In Gandhi and the Centrality of Ethics, KP Shankaran prepares the ground for a fresh understanding of Mahatma Gandhi

The essays trace the trajectory of Gandhi’s evolution as a philosopher

Anthropologist Verrier Elwin once sent MK Gandhi two extracts from Plotinus. Elwin was reading the Gita which reminded him of that third-century Hellenistic philosopher, who might pass off as an Advait Vedantin in the right translation. Gandhi replied that the passages were “very striking and very beautiful”, but one of them might not “appeal to the modern mind”.

What was wrong with the advice of “fashioning thine own image”? Mahadev Desai, who was with Gandhi in Yerwada then, was perplexed. Gandhi said the expression could give rise to hypocrisy. The analogy of sculpting was wrong too. “The soul cannot be carved out like that,” he said. His preferred expression for self-transformation was not ‘self-fashioning’, ‘self-formation’ and so on, but ‘self-purification’, atma-shuddhi – removing impurities from the self.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Pierre Hadot (1922-2010), the French philosopher who revived the concept of ‘philosophy as a way of life’ (it’s even abbreviated now: PWoL), did not know about Gandhi’s subtle distinction. He might have found it useful in his rejoinder to Michel Foucault. That rock star of continental philosophy, in his later years, was influenced by Hadot’s scrupulous readings of Greco-Roman philosophers, such as Stoics and others, who took philosophy to be not dry, conceptual debates but an active, engaged mode of living. Hadot clarified that Foucault in his studies of ‘the care of self’ was focusing on the self too much instead of the self in relation to the world.

Hadot, whom many describe as sagely, would have found in Gandhi a modern-day Socrates, the model philosopher whose life is based on exploring a set of values and beliefs, and whose philosophy derives from such a life. Hadot describes in great detail a series of ‘spiritual exercises’ mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman texts. Surprisingly, Gandhi practised many of them; some as improvisations, many as innovations.

Gandhi was indeed aware of the two ways of doing philosophy. He wrote to a correspondent in 1929, “You have specialised in theoretical philosophy, you must now specialise in applied philosophy.”

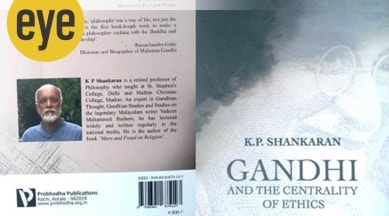

KP Shankaran, who taught Philosophy at Madras Christian College and St. Stephen’s College, has been working on this less-explored aspect of Gandhi – as a philosopher who “practised an ethics-led philosophical way of life”. His essays on this theme, many of which appeared in The Indian Express in recent years, have been published as a book, which also includes other related themes, notably essays on the Buddha and legendary Malayalam author Vaikom Muhammed Basheer.

The opening essay introduces Hadot’s notion of philosophy (which has become a major theme in western philosophy in the past decade), the second essay situates Gandhi in it and the third explores his practices.

For Hadot’s Greco-Roman masters, reading (‘anagnosis’ in Greek) was a spiritual exercise too, and in Gandhi we have someone who appreciated the potential – and, more importantly, limitations – of this practice better than most. In ‘Reading as a Sadhana’, Shankaran takes as the starting point a monograph, The Bibliography of Books Read by Mahatma Gandhi compiled by Kirit K. Bhavsar, Mark Lindley and Purnima Upadhyay. It lists about 4,500 titles for which textual evidence exists, such as Prison Diaries in which Gandhi gives astounding lists of books he read in jail. His reading was surprisingly eclectic; from Goethe’s Faust and Omar Khayyam’s The Rubaiyat in Edward FitzGerald’s translations to Patanjali and Bhartrihari, Plato and Suttanipata (ascribed to the Buddha).

“Constant reading, reflecting and writing, as well as political activism, helped Gandhi pose new questions to himself – engaging in self-transforming questioning was his idea of philosophy,” Shankaran writes. “This process, in turn, aided him in his unfinished journey from selfishness to moksha.”

This process also shows us Gandhi’s creative engagement with texts. For him, critical reading of a text meant testing it out in lived reality. Anasaktiyoga, his Gujarati translation of the Gita, is a lesson in how to read. For non-Gujarati readers, it was rendered in English by Mahadev Desai whose book-length preface prefigures the PWoL theme. Shankaran compares Anasaktiyoga with Plato’s The Apology: “Both these texts are equal, in their profundity, to some of the dialogues of the Buddha and of Jesus’s ‘Sermon on the Mount’. Apart from Gandhi and the Buddha, no other South Asian intellectual has ever done so much to enrich the ethical practices of mankind.”

Hadot organises two ancient lists of spiritual exercises with four themes: learning to live, learning to dialogue, learning how to read and learning to die. Socrates is the most obvious example of the last theme. So is, it turns out, Gandhi, with many similarities with the former.

Margaret Chatterjee and JTF Jordens have analysed how Gandhi synthesised his religion from diverse sources. Now that Akeel Bilgrami and Richard Sorabji have portrayed Gandhi as a full-fledged philosopher, Shankaran’s work prepares the ground for a similar overview of Gandhi’s evolution as one.

Ashish Mehta is a New Delhi-based journalist