Ambassador of Urdu, cherished in India and Pakistan alike, Gopi Chand Narang passes away at 91

His passing at his son’s residence in Charlotte, US, at 91, is a moment that the admirers and scholars of Urdu - a language that Narang so loved, taught and critically analysed - will lament for decades to come

In one of his conversations about his close friend and eminent Urdu scholar Gopi Chand Narang, writer-filmmaker Gulzar had once said: “Do pao pe behta dariya, ek pao pe thehri jheel/ Jheel ki naabhi par rakhi hai Urdu ki roshan taqdeer… Dr Gopi Chand Narang (A river flowing on two feet, a lake resting on one leg, and on the lake’s umbilicus lies the illuminated destiny of Urdu…)”.

Foremost Urdu scholar, linguist, literary critic, erudite litterateur, former Chairperson of Sahitya Akademi, and an authority on Urdu, Gopi Chand Narang’s passing at his son’s residence in Charlotte, US, at 91, is a moment that the admirers and scholars of Urdu – a language that Narang so loved, taught and critically analysed – will lament for decades to come.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

One of its most nurturing keepers and propagators, Narang not only traced the origins of the language but told off many who tried to broadcast the idea that Urdu had come to the Subcontinent from the Arab or the Persian world. He called Hindi and Urdu as “two sides of the same coin, as their grammar is the same”. He highlighted that Urdu is neither from Farsi nor is it Semitic and that both Hindi and Urdu are based on khadi boli. “Zubaan ka mazhab nahi hota, zubaan ka sama hota hai, uske bolne wale hote hain. Urdu bolne walo ka mila jula samaj hai. (Language does not have a religion, language has a time and people who speak it. The Urdu speaking population is mixed).”

While one of his most prominent works Urdu Ghazal aur Hindustani Zehn-o Tahzeeb ( Urdu Ghazal and Indian Mind and Culture) traced the origins of Urdu ghazal, underlining how it was not just a piece of love poetry, but that the genre comprised intellectual and cultural viewpoints of both Hindus and Muslims, it was one of his earliest works — Urdu Readings in Literary Urdu Prose (1968) that got much attention all over the world. Even today, wherever Urdu is read and taught in the world, the book is likely to be in the curriculum.

He extensively worked on explaining and analysing the works of Ghalib, Mir Taqi Mir and later more progressive poets such as Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Firaq Gorakhpuri among others, and penned about 60 books. Apart from these, there were 10 books designed for children under the title ‘Let’s Learn Urdu’ in English and Hindi. His extremely well-researched studies make up the books Hindustani Qisson se Makhooz Urdu Masnaviyan (1961), and Hindustan ki Tehreek-e-Azadi aur Urdu Shairi (2003) are lessons in social and cultural studies.

A keen reader of world literature, his frame of reference was expansive and almost encyclopedic at times, especially when he spoke of modern and post-modern literature.

Born in Dukki, a sleepy little village in Balochistan, Narang was introduced to literature by his father, who was a scholar of various languages including Baluchi, Pashto, Sanskrit and Persian. Narang moved to Delhi’s Karol Bagh after the Partition and tried to survive with some small jobs in the vicinity.

After some time, he joined the Masters in Urdu programme at Delhi University under Professor Khwaja Ahmad Farooqi. Soon, he received a research fellowship from the Ministry of Education to complete his PhD. This is when Narang received guidance from noted names such as Dr Zakir Husain (who later became the President of India), Dr Tara Chand, and Dr Syed Abid Husain, among others. He began his teaching career in 1958 at St Stephen’s College.

Since PM Jawaharlal Nehru was keen on having a proper Urdu department in the University, Narang (along with Farooqi) had presented the proposal to Nehru. The department was set up in 1959 and Narang moved there and became a reader in 1961. He then taught at the University of Wisconsin but longed to return after two years. His neighbour and scientist Hargobind Khorana asked him to not leave, citing how Khorana himself wasn’t going to get a lectureship in Ludhiana while this country (the US) had made him a Nobel Laureate. Narang told Khorana that “your laboratory is in the US, mine is back home.” He soon returned to be among the people who spoke of and in the language he so adored.

One of the consequences of Narang’s love for Urdu was that he was one of the few writers cherished unequivocally in India and Pakistan, recognised by both their governments (he received Padma Bhushan in India and Sitara-i-Imtiaz (Star of Excellence) in Pakistan). It’s often said in Urdu literature circles that people from Pakistan who live all over the world may not know the name of their Prime Minister, but they would always know Gopi Chand Narang. In the 80s, amid Zia-ul-Haq’s reign and martial law, where all content on radio and TV was monitored strictly, Narang was the only Indian whose interview took place at PTV headquarters and was relayed on TV.

Intezar Hussain, the leading literary figure from Pakistan, would say about Narang that when he stood on a stage in Pakistan and spoke, it felt as if he was the representative of the people of two countries, never only the one where he resided. Each time Urdu was politicised, Narang spoke up. He pointed out that Urdu is the language of liberalism, of progression, of love. “Ye Hindu aur Musalaman ke darmiyaan raabte ka pul banaati hai (It builds a bridge of communication and connection between Hindus and Muslims),” he’d say.

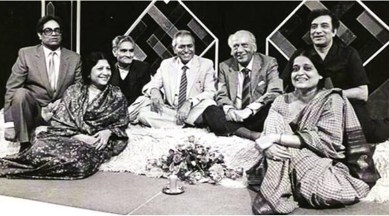

Narang can also be credited for making sure that author Amrita Pritam was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, the country’s highest honour in literature, making her the first woman to win the award. Narang was the Chairperson of the Akademi and went to give this award along with his close friend Gulzar at her Hauz Khas residence. Her partner Imroz tried to show the award to her while she lay in bed, not recognising anyone. Imroz told her, “Aye lye ke aaye ne tussa de vaaste (They have brought this for you)”. Imroz told Narang that she would have appreciated it earlier. Narang said that he wanted to make sure that she was awarded in her lifetime.

Narang, who remained synonymous with Urdu and its most ardent guardian till the end, also stood for the very imperative message of unity and solidarity. One wonders that if every language in the country found a Gopi Chand Narang to understand it, to steer it, their fates would be very different. Urdu will remain indebted to Narang for his endless devotion to it, and for plumbing the depths of its soul for the world to savour the adab (literature), its complexity, and, most importantly its heart.

📣 For more lifestyle news, follow us on Instagram | Twitter | Facebook and don’t miss out on the latest updates!