Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories

Against All Odds | A 40-day journey home: how Christopher Benninger’s partner gave him the gift of memories before time ran out

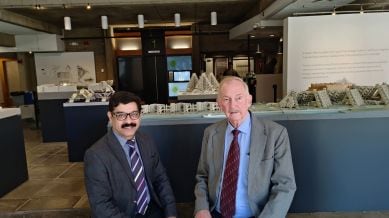

Ramprasad Akkisetti took Christopher Charles Benninger—an acclaimed architect who had left the US at 27 and spent the next 55 years building a life in India—on a trip to the US after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

In every human heart and mind, there lingers a longing—to return to spaces that shaped us. To walk down the lanes of childhood, to re-enter the doors we once exited in search of our dreams, to sit on the same grass where we dreamt of a distant future. The longing becomes more urgent as we age or when a cruel illness reminds us that time is running out.

It was a knock from the latter for Ramprasad Akkisetti, when on June 22, 2022, it was confirmed that his partner and companion, Christopher Charles Benninger—an acclaimed American architect who had left the United States at 27 and spent the next 55 years building a life in India—had prostate cancer. There were no visible symptoms, but the diagnosis was a silent earthquake. “I kept the news to myself for nearly a month, boiling inside, before finally telling Christopher in July. That day it was as if an atom bomb had dropped,” said Akkisetti.

Yet even as treatment began, Akkisetti shifted his energies from despair to doing something for Benninger that would fill his heart. Though the architect had never really voiced a desire to go back to his roots in the US, Akkisetti now read between the lines and realised some wishes have to be just understood. And he planned a trip.

“I shuffled all the work appointments and took 40 days off our work calendar from October to November 2022. Our journey was to begin in Boston and end in the small Florida town where Christopher was born on November 23, 1942. The trip was Christopher’s eightieth-birthday gift—though he did not know it until we were already in the air,” said Akkisetti, who told Benninger only a week before their departure, “Pack your bags. We’re going to America.” No itinerary. No explanation. Just the blind trust of a long-standing relationship.

As planned, they landed in Boston, the city where a young Benninger had studied architecture at Harvard and MIT in the swinging ’60s. Akisetti had arranged for Benninger to deliver lectures at both institutions. At MIT, Benninger stood before students half a century younger and spoke of drawings of the buildings around that he had made and pinned up as a nervous postgraduate. At Harvard, he led Akkisetti to a particular bench in Harvard Yard. “This is where I used to sit,” he said, palpably moved.

They visited 19 Quincy Street, the grand house where philosopher William James once lived and where Benninger had rented an upstairs room from 1966 to 1968. The current owner welcomed them warmly. Benninger recounted parties, famous visitors, and the high of youth spent there. Akkisetti watched his partner transform before his eyes—the stooped 80-year-old becoming, for fleeting moments, twenty-five again.

Because Benninger’s middle name was Charles—inherited from a beloved painter uncle—he had always joked about staying at the Charles Hotel. Akisetti booked it without hesitation, even at $480 a night. “Money we can earn again,” he said. “This experience we cannot.”

From Boston, they travelled to New York. The son of Benninger’s favourite childhood professor—Michael Jaleski, now a billionaire—insisted they stay in his Central Park penthouse. Michael had last seen Benninger when he was eight years old. Fifty-seven years later, he opened his home without hesitation. For a week, they lived 30 floors above the park, waking to the same treeline Benninger had once known through his aunt’s apartment that faced the United Nations— an apartment graced, in the guest room where young Benninger slept, by an original Picasso on the wall.

Akkisetti tapped on the contacts Benninger’s brilliant work as an architect had given them. The ambassador of Burundi to the United Nations, no less, secured them a private tour of the UN building. Benninger walked the corridors he had first entered as a 20-year-old and marvelled that not even the carpets had changed in 65 years.

From there, they moved to Washington, DC, and to Gainesville, Florida—the town Benninger had left in 1967, never to return for more than a brief visit. Benninger gave an impromptu talk to the wide-eyed teenagers of his high school. At the University of Florida’s architecture department, the president implored him to return and lecture again. The duo stood outside the three houses he had called home at different stages of boyhood and youth, the experience completely overwhelming both.

In a still-well-kept garden, Benninger reunited with his only surviving childhood friend—now 83—and together they stood beneath the orange tree the two little boys had planted seven decades earlier. The tree was laden with fruit that they plucked and ate, laughing like children.

Reunion with 102-year-old teacher, still sharp

They tracked down Benninger’s 102-year-old teacher, still alive, still sharp. A former classmate played guitar for him. Someone produced a dusty Christmas box Benninger had left behind in 1967—toys, letters, and relics untouched for sixty years.

And for 40 days, Akkisetti watched—as a partner, photographer, videographer, silent orchestrator of a film running on flashback. As Benninger walked around the Jackie Onassis Reservoir in Central Park, lost in memory, Akkisetti filmed him. He watched an 80-year-old man addressed, teasingly, as “my little boy” by a teacher twenty-one years his senior. Tears, laughter and silences filled with more meaning than words embraced them.

When they returned to India, something had shifted. Benninger—who had always written—began writing with renewed vigour and a sense of urgency. He completed the sequel to his famous Letters to a Young Architect. He started (but did not live to finish) a new book on civilisation and architecture. “Every day he spent six to eight hours at his desk, as if racing the clock he now knew was ticking,” said Akkisetti.

Benninger never openly discussed his cancer again, but the journey had done its work. The patchwork memories of a life split between two continents had been gathered and stitched together as one. He told Akkisetti he felt “complete”.

“I think the reason we yearn to go back to our roots is because no one can erase childhood from their lives-there is a kind of umbilical attachment to it. It’s also a precious memory we want to live again. Why else are alumni reunions so popular?” deduced Akkiseti.

Benninger died less than two years later. With all his chapters—Indian and American, the past and the present—closed.

“I think it was beautiful the way he ended his life, what more can I ask for a man I loved so dearly,” concludes the partner who gave him one of the best gifts anyone can—ta chance to relive life, before it ebbs away.

Click here to join Express Pune WhatsApp channel and get a curated list of our stories