Fali S Nariman, who died today at the age of 95, once asked me to forward to him a particular passage from Hamlet. There, the Prince of Denmark asks Polonius to take good care of the actors in his play. The passage reads, “… Do you hear, let them be well used, for they are the abstract and brief chronicles of the time; after your death you were better have a bad epitaph than their ill report while you live.”

Today, as a bit player in his long life and magnificent achievements, I can only offer an abstract and brief chronicle of my interactions with him.

To call him the Bhishma Pitamah of the Indian legal world would be a cliche, but that certainly was the position he occupied, even on his final bed of arrows. He had written in his autobiography, “I have lived and flourished in a secular India. In the fullness of time if God wills, I would also like to die in a secular India.” He was extremely worried about the direction that India was taking. He thought that India was drifting to being a theocratic state.

He was a world-class lawyer to whom everybody deferred. Among his friends and contemporaries were the top legal minds of the world, but from prime ministers to peons, everyone looked to him and up to him.

Nariman occupied the moral centre of the Indian legal world, perhaps ever since he resigned from his position as the Additional Solicitor General the day the Emergency was declared. He was a man who knew what was right and what was wrong, and he did not compromise on his moral view. For example, years later, when there were attacks on Christians in Gujarat, around the time that he was representing the state government in the Narmada rehabilitation case, Nariman withdrew from the brief in protest.

He had a deep and abiding respect for the law, and his arguments were always very carefully crafted. He would convey an argument in such vivid imagery that it would strike an immediate chord with the judges. A relatively small case that I happened to witness illustrates his craft as a lawyer. The case was related to a sacred Parsi well near Churchgate station in Mumbai. The municipal corporation proposed to build a public urinal near the well. Nariman appeared in a PIL asking for the urinal to be built somewhere else. He stood up before the Bench and told them that in India, the problem is not that we go to the toilet, it’s that we go near the toilet. Not only was that a clever way to put it, but the imagery in his argument was such that those lines summed up the case.

Then there was the occasion when perjury proceedings were directed by the Karnataka High Court against the chief secretary of state in the Bangalore Mysore Expressway project. An urgent special leave petition had been filed. I was the Advocate on Record for Karnataka and Nariman was the Senior Advocate. The day before the petition had to be filed, he and I had a little bit of a row in another unconnected matter. On the opposite side was a galaxy of lawyers, including Dushyant Dave and Mukul Rohatgi. Nariman had castigated us during the conferences and we were very shaky about what would happen when we went into court. But then, before a Bench comprising Justice Ramesh Chandra Lahoti and Justice Santosh Hegde, who was due to retire the same day, he got up and told the court that he did not think senior advocates were required to mention the matter. Justice Lahoti asked him, “What is your suggestion, Mr Nariman?”, to which he said, “Mr Sanjay Hegde is here, he’s a good lawyer and you should hear him.” With that one line, he made up to me and he knocked out the senior advocates on the other side. And no sooner did I get up to say that this was the chief secretary’s matter, that Justice Lahoti said that the Bench would consider the matter and he granted us a stay. The point of this episode is not the gratitude that I owe Narmian — it’s that he could come up with both a strategy and an argument that nobody could have envisioned.

He was a fountain of knowledge that enriched anybody who worked with him on any matter. His long-standing junior, Subhash Sharma, came to him under some bar association programme where juniors without a legal background were placed with seniors. Sharma came from Jammu and was then not very fluent in English. He joined Nariman in the mid-1980s when the Bhopal Gas case was going on and has stayed with him till today as a junior and almost as a foster son. He was Nariman’s Sancho Panza and Boswell. While he learnt Nariman’s requirements, he also knew how to handle his temperament and may even have taught him as much Hindi as Nariman taught him law.

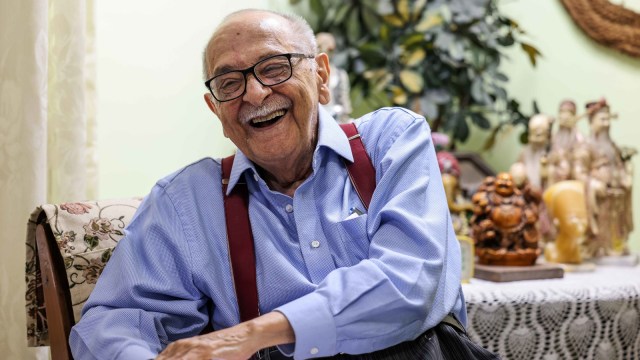

Till the very end, his mind remained sharp and active. I am told that as late as 10 pm last night, he was working on a case. I last met him in April 2023, by which time his wife, Bapsi Nariman, with whom he shared over 60 years of partnership, had died. But Nariman was full of life, and we had a great evening together. He leaves behind his son Rohinton, who has had a storied career in law and daughter Anaheeta. He has gone in the fullness of time, but his legacy will continue to illuminate the paths of several men and women of law who will come after him.

The writer is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India