar barons are still coming to terms with the loss of political patronage for the sugar sector. Known for their political significance during the previous regime, while the major sugar millers with deep-rooted networks in the cooperatives and farms now find themselves isolated from the power centres, they say the sector — with a Rs 50,000 crore annual turnover in the state — is suffering on account of political neglect.

Sugar has been a historically important commodity in Maharashtra, given its socio-political relevance. The state produces 36 per cent of the country’s sugar stock, making it the largest producer of the sweetener in the country. India is the second largest producer of sugar in the world and is the largest consumer as well.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

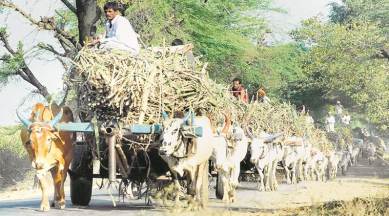

The sugar sector in Maharashtra, besides its huge annual turnovers, is also a major employment generator in rural areas. Naturally, the position of sugar in the state’s economics cannot be overstated – any distortion in production gets planners in a tizzy.

On paper, the state has 175 cooperative and 72 private erected mills, but the number of mills that actually participate in a season have been fewer. In fact, sugar production in 2016-17 fell considerably, with back to back droughts leading production to fall to only 42 lakh tonnes (lt) of sugar as compared to the 84.1 lakh tonnes in the previous season. For the coming season, the state is projected to produce around 70 lt of sugar, still much lower than the 100 lt mark the state reached a few seasons back.

Historically, the sugar sector in Maharashtra has always been close to power. Sugar barons – barring a few – have been inclined towards the Congress and Nationalist Congress Party, with the latter holding sway over the sugar-rich western Maharashtra region through a close relationship with the rural elite, this political patronage bringing growth to the region but also pitfalls.

In drought-prone parts of western Maharashtra itself where there is plenty of cane cultivation, such as in Solapur, and in large pockets of Marathwada too, sugar cultivation is at the centre of a controversy for the sheer quantum of water needed for these stretches of farmland.

What ails the farm sector part-1: Maharashtra farmers angry despite bumper pulse harvest, prices crash on oversupply | Click here to read

The district of Solapur is a classic case of the growth of sugar sector in an otherwise drought-prone area. Annually, the district receives barely 550-650 mm of rain. Yet, the district has 38 installed mills – the most for any district in the state. In its report on Pricing Policy of Sugarcane: 2013-14, the Commission for Agriculture Costs and Pricing (CACP), Ministry of Agriculture, draws some harsh truth about the state’s cane group. It says for production of 1 kg of sugar, Maharashtra requires 2,068 litres of water whereas Uttar Pradesh requires about 1,044 litres, making the water stress caused by the crop in drought-prone regions a serious problem.

Adding to the imbalance is that while barely 20 per cent of Maharashtra’s farm lands are irrigated, almost 80 per cent of existing irrigation facilities in the state are concentrated in cane-growing areas. This anomaly, for a crop that occupies just about 10 lakh hectares of land, means that one single crop has cornered the major portion of irrigation facilities. Water experts including India’s ‘waterman’ Rajendra Singh, as well as multiple reports of the CACP, have discussed the option of mandating drip irrigation for cane.

Amid the intensifying debate on the inequitable water distribution in favour of sugar, the state has recently made it compulsory for cane growers to install drip irrigation systems. Despite the efforts, until now, only 30 per cent of Maharashtra’s cane-growing area has come under drip irrigation, with growers complaining of difficulties in raising finance for the project. Subsidies are hard to come by, say farmers.

Environmentalist Vishambhar Choudhari points to the water-intensive nature of cane and says a compulsory drip system is a good move. “The cane crop doesn’t add much in terms of soil nutrients but the fixed returns lure farmers to it,” he says. The only way farmers can be weaned away from cane, he says, is to ensure equal and better returns for other crops such as pulses.

Simultaneously, the changes in the political landscape have meant sugar barons are no longer assured of a sympathetic ear in the government. For millers, for example, easy access to finance from government institutions has disappeared. Minister of Cooperation Subhash Deshmukh, whose family runs three private mills under the Lokmangal banner, has repeatedly talked about the need for millers to spruce up their act. To cite one example, millers have been asking for the last two years for a restructuring of the soft loan extended to them to pay growers from the 2013-14 season, but the government has not accepted their demand. Millers are at present repaying the Rs 3,000 crore extended to them by the state and central government.

Shivajirao Nagawade Patil, president of the Maharashtra State Cooperative Sugar Factories Federation, says the market for the state’s sugar has shrunk over the last two years. “Earlier we used to send sugar to Kolkata but the transport costs have made that uneconomical,” he says. Uttar Pradesh, Nagawade Patil says, has captive markets in Rajasthan, Delhi and other states that continue to elude Maharashtra’s millers. “We have been asking for restructuring of loans but the government is yet to respond,” he says.

Congress MLA and director of Latur-based Manjara Cooperative Sugar Mill Amit Deshmukh cites the state government’s refusal to execute a power purchase agreement (PPA) with the mills as another example of official apathy towards the sector. The state government has consistently refused to accept the Rs 6 per unit rate quoted by the millers to sell excess power generated through cogeneration plants. A special committee has been formed to look into the matter now.

For growers, cane is almost akin to a salaried crop – assurance of a fair and remunerative price (FRP) by the mills at the end of season is one of the most important reasons that growers opt for it. However, rising production costs now pose a challenge for growers as well. Prahlad Ingole, a farmer from Ardhapur taluka of Nanded taluka, says that for an acre of cane the costs of inputs come to almost around Rs 50,000 this year. “With increasing water stress it is becoming difficult for us to make our ends meet,” he says. Overall the situation for the sugar sector, the sweetness appears to be missing.