Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Kashmir’s syncretic culture is the writing on wall – exhibition documents written text on public buildings, down centuries

The Srinagar-based architecture historian has been the design director for INTACH in Kashmir and has written several books on the syncretic traditions of the region.

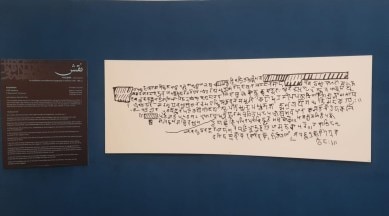

Kashmir, which sits on the crossroads of civilisations, has had Buddhists, Persians, Sikhs and Mughals influence its craft and culture. Deeply embedded within the snow-clad mountains and green valleys is a spiritual way of life that manifests in the way people make declarations on mosques, shrines, bridges, monuments, temples and gardens. At the India International Centre art gallery, an exhibition is being held that showcases these testimonies. Called ‘Architectural Epigraphy in Kashmir’, these writings on walls and entrances of buildings capture the mood of the society from the 14th to 19th century.

Why should it matter though, asks curator Hakim Sameer Hamdani. “Epigraphy can be compared to what modern billboards do. They are in your field of vision and are meant to be seen, read and understood. The messaging could be devotional, commemorative, often led by the community as a tribute to a place or person. While there is a devotional aspect, it is also a literary and aesthetic moment, defining the culture of the space,” he says.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

The Srinagar-based architecture historian has been the design director for INTACH in Kashmir and has written several books on the syncretic traditions of the region. The exhibition is the product of a research grant from The Barakat Trust in London that enabled Hamdani and team to visit over 600 public buildings and document 41 of them.

An exhibit that presents the confluence of ideas from the region is the ‘hānkal’. Made from metal or glass, this is a medallion clasped by three strings of chains on two sides. Usually found at the threshold of a shrine (never a mosque), it is emblematic of the temple bell that believers touch before entering the sacred space. With verses from the Quran or the lines from a saint, it is a call to repentance and a reminder to hold on to the faith.

The weaving of architecture, craft and art of calligraphy also emerges in this exhibition, where we see patterns of the Kashmiri shawl through colours and motifs, both outside and within buildings. For instance, at the Khanqah-e-Molla or Shah-e-Hamdan, one of the oldest Muslim shrines on the banks of the river Jhelum, there are eight doors to the left and the right of the structure. Each door has designs and patterns inspired by these shawls, which were a rage in the 19th century across the world. It is also telling about Sufi saint Mir Syed Ali Hamdan, who was a patron of art and craft in Kashmir. The shrine that has seen multiple renovations due to fires, also testifies to the shift in building materials, from stone in the early 15th century mosques to wood.

The syncretic nature of the region also presents itself in the text on temples, built during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh around the early 19th century. “While the inscription is calligraphic, the language is Persian. The text is not in Gurmukhi, if you notice. It’s an ode to Ram and Shiva and Guru Nanak. Ranjit Singh imitated and mimicked the regalia of the Mughal courts, and it shows in the way he chose to express himself,” says Hamdani.

At the turn of the 20th century, Kashmir’s linguistic landscape saw a transformation. Persian gave way to Urdu and Kashmiri, and later, Hindi. And over time, calligraphy got left behind for formal, concise inscriptions. For Hamdani, it has also meant a relook at how we see the past to understand our present. While renovations and newer buildings erase the beauty and aesthetic of history, he accepts that change is inherent to life itself. “Most of these buildings today are community owned, and the community exerts its ownership on them. It may sometimes end in results that are not aesthetically favourable, but then you can’t take away agency from the community. Unlike in the West, where heritage is rather straight jacketed, you can’t change a window or door, here we live with our monuments. And change is inherent to preservation and conservation,” says Hamdani.

The exhibition closes on September 28.