The Supreme Court has decided in favour of the Government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi on the issue of who controls the bureaucracy in the country’s capital. While we may not have heard the last of this dispute, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s frequent run-ins with the Union government is not without precedent either. In fact, Delhi has a long history of such quarrels — even when the same party has held the reins in both places.

The classic case is that of the first Assembly that was constituted in 1952 with Chaudhary Brahm Perkash as the first chief minister. It was a clash that ended with Perkash’s resignation, followed soon after by the abolition of the Delhi Assembly.

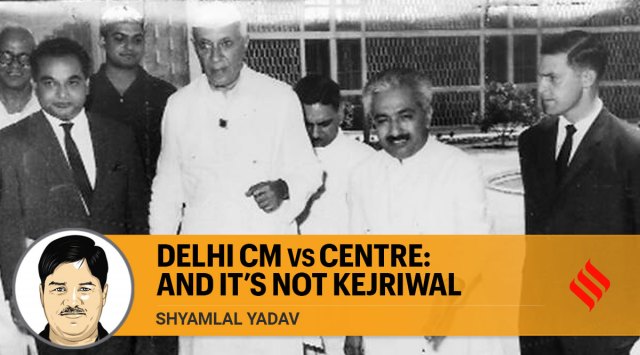

In the first Assembly, there were 42 seats, including six double-member seats. When the results came out, 39 seats were won by the Congress, five by the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (erstwhile BJP), and two by Socialist Party, among others. When it was time to pick a chief minister, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru went with Nangloi MLA Brahm Perkash, a 33-year-old Yadav farmer and then president of the Delhi Pradesh Congress Committee, ignoring the claims of stalwart and Chandni Chowk MLA Dr Yudhvir Singh. Brahm Perkash took oath as the first chief minister of Delhi on March 17, 1952.

Those days, Delhi was one of the 10 part-C states (along with Ajmer, Bhopal, Bilaspur, Coorg, Himachal Pradesh, Kutch, Manipur, Tripura and Vindhya Pradesh) and, like today, had limited power with no control over land and law and order. In place of the L-G, these part-C states had the Chief Commissioner as the Centre’s representative.

While Kejriwal’s tussle with the Centre started on Day 1, in Brahm Perkash’s case, it was a smooth start.

In an interview that he gave to the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML), decades after he was removed as CM, Brahm Perkash had said, “(After taking oath) I met Nehru ji. Then Dr Katju (Home Minister Kailash Nath Katju) called me. Chief Commissioner Shankar Prasad was also sitting there. He told me that if there is anything that’s complicated, I can discuss it with him before writing notes on the file. He said he would take me through the pros and cons of those issues.” (The interview to NMML has been incorporated in the book Dilli Ke Pratham Mukhyamantri Chaudhary Brahm Perkash, published by S Chand and Company.)

But soon, things started to sour, particularly after a new Chief Commissioner, A D (Anand Dattahaya) Pandit, took over in 1954.

Brahm Perkash says, “He (Chief Commissioner Pandit) wanted to interfere in every matter… Once he ordered the demolition of 700 jhuggies though it had been decided that these would not be demolished. He sent orders directly to the Chairman of Improvement Trust (DDA’s precursor). I immediately conveyed to the Secretary that I was going to stop the demolition and he should tell the Chief Commissioner to send the police to arrest the Chief Minister… The Chief Commissioner harassed me a lot and he kept doing so till the end. He did not like any elected representative.”

Perkash went on to say, “Everybody thinks Delhi is his fiefdom. I showed these officers their place. I neither insulted them, nor did I allow them to do things on their own… I worked in a way that no officer of the Union government could interfere in Delhi’s matters… My will power was strong.”

What aggravated Brahm Perkash’s fight with the Centre was his politically ambitious plan to create a Greater Delhi state comprising Delhi and certain parts of Western UP, Punjab (Haryana was not created then) and Rajasthan.

As Perkash said, “This was opposed by the UP leadership, particularly Govind Ballabh Pant (former UP CM who replaced Dr Katju as Union Home Minister).

The Hindus of Punjab were afraid…This (idea of Maha Dilli) was not liked by our leaders. Perhaps Panditji (Nehru) also did not like it… Politically, I had to pay a huge price for that. Perhaps that was also one reason that Delhi’s statehood was lost.”

Things got worse for Brahm Perkash. “The Chief Commissioner was against me. G B Pant wanted to corner me because I debated things firmly with him. He tried to find something against me and all my files were inspected but there was not a single file with which he could grill me.”

The PM too was not on his side. “Pandit Nehru was initially with me openly. But when the quarrel started, he pulled himself from Delhi matters and became neutral, leaving me on my own,” he said.

Finally, on February 12, 1955, Brahm Perkash resigned as CM and Daryaganj MLA Gurumukh Nihal Singh was sworn in his place.

A disappointed Perkash says in the interview, “Our dream was to make a Greater Delhi but that dream ended. Today we are paying its cost. Delhi has no land but its population has increased.”

Brahm Perkash, who went on to be Lok Sabha MP from different seats of Delhi, later quit the Congress and was Minister of Agriculture in Chaudhary Charan Singh’s short-lived Central government in 1979.

The States Reorganisation Commission under Fazl Ali stated in its report that was submitted in 1955: “The future of Delhi has to be determined primarily by the important consideration that it is the seat of the Union Government…This peculiar diarchical structure represents an attempt to reconcile Central control over the federal capital with autonomy at State level. It is not surprising that these arrangements have not worked smoothly… It is contended that the development of the capital is hampered by the division of responsibility between the Centre and the State Government and that there has been a marked deterioration of administrative standards in Delhi.”

The Commission recommended that “a separate state government” for Delhi was no longer required. On November 1, 1956, Nihal Singh resigned as CM and the Assembly was abolished. However, Delhi’s leaders continued to demand statehood and in 1991, the Union government headed by PV Narasihma Rao granted Delhi its Assembly again. Elections to the new Assembly were held in November 1993. But Brahm Perkash was not around to witness the restoration of the Assembly. He died on August 11, 1993.

However, successive governments continued to raise the demand for full statehood for Delhi, more so when Delhi and the Union government were headed by different parties.