Aishwarya Khosla is a journalist, currently serving as Deputy Copy Editor at The Indian Express. Her writings examine the interplay of culture, identity, and politics. She began her career at the Hindustan Times, where she covered books, theatre, culture, and the Punjabi diaspora. Her editorial expertise spans the Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Punjab and Online desks. She was the recipient of the The Nehru Fellowship in Politics and Elections, where she studied political campaigns, policy research, political strategy and communications for a year. She pens The Indian Express newsletter, Meanwhile, Back Home. Write to her at aishwaryakhosla.ak@gmail.com or aishwarya.khosla@indianexpress.com. You can follow her on Instagram: @ink_and_ideology, and X: @KhoslaAishwarya. ... Read More

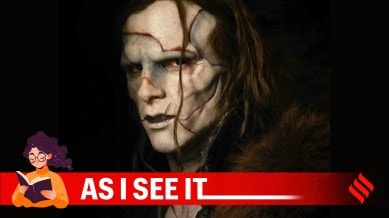

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is the perfect AI parable

If Shelley’s Frankenstein was a warning to the Enlightenment, del Toro’s is a lament for the Anthropocene

Two centuries after Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was born from a stormy Geneva summer, Guillermo del Toro has made the monster human again. His Netflix adaptation, starring Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi, has divided fans because it disobeys convention.

Del Toro’s creature is not a Shrek-like green-skinned brute jolted alive by lightning. He is, much to this bibliophile’s delight, a bruised, articulate soul stitched together from other people’s tragedies. The violence that defined previous adaptations has been replaced with sorrow and self-awareness. In the process, del Toro reminds us that reading Shelley’s novel merely as a horror story is reductive, she spun a tale of hubris and about creation without compassion.

And, the film has landed at the opportune moment of mankind’s history when we have created a slew of monsters that cannot be contained try as we might, the most recent of of those jinns that refuse to be bottled is artificial intelligence.

It is the perfect metaphor for this monster is also stitched together from the works of thousands of unwitting writers and artists, but even though it can talk and think, it remains a hollow phantom of a human being. It is made of human knowledge, but is processing it differently, sometimes lying and hallucinating and bypassing ethics. Shelley’s warning has turned out to be prophetic, if we cannot love what we make, it may yet turn on us. But, then many are swooning over artificial intelligence, so it is neither here nor there!

Elizabeth lives and speaks

Del Toro’s boldest act of resurrection is Elizabeth. Mia Goth’s Elizabeth is not the docile bride-to-be of Shelley’s novel, but an entomologist, a woman of science and conviction who sees through Victor’s arrogance. She is given her own philosophical voice, something women in Gothic fiction almost never had.

When she tells Victor that “war is what happens when ideas are pursued by force,” she could just as well be describing patriarchy itself. Shelley’s Elizabeth was silenced by the story’s end, but del Toro’s dies speaking truth to power. It is a rewrite that has drawn both praise and derision, some call it revisionism, others redemption. I am among those who approve of this adaptation.

Shelley, of course, would recognise this shift. Her original Frankenstein was written in the shadow of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, the great feminist philosopher. Shelley’s women were sacrificial victims of male ambition. Del Toro, more generous, offers one of them the gift of rebellion, and, finally, the right to be curious.

But, by turning Elizabeth into the Creature’s ally (even something like a kindred spirit), del Toro smooths out the moral jaggedness that made Shelley’s novel so haunting. In Shelley’s text, the Creature’s rage is born of rejection, but in del Toro’s, he is coddled by empathy (reminiscent to AI models) . The feminist message remains, but the fury is somewhat muted.

The monster for the age of machines

Del Toro shifts Shelley’s 1818 vision into the mid-19th century, amid the machinery of war and empire. His new character, Henrich Harlander, a syphilitic arms dealer bankrolling Victor’s experiment, is a stroke of contemporary satire. He is the 1850s answer to Silicon Valley, a man convinced he deserves eternal life simply because he can afford it.

It is easy to see del Toro’s Frankenstein as a parable for the AI moment. The hubris of men who build what they don’t understand, and the conviction that technology can conquer mortality. In Shelley’s day, that hubris was scientific. Today, dare I say, it is algorithmic. The question remains what happens when we create intelligence or life that outpaces our empathy?

In del Toro’s hands, even Victor’s relationship with the Creature becomes an allegory for toxic inheritance of the violence of fathers passed down to sons, creators to creations. His film is less about scientific sin than emotional neglect, It is the story of a parent who cannot love what he has made. This makes Frankenstein an elegy at heart. But, it also feels, fittingly, like an evolution of Shelley’s idea rather than a betrayal of it.

We were the monster all along

What makes del Toro’s Frankenstein so powerful , and so divisive, is that it refuses to punish the Creature or absolve Victor entirely. It sits in the uncomfortable truth Shelley left us that creators are always responsible for their creations, and that the line between monster and maker is perilously thin.

Shelley’s original novel ended with the Creature disappearing into the Arctic fog, a ghost of humanity’s guilt. Del Toro ends with forgiveness, or something like it. This is something viewers cannot forgive him for. But perhaps, after centuries of making the monster suffer for our sins, a little mercy is not misplaced.

If Shelley’s Frankenstein was a warning to the Enlightenment, del Toro’s is a lament for the Anthropocene (the period of time during which humanity has become a planetary force of change). In an era obsessed with progress, del Toro dares to suggest that what we need most is empathy. Or, to borrow Shelley’s own language, the courage to “tremble” at what we make.